2023-06-12 19:43:33

«We celebrate this afternoon a unique cultural event. For the first time in history, a great nation has allowed one of its national monuments – an unbroken Romanesque apse, built almost 800 years ago by pious artisans from Fuentidueña – to be transported across the Atlantic as a free and generous loan to the people of the United States. Joined”. With these words, the president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (MET), Roland L. Redmond, inaugurated in 1961 the reconstruction of the apse of San Martin de Fuentiduena who had traveled from Segovia to The Cloistersthe medieval art section of the museum.

At the MET they had reason to congratulate themselves. The Romanesque complex had been in their sights for thirty years and they had finally achieved what seemed impossible: that a national monument, so declared since 1931, would leave Spain. “It is something inconceivable”, underlines the professor of History of Architecture Jose Miguel Merino de Cáceres. And yet, it was carried out with the acquiescence of the Franco regime, the San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts (RABASF) and the Royal Academy of History (RAH), as well as notable representatives of the cultural elite. and social situation of the moment, as has been documented by Merino and Maria Jose Martinezprofessor of Art History at the University of Valladolid, in her book ‘From Fuentidueña to Manhattan‘ (Lecture).

It is “consented dispossession”as the authors of this rigorous investigation prefer to call it, given what they consider to be an abuse of the term ‘plunder’, was sold in 1958 as “a temporary assignment”, albeit for an indefinite period, accepted by the Spanish authorities in exchange for the six wall paintings of San Baudelio de Berlanga (Soria) that today are exhibited in the Museo del Prado.

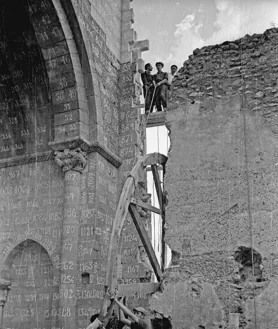

Alejandro Ferrant was in charge of effectively dismantling the apse. 3,396 ashlars and various pieces were counted that were packed in 839 boxes heading to the United States

This is how the news spread in the newspapers of the time, which highlighted the arrival of the paintings in headlines, relegating to the background the departure of some “ruins in very poor condition”, without mentioning that it was a national monument. «The information was measured to the millimeter», says Martinez. The resolution was not published in the Official State Gazette and it was not announced until the 839 boxes with 3,396 ashlars and pieces that the freighter ‘Monte Navajo’ transported arrived in New York.

The researchers, authors in 2012 of ‘The destruction of Spanish artistic heritage. WR Hearst: “the great hoarder”‘ (Chair), have discovered in unpublished letters and documents what the MET tried to acquire the apse of Fuentidueña in the 1930s and he resumed his initiative after the forced hiatus of the Civil War and World War II.

The director of The Cloisters James J. Rorimer, who was a member of the ‘Monuments Man’, saw in the 50s the opportune moment to get that great monumental construction that he longed for. The Franco dictatorship was trying to break out of isolation and there was a new climate of bilateral relations between Spain and the US, which took shape in the Madrid Pacts (1953) and in “certain permissiveness” with North American collectors and dealers, according to the researchers. “They used heritage as one more piece on the board of diplomatic relations,” they point out while recalling the movie ‘Welcome, Mister Marshall’ that reflects so well the Spanish society of those years. «Villar del Río could have been Fuentidueña, perfectly».

Merino and Martínez have documented the entire process that crystallized in the export of the apse: from the contacts with the antiquarian Raymond Ruiz to negotiate the purchase with the Bishopric of Segovia and the Fuentidueña City Council, up to Rorimer’s communications with the US embassy in Madrid or with various ministers. “The idea of the exchange came much later, as an emergency exit”, relates the art historian. In fact, the MET acquired the paintings of San Baudelio when the deal was approved, to send them to Spain. “They were in the market. If Spain had wanted to, it could have bought them without parting with anything, ”says Martínez. Later the MET would obtain others from the same Soriano group, by the same vendors, as a donation. Which are now also on display at The Cloisters.

you critics

In order to authorize the exit of the apse, the agreement had to be supported by the royal academies, where the debates were “very tense”, according to what the researchers have found out. At the San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts, the decision was made by majority, not unanimously. Of the 28 academics who attended the session, 19 voted in favor, but seven against, and there were two abstentions. There was also a particularly critical voice, that of César Cort y Botí, who issued a private vote in which he stated that it was a secret sale because there had been payments disguised as donations.

Also Leopoldo Torres Barbas voted against in the Royal Academy of History. In a letter that he sent to a colleague, he explained that after having fought for the conservation of Spanish monuments and having protested against the emigration of others to the United States, agreeing to the transfer of the church from Fuentidueña would have been to renounce all his life.

Luis Felipe de Penalosa, president of the Provincial Commission of Monuments of Segovia and uncle of José Miguel Merino, strongly opposed this operation, of which the members of the corporation he represented were not informed. In the book they collect letters in which he harshly criticized the departure of the monument and the position of the royal academies. «Critical voices slept in the archives. They fell silent. Everything was silenced, ”says Martínez.

A daughter on the board

The support of the RABASF and the RAH included the favorable reports from Francisco Javier Sánchez Cantón, deputy director of the Prado Museum, and above all from the archaeologist and historian Manuel Gomez-Moreno, an authority at the time with an Achilles heel, his daughter Carmen, as Rorimer discovered. The book publishes letters from the young woman after meeting the director of the MET and after he offered her a job at the museum. She also Rorimer’s letter, with very elegant and polite forms, in which she pressured Gómez-Moreno in this regard. “We have been able to document a suspicion that was in the air,” says the specialist in heritage, collecting and the art market. “It was not known that Don Manuel Gómez-Moreno was the one who had encouraged the transfer, for favoring the daughter,” adds Merino.

Carmen Gómez-Moreno, who was later in charge of moving the apse and who developed her professional career at the MET, argued then, like so many others, that the monument would end up disappearing in Spain, while in the United States it would receive the attention it deserved. deserved. «This thesis always came up, but who knows! The monastery of Santa María la Real, in Aguilar de Campoo (Palencia) was an absolute ruin and today it is an institute and the headquarters of the Santa María la Real Foundation- Center for Romanesque Studies», Martinez replies.

#true #story #national #monument #Spain #brick #brick