2023-06-18 07:01:00

Just by mentioning it, Alba’s friendly face* is assailed by rage and indignation. He is invaded by rancor that only manages to give birth to impunity. She can’t find how to accommodate her square brown hands. He moves her restless fingers when remembering that morning of March 28, 2022, when an Army operation silenced the lives of 11 people in the Alto Remanso village of Puerto Leguízamo, in Putumayo. Sobs are enough for her to go from fury to grief and from anger to tears.

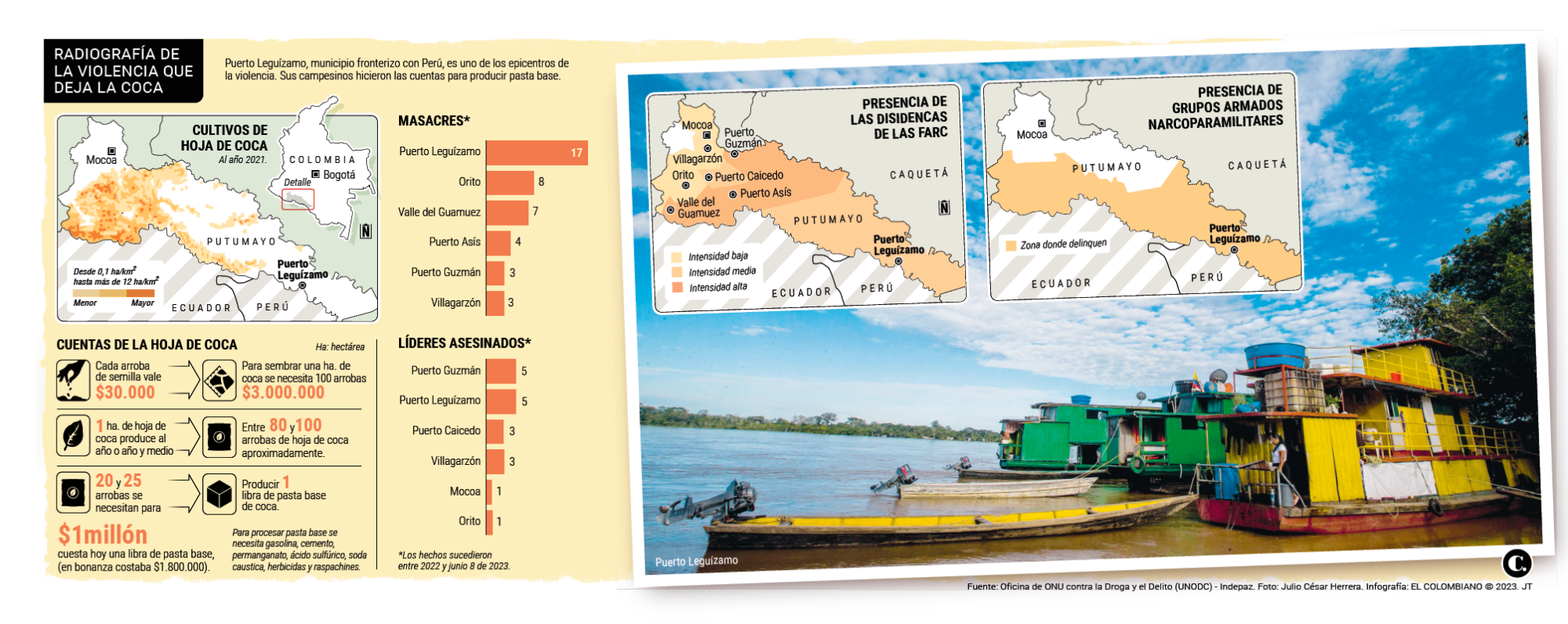

The one in Remanso was one of the 10 massacres that shook the department between 2022 and so far in 2023 –leaving 42 dead–, a drama that adds to the crimes of 18 social leaders. Less than 15 days ago, on June 6, another massacre mourned the region, this time in Villagarzón, located an hour and a half from Puerto Asís by road. (See infographic at the end).

In Puerto Leguízamo, Alba agrees to speak – as if perhaps she hadn’t already shouted – but she sets one condition: that her identity not be revealed. “Things are still very delicate,” she warns, wanting to explain the price of raising her voice. More than a year has passed and there are no answers or justice, only the same desk apologies that Alba does not stop feeling as fleeting as icy.

He is passing through the urban area of the town, at his mother-in-law’s house. Here you will spend the night, since reaching Alto Remanso can take up to two hours aboard a canoe that does not have a direct route, but on the way to Puerto Asís it has a stop in its territory. The journey is still risky, so he prefers to stay to watch the sunset of a gray and humid afternoon –of those that are suffered in Putumayo–. He attends us on the outskirts of the house, in a sidewalk located 20 minutes from the central park. He asks that the name not be mentioned.

Finally, he sits down in search of balance and passivity, and – while two dogs bark incessantly – he is encouraged to narrate the ravages of violence in Puerto Leguízamo, the largest municipality in the department. As big as her woes. She – who almost forcibly took over as an indigenous authority as a way of honoring her dead – speaks of the massacre with fear and anger, but with a hint of disbelief and astonishment. Centimeters from her is her mother-in-law, who is silent, while she holds a downcast look.

Both still do not understand how a Public Force operation – “which is supposed to take care of one” – ended up exacerbating the violence and contributing to the horror of the conflict while they shared in a bazaar to collect money. Among the dead, for which 25 soldiers will be accused, were his mother-in-law, two friends and some acquaintances. “My fabric,” he says, referring to the ancestry of his family.

He claims that they wanted to strip the dead of their peasant and indigenous role to pass them off as armed, as subversive, as violent. “Which is it? It is not known. This is flooded with guerrillas and paramilitaries, and one is left in the middle ”, reproaches Alba while her hands remain restless.

The extension of Puerto Leguízamo –with an area equivalent to almost 30 times Medellín or 10 times Bogotá– allows armed groups of all stripes to roam freely. And it is that, either because of the dissidents of the Central General Staff, the Second Marquetalia, the Border Commandos –a symbiosis between the Farc and the Self-Defense Forces– and now even the Public Force, the almost 20,000 inhabitants of Puerto Leguízamo live in incessant violence in which are victims, cannon fodder and even perpetrators. Yes, perpetrators, because “children continue to be recruited,” Doña Carmela *, Alba’s mother-in-law, manages to say, as she breaks the silence and unloads words.

One of the groups that is present in the region is the Carolina Ramírez front of the dissidents of the General Staff, under the command of alias “Danilo Alvizu”. With close to 250 men under arms, they are responsible not only for clashes with the Border Commandos, but they were the ones who gunned down 4 indigenous minors who were victims of recruitment, which caused the Government to suspend the bilateral ceasefire last May in 4 departments, including Putumayo.

In the case of Puerto Leguízamo –categorized as one of the 170 PDET municipalities in the country, that is, the ones most affected by the conflict and mired in poverty–, the perplexity grows if one considers that in the heart of the urban area, meters from the central square and a few steps from the pier where the market arrives, stands an imposing naval base of the Navy that, far from conveying security, continues to cause suspicion among the inhabitants.

A peasant who arrives at the pier speaks angrily about the “piranhas”, as they are known for some imposing and aggressive black boats used by the Navy to combat drug trafficking, which now extends to Peru, just an hour away. . “They go full shit and sink our rafts, damaging the food and fish that one brings. If I had a weapon, I wouldn’t let it ”, he assures, evidencing how the violence has disrupted them and any setback is a reason for conflict.

the genesis

The seed of this violence in Putumayo is the very fertilizer of its development: coca. One is a consequence of the other and the bid to take over drug trafficking routes, to equate more and more cultivated areas and to have a livelihood exacerbates the blood. But not even that gives peasants and indigenous people a living. And not because the business is not lucrative, but because there is no one to buy it anymore.

It is a reality to which everyone gives their explanation in Leguízamo, even though the phenomenon is repeated in Nariño, Cauca or Norte de Santander. However, it has its particularities in Putumayo, where – adding Caquetá – the United Nations calculates that 16% of the area planted with coca crops is concentrated. Punctually 31,874 hectares of temporary progress, 45% more compared to 2020.

An example of how ephemeral this development can be is portrayed with nostalgia by Humberto*, a 56-year-old farmer who converses in a hoarse voice and who wears a Colombian National Team shirt a few steps from the town square, where in the distance see an imposing monument that the Army built in 2019 as a tribute to its fallen heroes: 3 stone men are erected as a statue who, even in the midst of adversity and onslaught, try to keep the Colombian flag standing. Emulating that effort, Humberto now tries to bring a plate of food to his house in the midst of the biggest coca crisis the region has experienced.

We’ve been like this since November. Nobody buys anymore. Coca is repressed—he explains, anticipating the reason for the recession that he does not hesitate to classify as the main line of the region’s economy. —With the operatives and the heavy hand, Petro has stopped the ‘duros’ and they no longer buy from us. There is also overproduction and that lowers the price,” concludes Humberto with a gasp of resignation, who, like countless peasants, got into debt looking for the “cocalero dream” and now lives firsthand an economic maxim: the law of supply and demand.

With President Gustavo Petro, who has a mural on a street near the port where the market arrives very early, they have a duality: “They no longer persecute the peasant who grows coca leaves, that has been a relief. But they have screwed us because there is no one to buy anymore”, says Jose*, who arrives at the dock to unload the market in search of some money.

“The December that we lived here was the most bitter. There was no money, nothing could be bought. We are screwed, ”he adds, as he walks to his house, built with wood and entrenched on a sidewalk 20 minutes from the town center. It has a pale blue facade and a dirt floor. While José complains, his son plays with a dirty and battered ball in a corner of the house.

Even Sonia – the only one who dares to give her real name for this report, although her last name is reserved – assures that commerce is paralyzed, that there is no longer anyone to fill her canteen and that buying a beer is a luxury, so the indigenous people prefer “coroto”, a transparent and cheap liquor that comes from Brazil: “With a small bottle of that they are enough. That is why you see some who end up sleeping on the street, ”she explains with a hint of complaint, because no matter how hard the situation is for some, the drink cannot be missing.

Juan* one of the few “monkeys” in the town –in Leguízamo it is easy to distinguish the foreigner, everyone knows each other and has their indigenous traits–, maintains optimism while he attends to a supply store, now empty because, as coca falls , the sale of everything that makes possible that cocktail that is the base paste also decreases. “What has screwed up this is that gringo drug,” he says, referring to fentanyl, a synthetic drug that is dangerous as well as addictive.

Fentanyl – of which there are already timid, but increasingly alarming records in Colombia – is made in chemical laboratories and its process is not as complicated as that of cocaine. “It doesn’t addict them, it kills them,” adds Juan as he dusts off his store. To measure the lethality of fentanyl, it is enough to say that in 2022 alone in the United States it killed 100,000 people.

However, the coca business is still going strong and is far from over. An example of this are the tentacles that continue to come out of the animal. A little less than an hour in a canoe equipped with a small motor is enough to get from Puerto Leguízamo to Soplín Vargas, a Peruvian town where farmers now go to plant coca leaves.

The reason?: “Here nobody persecutes us. Up to here the armed forces do not get involved, nor does the Colombian Army have jurisdiction. Even the Peruvians have put us in competition because the business is growing and their authorities are more vigilant. It’s time to be alert,” says Efraín, a 52-year-old peasant who protects himself with an increasingly frayed hat, who offers to take us in the middle of the search that continues to prevail at the border.

When he barely had a little more than two months in office and enjoyed the honey of approval, Petro visited Puerto Leguízamo, where more than half of the population supported him in elections (53.5%). From there he launched a lifeline to confront the use of illicit crops: replace it with programs to protect the forest. However, people are still waiting. “If he manages to protect us, do justice and offer something other than coca, that’s enough,” says Alba, who finally manages to intertwine her hands.

*Names changed

at the request of the sources.

#live #repressed #coca #unleashed #violence