In the official biography of Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov it is said that in 1957 his name was proposed as a potential talent to be hired at Harvard University. However, a professor from the Slavic Studies department would have replied: “even assuming that he is an important writer, what will we do then, will we invite an elephant to fill the chair of zoology?”.

Nabokov was never called to Harvard and in 1958, following the astonishing success of Lolita (and the consequent economic return), “the elephant” completely abandoned teaching. However, the Russian writer cultivated for a long time the project of collecting and organizing notes, diagrams and university lectures in one volume, which unfortunately he could not complete. The lessons, in fact, were conceived for oral presentation; moreover, the enormous amount of material and Nabokov’s stylistic meticulousness certainly represented major obstacles when revising for a publication. Despite this, after the writer’s death, Fredson Bowers – with the invaluable help of Dmitri and Vera Nabokov, Vladimir’s son and wife respectively – managed to complete the ambitious project in 1980.

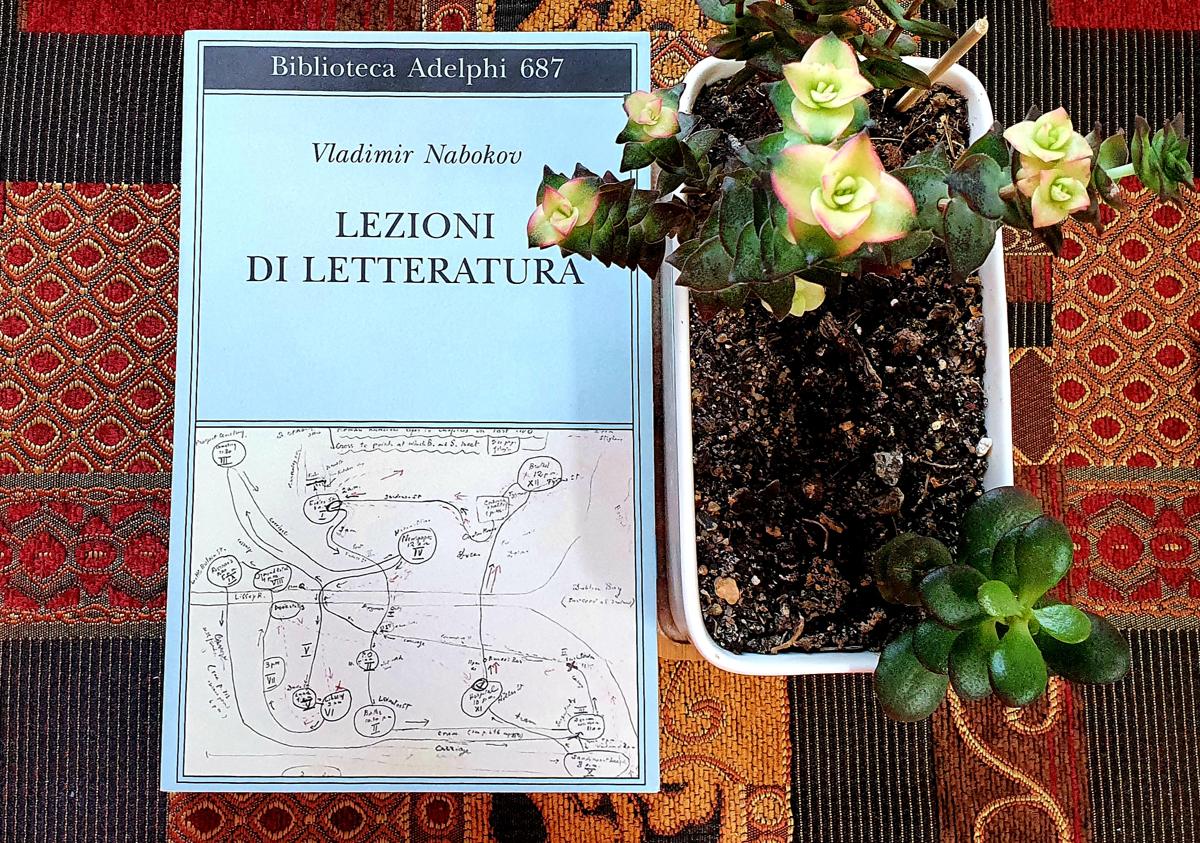

The volume, recently released in bookstores and printed by Adelphi with the title of Lessons of Russian literature, side by side and complete Literature lessons, already published in 2018 by the same publishing house with translations of the English version by Fredson Bowers.

If in some places the heterogeneity and sometimes the raw nature of the material to which Bowers must have had access is palpable, this is by no means a flaw; on the contrary, wherever one perceives the atmosphere of the university classroom, one imagines Nabokov’s gestures and mimicry as he immerses himself in the reading of some of his favorite pieces, or throws arrows against those translators guilty of having ruined a work of art . The multifaceted and complex personality of the author emerges clearly from the pages: the teacher, the critic, the artist, the exile, the man appear in turn; the reader can therefore immerse himself fully in his personal and all-encompassing vision of literature.

They must have been extraordinary years, both for the students (requests for attendance always exceeded the maximum limit of students who could be admitted), and for Nabokov himself: in that period he ended in fact Speak, I remember, he wrote Lolita and the stories of Pnin, conducted research for the translation of Eugenio Onegin and laid the foundation for Pale Fire.

Vladimir Nabokov is to be considered a sui generis teacher, almost radical because of the deep fracture he perceives between art and reality; it does not want to convey simple information, but to teach to read, to hear the text, to perceive the art and passion inherent in creation.

“It is certain that, however keenly, however admirably one examines and analyzes a story, a piece of music, a painting, there will always be brains that will remain empty and spines that will not be crossed by any thrill. […] It is necessary that you have within you a cell, a gene, a germ that vibrates in reaction to sensations that you cannot define nor can you ignore. Beauty plus compassion – this is the concept that comes closest to defining art ”.

His gaze captures, through reading, apparently insignificant objects and details, yet capable of illuminating hidden paths between words, on which the footprints left by the author are visible: he therefore makes the magic of creation shine. On the other hand, the obsessive domination of details is precisely one of Nabokov’s trademarks, appreciable only through the rereading, of which he was a staunch supporter. Reading, in fact, is never a mechanical action: “I tried to make you good readers who read books not with the childish purpose of identifying with some character, and not with the adolescent purpose of learning to live, and not with the academic purpose of indulging in generalizations. I have tried to teach you to read books for their form, their evocative power, their art. I tried to teach you to feel a thrill of artistic satisfaction, to share not the emotions of the characters, but those of the author: the joys and difficulties of creating “.