2024-04-12 06:26:49

In the fall of 1969, a young student at the German Academy of Fine Arts took a picture of himself loitering in front of European monuments. Sometimes in boots and riding breeches, other times debauched like a hippie, he raised his right hand in front of the Roman Coliseum, statues of French kings or at the foot of the Vesuvius crater.

The cycle was called Occupation. And its author, Anselm Kiefer, refused to explain it or accompany it with a condemnation of Nazism, which is why when the photos were printed by an art magazine, they caused an uproar. It is also revisited by director Wim Wenders’ new documentary called Anselm, which premiered at the European Film Days festival this week.

The poetic feature-length film shows how a provocateur became a respected author of monumental works that one does not normally see in a gallery. Today, 79-year-old Kiefer is one of the best-known living German artists, alongside Gerhard Richter and Georg Baselitz. He represented the country twice at the Venice Biennale, and had major retrospectives at the New York Museum of Modern Art, London’s Royal Academy and Paris’ Center Pompidou.

He never exhibited in the Czech Republic. The planned show in Prague’s National Gallery was canceled after director Jiří Fajto was dismissed in 2018. Wenders’ film now shows what the Czechs have lost.

“I didn’t want to provoke,” Kiefer claims in the archive footage, that while today German television regularly broadcasts documentaries about Nazism, the topic was not discussed in his youth. “There was silence around the Second World War, fascism and the Third Reich. We learned about it at school for three weeks. That’s why I wanted to hold up a mirror to people,” explains the artist, who was also taught by former Nazis at the art academies in Karlsruhe and Freiburg. The students did not know their past. And little was said about her at home either.

The first to break the silence was artist Gerhard Richter, who was 12 years older than him, and still managed to be a member of the Hitler Youth. Even as an adult, he painted the Nazis neutrally, the culprits as well as the victims. In the portrait dedicated to the Lidice memorial, Richter famously depicted his uncle Rudi, smilingly posing in a Wehrmacht uniform.

Photographs from the series Occupation by Anselm Kiefer from 1969. | Photo: Profimedia.cz

Anselm Kiefer was born during the Allied bombing in the spring of 1945, shortly before the past became taboo and the Germans started anew after the war. The young man coped with this at a time when the country was bringing to court bachelors and prominent figures of the Third Reich. When he posed in civilian clothes in the photographs, he may have been drawing attention to the presence of ex-Nazis at all levels of society.

He went to the extreme with his performance of hajj, which has been banned in Germany since 1945. He never wore the full uniform of his father, who, as a surgeon, enlisted immediately after his studies and operated on wounded soldiers at the front. At the same time, the young man refused to declare himself an anti-fascist, which is why, for example, the Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers called him an ordinary fascist.

“I was born in 1945. I can’t be sure how I would have behaved in 1939,” argues Kiefer in the film.

Blood and soil

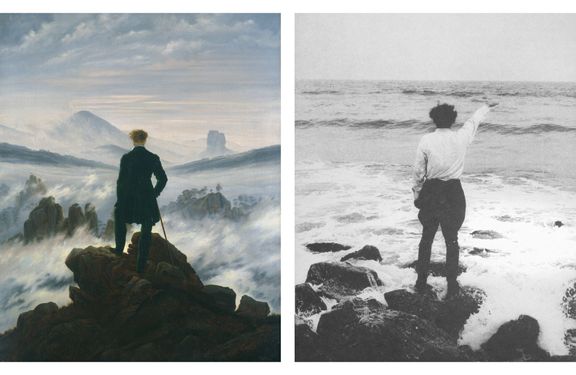

In one photo, he is hailing on the coast. It apparently refers to the painting Pilgrim above the Sea of Mist by the German painter Caspar David Friedrich from 1818, which seems to foreshadow his next direction. Despite the romantic tradition, Kiefer continued to the foundations of Germanic mythology, heroes of the Parsifal type.

“The core of his provocative strategy was a fierce determination to forcefully combine culturally acceptable elements of the German heroic and mythical tradition with unacceptable historical consequences,” summarizes art historian Simon Schama in the book Landscape and Memory, also published in Czech. According to him, even in the 1980s, Kiefer faced accusations that he “revels in a kind of demented Wagnerian cultism and promotes the very blood-and-soil mysticism he claims to reject.”

On the left is The Wanderer over the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich from 1818, on the right is a photograph from the series Occupation by Anselm Kiefer from 1969. | Photo: Hamburger Kunsthalle, Tate Gallery

The painter showed that Nazism was one of the consequences of Romanticism. But at the same time, he declares in the film that, as the year 1945, he felt an opportunity to wash away the Nazi ideology from tradition.

Meanwhile he was changing form. When he hailed in 1969, it was a mixture of performance art and conceptual art. As early as 1980, he exhibited woodcuts with mythical Germanic themes at the Venice Biennale. Only then did he focus on the creation of giant objects, and especially on painting. Today he is referred to as a neo-expressionist. Thematically, he moved through antiquity to Judaism and the oldest myths of mankind, in which he seeks answers to the most basic questions.

Not only romantics such as Caspar David Friedrich often painted ruins, in which Kiefer sees the rubble of bombed-out buildings from his childhood. Wim Wenders, also a German born in 1945, included footage of the post-war debris clearance in the film. Kiefer played in them as a child.

Ruins still appear in his works today, but in a shifted meaning. “You can’t just paint a landscape when tanks have passed through it,” he declares in the film.

He shows how today he creates monumental canvases measuring several meters in height. Kiefer works in a former warehouse on the outskirts of Paris. He applies paint to the canvas in giant layers. But then he also pours lead on it or places thistles, straw or withered sunflowers. He then burns them off with a tanning lamp in hand. All the while, the assistants immediately extinguish the fire behind him so that it does not get out of control.

At that moment, the nearly 80-year-old bald man, dressed from head to toe in black, looks a bit like a paraphrase of a Nazi with a flamethrower. The resulting painting is reminiscent of the scorched earth left behind by the troops. Pieces of charred books, parts of clothing or perhaps military equipment stick out from the multi-layered structure on the canvas.

Another painting depicts a winter forest drenched in blood. Snow dirty as from ashes, tree trunks scarred by the advance of the front. Land plowed by tanks. The view across the railway tracks evokes transports to concentration camps.

The documentary film Anselm by Wim Wenders was shown this week by the Days of European Film festival in cinemas in Prague or Ostrava. | Video: Janus Films

War poetry

Both parents of Kiefer’s favorite poet, the Jewish Paul Celan, died in the camps. He wrote “poetry after Auschwitz” in German, thus denying the philosopher Theodor Adorno’s statement that writing poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric, in other words that art cannot continue in its current form after such destruction.

Celan’s most famous poem Death Fugue is performed by Wim Wenders in the film. “Play that death / Death is the maestro from Němec / He’s calling, tune your violin deeper / After you rise up like smoke / Up in the clouds is your grave / There’s plenty of room for a person there,” reads Ludvík Kundera’s translation. The poem is told from the point of view of a concentration camp guard who writes his love while also sending dogs on Jewish prisoners.

For Anselm Kiefer, Celan remains an inspiration. He brought him to the topic of Nazism in his youth. As late as 2022, the artist exhibited a cycle of paintings dedicated to this poet in the Grand Palais in Paris.

In the same way, Kiefer has been accompanied throughout his life by the poetry of Ingeborg Bachmann, who came to terms with her father’s Nazi past and whose recitation is also heard in the documentary. Among other things, Bachmann wrote the poem Bohemia lies by the sea, referring to William Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale and expressing longing for a utopia that cannot be fulfilled. Kiefer painted the subject.

The painting entitled Bohemia lies by the sea from 1996 by Anselm Kiefer is in the collections of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. | Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art

In the film, Anselm Kiefer speaks mostly from archive footage projected on an old television. Wenders shows him riding his bike through the warehouse of his works, whistling between the monumental canvases, occasionally climbing up to one on an elevated platform or walking between them with a cigar.

A lot of it is probably impressive in 3D. Wenders, the author of classic feature films such as The Sky over Berlin or the documentary Buena Vista Social Club, shot a portrait of the dancer Pina Bausch in this way for the first time in 2011. He used the same technique now. But Monday’s screening in Prague’s Světozor cinema was two-dimensional.

Seven Heavenly Palaces stand on Anselm Kiefer’s property in Barjac. | Photo: Charles Duprat

Even so, the viewer will appreciate shots of monumental works on the big screen. Especially on Kiefer’s land near the French town of Barjac. About two hours away from Marseille, the artist built an area there, which he connected with a series of tunnels and filled with his creations.

There are submarines in glass cases, monumental planes cast from lead. Twenty-meter high concrete towers resembling shipping containers and referring to the cabal stick out from the landscape. It is not difficult to see in them another variation on the theme of post-war rubble.

Wim Wenders pays particular attention to the mysterious plaster torsos of female bodies. They are located all over Barjac and are named after various martyrs, from the Mesopotamian Lilith to the mothers of Roman emperors. All are missing heads, replaced by various symbols. Wenders keeps them whispering mysteriously, indistinctly in the film.

All the while, contemporary and archival footage from the artist’s life is complemented by live action clips, in which Kiefer’s son and Wenders’ great-nephew play the artist in various stages of his youth. They show, for example, how he writes to his later teacher, the famous artist Joseph Beuys, and takes to show him his paintings rolled up on the roof of the Volkswagen Beetle.

In 2022, Anselm Kiefer covered the Renaissance frescoes with an exhibition in the Doge’s Palace in Venice. | Photo: Georges Poncet

The fiction and documentary lines will intersect in 2022, when Anselm Kiefer exhibited in the Doge’s Palace in Venice. At that time, he overlaid the beauty of Renaissance frescoes by Jacopo Tintoretto or Paolo Veronese with monumental apocalyptic scenes.

Just as he once held up a mirror to the Nazi past, here he seemed to show the flip side of the gold-decorated halls, opulence and wealth of the former powerful republic that militarily dominated part of the world.

Kiefer called the project When These Writings Are Burned, Some Light Will Finally Shine. The paintings with parts of the scorched earth have an obvious meaning here, where the fire symbolizes not only destruction, but also purification, the first step to salvation, redemption and a new beginning, just as German post-war art was born from the ashes. Except that at the end of Kiefer’s life it is no longer about Germany in the year zero, but figuratively about all of humanity. Between the two canvases, a biblical ladder juts up to heaven.

Anselm Kiefer has come full circle. And the second one describes Wim Wenders, when at the end he lets the child actor meet the artist in his former childhood room. Apparently to show that Anselm Kiefer had enough for his whole life with the themes that brought him to art.

Film

Anselm

Directed by: Wim Wenders

The film was presented by the Days of European Film festival.