The public letter issued by singer Neil Young about two weeks ago with an ultimatum against streaming service giant Spotify, in which he demanded that they choose between him and Joe Rogen’s popular podcast – re-sparked the heated discussions against streaming services, and was enough to once again crown Spotify as a giant. The evil that exploits the artists from whom he makes a living. Young was joined in protest by other artists such as Johnny Mitchell, Graham Nash, David Crosby and Stephen Stills.

Jonathan Kutner, who has worked for the streaming giant for more than 3 years, thinks the outrage directed at Spotify is wrong: “The amounts that streaming broadcasts put in creators are obviously too low,” he writes, . In a special column published here he explains how royalties are calculated for artists and argues that “in order to correct streaming royalties one needs to correct the balance of power that governs the music industry.” And to do that you have to go back at least 17 years.

A. For 17 years I have been looking for: Where is the money?

“In 2005 I worked with the Izbo band. It was a strange time in the music industry, where piracy accustomed us to the idea that you could not make money selling albums. To the top ten in the annual parade.We learned this a year late, and when the royalties arrived the detail was only one line – “Radio Australia”. There was no way to know how many plays were, at how many stations, or whether the songs were also played in pubs or parties. Track the money.

13 years later I joined Spotify as a senior editor. The world has changed. I have seen Israeli artists – from Neta Barzilai through Noga Erez to iogi – enjoy unprecedented international success. Streaming allowed them to know in real time where they were gaining momentum and how much. But the old question remains – where is the money, and what does it do to the artist’s pocket?

Although I have worked at Spotify for 3.5 years, what is written here is not based on information I have accumulated in the company.

The issue of global royalties has occupied me obsessively since the story with Izbo and throughout my career in managing artists and labels. Much of the writing is based on the deliberations of a committee of the British House of Representatives that convened last year to study the streaming economy, and hosted a wide range of senior figures in the music world and some musicians I love like Johnny Greenwood and Guy Garvey. I have followed most of the discussions that are also available in the video, but would recommend to anyone interested to at least read the conclusions (the full in-depth report, or a summary in an interactive presentation).

B. So how do royalties actually work?

When a song is played in public – on the radio, television, bar mitzvah or even streaming – there are two main royalty channels that the player is required to pay: recording royalties (master), and writing royalties (songwriting) for the use of words and melody.

That is, the song I wrote could have different performances. For every performance of such a performance I am supposed to receive songwriting royalties, but the master’s rights to any recording belong only to the master’s owner, who are usually the record company or the artist himself.

Taylor Swift / Photo: Associated Press, RJoel C Ryan

Songwriting royalties are usually managed and collected by collection associations, such as ACUM in Israel, which are signed by many writers. This is money that the record company usually does not touch. It goes directly to the writers, except for a fee to the association.

Master royalties, on the other hand, are usually managed and collected by the record companies, or their associations (for example, the federation, or the Israel Defense Forces, in Israel). This money is divided between the record company and the artist, according to the deal between them.

In the “classic” tin of the three Universal giants, Warner and Sony, which control the recorded music and the “major” machines – the artist often receives only 20% or less, and this too sometimes only after the company returns the investment; A relic of the days when it really cost a lot to record and distribute music, and record companies would invest considerable sums in artists.

It is important to understand that the amount of royalties received from any broadcaster is not the result of legislation – but of market standards set in accordance with the negotiations between the rights holders and the broadcasters.

Over the past 20 years, the industry has undergone many dramatic changes: from the wave of piracy at the beginning of the millennium that destroyed much of the revenue to the wave of independent artists that led to a decline in recording expenses. All of these affect the dynamics and negotiations between the rights holders and the broadcasters and hence the level of royalties.

third. And how do streaming royalties work?

Streaming is a strange and new chicken, but even here you pay in the same two channels of royalties: master and songwriting. The distribution key, in all streaming services, works like this: Calculate all the revenue in the country from subscription fees and advertisements in a certain period. The service takes about 30% for itself and spends the rest in royalties. 50% -55% go to the master rights holders, the remaining 15% -20% to the songwriting rights holders.

According to the existing key, the master’s rights are about three times equal to the songwriting rights. Why is this the case? Streaming broke into the world in 2008, after seven years in which the war on piracy was a complete failure and global revenues from physical sales of records fell by at least half. The majors identified in streaming a possible lifeline. It can be assumed that the fact that together they hold the master’s rights of about 80% of the recorded music in the world, gave them greater bargaining power than any songwriting rights holder.

Johnny Mitchell / Photo: Reuters, Fred Prouser

This ratio is a big part of the reason many cases of veteran artists are rightly shocked by their streaming revenues: most royalties, even in the streaming era, remain with record companies. In independent artists, however, the situation is different – they own most of the master, so it can be said that this attitude works in their favor. This is why, for example, Taylor Swift has re-absorbed much of her old material – when she owns the master, the royalties she sees are much higher.

D. How much is a stream really worth?

Streams (or “streaming”, an unfortunate translation but that’s what it is), do not have a fixed rate. The value varies from month to month depending on the service income in the country. In the Nordic countries, where almost all music consumption has switched to paid streaming – the value is often higher than in a country like Israel where the majority of the population does not understand why you have to pay for music at all. This amount also varies because a subscriber pays a fixed amount regardless of the amount of songs he has heard.

The absolute numbers in many items on the subject create a false impression, but it is correct to use them to understand the ratio between the payments in the various services. It is also important to say that different sources give different estimates, so the numbers I will mention here are a kind of weighting: Apple Music pays between 0.006 and 0.007 cents per stream; Amazon and Dizer between 0.004 and 0.005; Spotify between 0.0036 and 0.0043; And YouTube pay in the region of 0.002 cents per stream.

From all this, it can be understood that the level of royalty is almost unrelated to how much of the revenue the streaming service keeps to itself. Spotify’s low royalty relative to Apple is directly related to the fact that it has a free track and Apple does not.

So back to the question how many streams are really worth? Take for example a song that made a million streams – which is not a very high number: according to Spotify, in 2020 alone there were more than 207,000 songs that garnered a million streams or more in the service. Dennis Lloyd’s huge international hit, for example, has already garnered 747 million streams on Spotify. A local Israeli hit, for example a successful song by Omar Adam – can reach the area of 10-15 million streams. “Imagine” by Shlomo Artzi, which came out 11 years before Spotify was launched in Israel – has accumulated about 6 million streams on Spotify.

Omar Adam / Photo: Shai Franco

One million streams is worth, in terms of royalty to the rights holders, about $ 4,000 on Spotify and about $ 7,000 on Apple Music. For the sake of abstraction (very crude), let’s say that the artist’s deals with the rights holders allow him to keep 20% of the royalties. From Spotify it will earn something like $ 800, and from Apple Music about $ 1,400. Not amounts that you can make a living from. And as mentioned, they are not a function of the decision to “pay more”, but of the revenue of the artist’s streaming service and deals with the rights holders.

God. What is the benefit of streaming to the market?

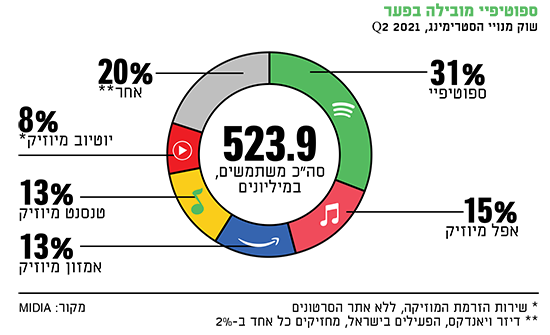

If you look at how much streaming services are bringing to the entire industry, another side also becomes clear. Spotify entered the music industry about $ 5 billion in royalties in 2020, and YouTube (much thanks to the paid service ‘YouTube Music’) is not far behind it in second place with $ 4 billion from mid-2020 to mid-2021.

To understand how significant this is one has to go back: in 2001 the industry as a whole made $ 23 billion. An amount that shrank to $ 14 billion in 2014, and since then the industry has grown to revenue of $ 21 billion in 2019, when almost all of the growth came from streaming. That is – on a global level streaming saves the music industry. The problem is that the money goes to the creators.

The model of all streaming services is similar, the fact that Apple Music pays a few thousand cents more does not mean that an artist can make a living from them more than Spotify (especially since Spotify has more subscribers, so artists’ revenues will usually still be greater at Spotify). Even if all streaming services were to pay the same royalty, its significance to the artists’ livelihoods would be minor.

In the current reality, the only way to have a significant impact on artists’ pockets is to raise subscription prices. Streaming services are indeed trying to raise subscription prices slowly – but it is not easy in such a competitive market and at a time when people are not happy to pay for music.

Last year an artists’ campaign demanded that Spotify increase royalties to one whole cent per stream. But according to a calculation by an industry magazine, this will require an increase in the subscription fee to about $ 100 per month. Even as a heavy music consumer who likes to spend money to support artists I can not imagine paying $ 100 for it. Most people will have a hard time justifying $ 30 as well.

But keep in mind that the artists will also receive this cent after all the realtors along the way have taken their share.

and. There is a choice, the method must be changed

In the long run, it is to be hoped that streaming services will indeed succeed in trying to raise prices, and that future legislation may force them to raise even more, and that most customers will not run away in the process. Until that happens – the most important thing is to take care of the way the money is distributed, and make it fairer for the artists.

The conclusions of that British committee relate precisely to the subject. Some of the directions it has examined are related to the change in the way royalties are calculated within streaming companies, and some to restrictions on record companies, both in terms of contracts with artists and in terms of the ability to put pressure on streaming services.

One of the possible models that has emerged is beyond the royalty calculation method called User-centric – the sheet is too short to explain the complexity of this method, but according to studies done it is not clear how much it will create a significant change in artists’ income.

Another direction that came up in the committee’s deliberations was a solution promoted by Tom Gray, a musician (from my favorite Gomez band) and a member of the music industry: an initiative to create a third royalty channel that is not a master or songwriter but a type of promotional royalty called ER – Equitable Remuneration. . These royalties are paid to promotions through a collection company, and the record companies do not touch it. Gray proposes to apply this royalty channel to streaming as well.

Such an amount is likely to be cut from the portion of master royalties, and record companies are likely to object. But the committee was convinced that this could be an effective way to compensate artists for the use of their songs on streaming, and included it in its recommendations. If this channel is enshrined in legislation in the UK, it could open the door to a significant change in the way artists are paid for streaming around the world.

If we want to bring about real change in the way artists are rewarded for their music, we can not just settle for demanding streaming services to increase royalties. We must make an effort to understand why the situation is as it is, and to demand that the legislators do the same. Legislators need to work, together with industry, on new models for calculating royalties and on new models for linking rights holders and artists – models that restore systems to fairness, using all modern technological tools.

Sold by Tower Records to Senior Spotify Editor: Jonathan Kutner’s Career

Jonathan Kutner is a music director, label manager and music editor with a career of 20 in the music industry. He lives in Berlin, where he moved in 2018 to work at Spotify as a senior music editor. He was responsible for the launches and musical content in Israel and Greece, and was also a member of the company’s global indie committee. Last year he finished his job there.

And yes, his father is Yoav Kutner. But despite this he started his career “from below” as a salesman at the record store Tower Records. Between Tower and Spotify, he worked in management positions at a number of Israeli labels, including Leibla (of the legendary promoter Asher Bitansky), Anova Music (an Israeli label focused mainly on overseas bands) and Horse (a Hebrew indie label he founded himself). Kutner worked. With dozens of artists, among the most prominent of them: Izbo, Aya Korem, Amit Erez and Secret C, Butcher, Ruth Dolores Weiss, Yuppies with Jeeps, La Band (by Guy Shemi), Neta Weiner, System Ali, Electra and many more.

The column published here is the incarnation of a post posted by Kutner on his Facebook page in which he explains, based on his experience and familiarity with the market, how the royalty system works – in and out of streaming – and how to correct the distortions created over the years.

Thin lead