2024-09-12 23:25:26

- There they “shut up” the most dangerous political prisoners, gave them 250 g of bread and a ladle of slop a day

- Inside, Geshev’s granddaughter talked about her grandfather with admiration and complained that the authorities left them only one house

- They are moving Tsvetana Germanova to “Belene”, she expects to be executed

IN previous issue of “24 hours – 168 stories” we told you part of the life of Tsvetana Germanova, known as the last woman who survived the communist death camps “Bosna” and “Belene”. She spent 40 months in exile on charges of anarchism. They punish her, shoot her several times, but she survives. Germanova died on February 19, shortly before her 96th birthday, and was the only one to describe what she experienced in her book “Memories from the Camps”.

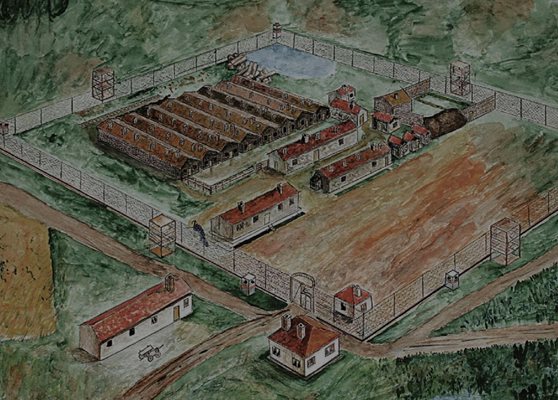

After the death of Georgi Dimitrov on July 2, 1949.

the “Bosna” camp was filled with political prisoners

Some were brought straight from the street. The rooms were full. There were over 300 women. Some of them slept on the floor. Among them were the operetta singers Milena Baramova and Tsvetana Mihailova. They had a performance and after the end they decided to treat each other for the good success. They ate, drank and sang, but by doing so provoked the arrival of the militiamen, who accused them of rejoicing over the death of Georgi Dimitrov. They were arrested and sent to the camp.

Of the women from the so-called highlife Germanova never forgot 3 more ladies – Mimi Kalcheva-Gesheva, granddaughter of the then famous policeman Geshev, Sonya Salabasheva and Nadezhda Stoyanova, who were connected to the royal family.

“Mimi was an avid rider,

knew gen. Krum Lekarski, who during the war was a deputy to Gen. Stoychev, respectively deputy commander of the First Army – Tsvetana Germanova tells in her book “Memories from the Camps”. – After the end of the war, they staged a trial against Lekarski and demanded that Mimi testify about his “enemy” activities. She refused and ended up with us. Personally, she accepted me more as an exotic, as an unknown and interesting specimen. He told me about his rich and famous family, about his grandfather Geshev. He said that everything was nationalized, they were left with only one wooden house on Gornobanski road, and he ordered me to meet again after our release. When I used to go to Sofia, I would look at the house and I could tell by the appearance that the owners were not in a very good economic condition and I didn’t want to cause them inconvenience. I did not look for her, but perhaps she had changed her residence. I’m sorry, she was a decent person.”

In the camp, the second woman –

Sonya Salabasheva, was called the tsar’s mistress

She was about 40 years old, a real beauty. She behaved extremely dignified, but she did not come into contact with the political prisoners, only the criminal ones. She was imprisoned because of the accusation that she illegally exported a child to Italy. She only admitted that there really was such a person who was a member of the royal family, but who the child belonged to, who ordered her to do it and to whom she handed it over, she did not say. Sometimes the women jokingly asked her

whether the child belongs to Prince Boris III

or to his brother Cyril. The general opinion was that it belonged to Prince Preslavski, because he was known for his bohemian lifestyle.

“She often asked me about the village of Studena, Pernishko, where her husband worked as an engineer during the construction of the Studena dam,” Germanova shared later. – She told me that her father was a pharmacist who owned the biggest pharmacy in Sofia, and other details of his personal life. I witnessed how the teacher Slavcheva called her a royal mistress, and Sonya replied: “A mistress, but a royal one, look at her, what you look like. No one will even look at you. You will remain an ugly and cruel woman.”

The third woman, whom Germanova never forgot, had nothing in common with Mimi Kalcheva and Sonia Salabasheva in terms of education, culture and behavior. Nadezhda Stoyanova worked in the palace as

secretary to Queen Joanna

and accompanied her everywhere. In the camp, she demonstrated strange behavior. She was unclean and always chewing grass or something. But when, already free, other campers visited her, they were surprised by her completely different appearance, so they thought that her behavior in “Bosna” was a simulation.

Until the end of her life, Tsvetana Germanova will remember something else experienced in this camp –

the creation of the “Black Company”

This happened in 1950 and was the new punishment of their “educators”. 12 older female political prisoners were dressed in rags and made to live in a chicken coop. The official version was that they were accused of sabotage and shoddy digging of corn. They were only entitled to 250 g of bread per day and one scoop of boiled mustard – buren, which they fed to the pigs. However, according to Tsvetana, the reason was completely different.

“The reason for the creation was not sabotage, but an attempt to cover up a crime of the manager of the Kasabov camp – says Germanova in her book. –

He had a relationship with a criminal girl

She worked alone at the aviary. The girl became pregnant and was quickly released, and Kasabov and his family mysteriously disappeared overnight. I have no memory of the girl. I remember he was from Sofia. In order to divert the attention of the female campers from the manager’s crimes, they created the “Black Company”, including the women who they feared would not remain silent and insist on an investigation of the case.

All those punished were our friends and we decided to help them. Dr. Gacheva, Maria Doganova, Katya Partova and I tackled it. Kateto provided all her newly received package: butter, honey and milk powder, Dr. Gacheva prepared the sandwiches, and Maria and I placed them in the toilets under the tiles. We used to do that in the morning between 4.30 and 5.”

Not long after, they were caught and also sent to the “Black Company”.

For 3 months there, Germanova lived in hunger,

filth, lice and disease, but the only privilege was that she had no norm for the day and received no additional punishments.

Not long after, in late December 1951, the female political campers in Bosnia, considered the most dangerous, were ordered to pack up. They loaded them onto two trucks and took them to Tutrakan. There they spent the night in the basements of the militia. They thought they would be interned in Russia. The next morning, however, they left for “Belene” station. From there they were put on a motor boat that took them to Sturchetto Island – the women’s camp.

“On the very shore was the piggery, and further in on an artificial embankment there was an unfinished building – says Germanova in her memories. – It consisted of 3 rooms. In the evening they would lock us up, bring in a cart and

part of the room was being converted into a toilet

The other 2 rooms were used as an office and a bedroom for the manageress and the policewoman. Food was brought to us from the neighboring island of Persin, where men were stationed. About 30 women were set aside to work in the piggery and the rest to uproot trees. The island was small in area, but overgrown with dense vegetation – grasses and bushes, and very tall poplars. The task for us who worked on the eradication was to make a way and make the island habitable.”

However, she was quickly transferred to work in the piggery. She took care of 1000 pigs, which were in 20 boxes of 50. That’s how she spent 4 months. She admits that her work was not difficult, but she was very responsible. However, her thoughts were gloomy – Germanova was considered one of the most dangerous inmates and expected the worst to happen to her.

“On the morning of April 30, 1952, a group of 10 women, including me and Maria, were singled out for inspection, and the others went to work,” Tsvetana recalled in an interview. – We immediately understood that it was a matter of release. We all expected this because the men who came from Persin Island told us that with them

every day they released and the camps were about to be closed

We quickly put on our civilian clothes and were taken to the coast, to the building of the Ministry of the Interior, by motor boat. There we were met by several militiamen who made us sign declarations that we would no longer engage in fascist activities. Me, Maria and Penka Neikova refused to sign. We stated that we have never engaged in fascist activity and will not sign. The militiamen were surprised, did not know what to do and called their superior.

He glared at us and said: “You are not for release and I can send you back.” “Okay,” we answered in unison. Angry, he threw blank declarations and whispered: “Write whatever you want and leave, but remember that without a signed declaration you will not receive a release note.”

Me and Maria crossed out fascist activity and wrote anarchist one, and Penka wrote opposition activity and that’s how we got the notes. We left without saying goodbye to our friends. Such was the practice. They didn’t allow us to say goodbye, so that we wouldn’t deliver orders or letters. From Liliana, who kept the “beavers” money, we received money only for a ticket to Sofia. We left the clothes, and I gave Elena the rug I used to cover myself with. We waved to them from afar and shouted: “We are waiting for you!”.

We were leaving the Bolshevik labor camp

I remember the cricket with the mists, the flocks of ravens and the ringing of the bells.”

Tsvetana Germanova did not know where to go, but together with Maria she went to the family of one of her husband’s brothers Lubo. They were very happy with them. For hours she waited for her husband to come home. He was more than surprised to see her at home. The two promised each other that they would never be separated again. They started to put their lives in order. Lived in different places in the country since

they always had problems because Germanova was being watched

Years later, she even found listening devices in her house.

However, until her last breath, Tsvetana Germanova remained true to her convictions and freedom.