Updated:

Save

joint history of Ellen Mosley y Lonnie Thompson begins in 1969, during his fourth year at Marshall University (USA). He worked for the Geology department and she for the Physics department. Perhaps that was why they had never crossed paths. Even a Christmas party. In that celebration the hours passed, and the drinks were encouraging the staff. “In the end, there were only two sober people: Lonnie and me,” says Mosley, who now uses the compound last name Mosley-Thompson because she soon after married the guy who offered to give her a ride home. From that night not only was a personal relationship born that lasts more than fifty years; There was also a pair of excellent glaciologists who have managed to rescue 7,000 meters of ice in 64 expeditions, a witness to the history of the planet’s evolution over the last 800,000 years and which holds the clues about the uncertain future that awaits us.

In the early 1970s, Lonnie is offered a position at Ohio University and the opportunity to travel to Antarctica. His adventurous spirit makes him accept. Meanwhile, Ellen finishes her Ph.D. When her husband and her companions return from each expedition, she shows him images that make him start to ‘bite the bug’ of the adventure. So much so that she chooses the subject of her doctoral thesis to analyze the indissoluble dust of some ice samples to learn about the climate of 900 years ago. Because the ice, beyond water, contains from ash to pollen from other millennia, including ancient viruses and bacteria trapped as in a time capsule that shows a kind of photograph of the Earth in other ages. And not only the past counts, but also the future: carbon dioxide and methane are locked up here -the Arctic contains one of the great reserves of natural gas-, to later be expelled over time with the melting of ice. A natural process that, however, has been accelerated in recent decades, further worsening the problem of climate change.

“Glaciers are like an early warning system. And the people who live nearby can see very clearly the warning that the planet is giving us”, explains Lonnie Thompson, who talks with ABC at the headquarters of the BBVA Foundation in Bilbao. In a few hours, he and his wife will collect the Frontiers of Knowledge Award in the Climate Change category, awarded “for advancing knowledge and understanding of climate change in the past and present through their persistent dedication to eyewitness research of ice in high mountain glaciers, which are rapidly disappearing in the tropics and mid-latitudes,” according to the jury’s minutes.

From Greenland to the Andes

They are first-hand witnesses: their expeditions over the last forty years have revealed a dramatic retreat of up to 93% in glaciers in New Guinea over a period of 39 years (1980-2018); 71% on Kilimanjaro (1987-2018); and 46% in the Peruvian glacier of Quelccaya (1976-2020). “In the 1960s there was hardly any talk of climate change. Today, however, everyone knows that it is a reality, although many choose to ignore it. Because standing up to the problem is much more complicated than acting as if nothing were happening, “he says. Ellen Mosley-Thompson.

After these early forays into Antarctica, Thompson specialized in high mountains. The Himalayas, the Andes or Kilimanjaro have been some of their destinations among the 64 expeditions to their credit, including one in 2019 to Huascarán, one of the highest peaks in the Peruvian Andes and from where they extracted an ice core of 471 meters. This nucleus also ended up in the enormous collection that is kept by the University of Ohio.

He has anecdotes to write several books. On a trip to Papua New Guinea he and his team were surprised by some unfriendly Indians who they had to meet. Some of them carried machine guns. They explained that they worked all over the world, extracting ice. The locals told them in turn that their gods lived in the valley and that their heads were located on the glacier that the team intended to climb. “It was like extracting the memory of his divinities directly from his head,” he says. The town council met and debated for a long time. The older ones believed that those masses of ice had always been there, but the younger ones insisted that the glaciers, and with them their gods, were retreating, and they had to accept the help of those westerners armed with crampons who climbed the ice. “In the end they let us go. Many times success depends on luck, and that day we had it.

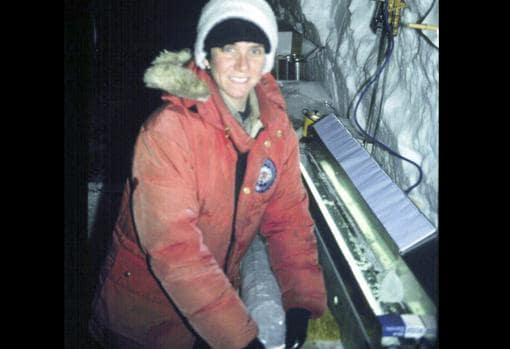

Mosley-Thompson first visited Antarctica in 1982, although in 1986 she became the first woman to lead a mixed expedition (she was the only woman) to Antarctica. “Another researcher had done it before, but she had a team made up only of women,” says the glaciologist, displaying her palpable humility. That trip was not without setbacks and the plane that she had to go to pick them up could not find her camp. In the middle of that place “with an incredibly clean and pure air, and a great silence thanks to which you can listen to your own thoughts”, describes Mosley-Thompson, she decided not to sit and wait and continued drilling through the ice. This is how they obtained two 200-meter-long ice cores that told the story of 4,000 years ago. Thanks to those samples, science found for the first time the traces in the ice of Antarctica of a huge unknown volcanic eruption in 1809, which contributed to causing the ‘year without a summer’ of 1816, in which it snowed heavily in places near the equator , such as southern Mexico and Guatemala.

New goals

Since then, he has led nine expeditions to Antarctica and six to Greenland. “I used to love the cold, but now I don’t like it so much,” he laughs. His face becomes serious to delve into the day to day at base camp, in which the group is isolated, only connected to the rest of the world by radio. “It is a very challenging environment and the group, which normally consists of five or six people, has to be self-sufficient: in addition to drilling through the ice and taking cores, you have to live together. That’s why I pay a lot of attention that the members of my team do not have too much ego. That doesn’t come in handy on expeditions.” For his part, Thompson, who, like his wife, has turned 74, has already set his next goal: the Quelccaya glacier in Peru. Making this trip will be a kind of ‘closing the circle’, since from here he extracted the first ice core outside the poles in the 1980s, only after several failed attempts and many took him almost for a madman. “Being up there is something special: it makes you feel very small in all that big space. On a cloudless night you can see the entire Milky Way and you can understand for a moment what the planet was like before, when there weren’t so many people and so many lights everywhere.”

Both say they are optimistic about the challenge of climate change, although “almost out of obligation, because otherwise we could not do anything about it.” Even so, Thompson gives him a harsh description: “It’s like being in front of a terminal patient, who you know will get worse, but in no case will he heal. It’s really sad.” Mosley-Thompson has a similar view: “With the thaw, all of history is melting away. Although recovering these witnesses makes us provide evidence of what is really happening. We must hurry up and act.”

See them

comments