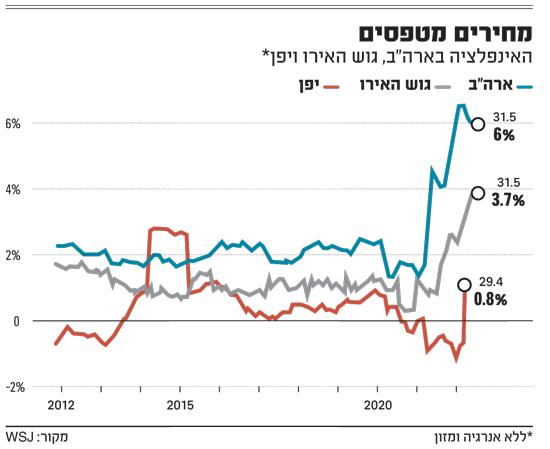

Think the role of the Federal Reserve is difficult? At least in the US the central bank can concentrate on the war on inflation. In Japan and Europe, central banks are also fighting against the markets and not just against price increases. This produces extremely strange and even contradictory types of policies.

The difficulties currently being experienced by the three largest central banks in the world mean that investors must be prepared for the possibility – not very reasonable but dangerous – that there will be large changes in prices. When central banks switch to full reverse gear without warning, care must be taken. Let’s see what the risks are.

The Fed has failed to curb inflation because it has spent too much time looking to the past, as part of its policy of being “driven by the data.” In doing so he left interest rates too low for too long. By sticking to this mantra that ‘data is everything’, the bank risks backing up the error in the opposite direction, raising the chances that the bank will be responsible for the next recession and then be forced to make a 180-degree turn. Since the markets have only just begun to price the recession and the subsequent decline in profits, such a move is likely to be painful.

The interest rate will rise until “something breaks”

Last Wednesday, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell went even further, saying he would not “declare victory” over inflation until inflation has been declining for several months. This will make it harder for the Fed to stop ‘belt tightening’.

Powell talked about learning during an empirical experiment in which it will be examined what level of interest rates will succeed in slowing down the economy enough. My analysis of the situation is that the Fed has pledged to keep raising interest rates until something breaks.

The European Central Bank (ECB) has a similar problem: politics. Last Wednesday, the bank held an emergency meeting to address the problem of Italy and, to a lesser extent, Greece. The European Central Bank wants to cool Italy’s bond warming, where the ten-year yield rose to 2.48% above the German bond yield, before falling following ECB intervention.

Unlike a decade ago, when the then Governor of the European Central Bank and now serving as Prime Minister of Italy, Mario Draghi, promised to do “everything right”, the action of the European Bank this time happened before the fire broke out, which is commendable. But the interim step of reorienting bonds close to maturity, acquired at the time of the plague as aid to eurozone countries in difficulty, is still a relatively small step.

The European Bank has promised to speed up work on building a long-term solution to deal with the fragmentation, but this is where it has encountered politics. The rich north always agreed to send money to the hard-working countries (in the south) but it had certain conditions. This is to make sure that they will not use the low bond yields as an excuse to take out additional loans, which later on they will not be able to meet their repayments.

But until the flames engulf the economy, the struggling countries are not interested in the embarrassment – or the political catastrophe – of agreeing to be overseen by the International Monetary Fund or other European countries.

Politically toxic scenarios

It will be difficult for the European Central Bank to buy Italian bonds to keep yields low while raising interest rates elsewhere. At the very least, it will have to enforce stricter policies vis-à-vis other countries than it should have done otherwise. At worst it is a recognition of risk. That Italy could reach insolvency as happened to Greece, and that would crush the capital of the European Central Bank itself.The two scenarios are politically toxic.

At present, Europe’s inflation problem is different from that of the United States, because wages in Europe are not rampant. Which currently stands at 150% of GDP, and it does not matter how much the European Central Bank will reduce the spread between Italian bonds compared to German bonds.

Even a low risk of Italy plunging into trouble justifies a neglect of its bonds, with the higher yields materializing themselves. When higher yields increase the risk of insolvency, they make the bonds less attractive – not more attractive. If the market were allowed to operate uninterrupted, it would push their return upward in an endless spiral.

The Japanese bank has better chances

The Bank of Japan is also fighting the markets, although compared to the European Central Bank it has a better chance of winning. Investors bet that the Bank of Japan would have to raise the ceiling on bond yields, called controlling the yield curve. In principle, the Bank of Japan could buy an unlimited amount of bonds, so that if it wanted to it could leave the ceiling in place. But if investors thought inflation justified higher returns, the Bank of Japan would have to buy ever-rising bonds because investors would not want them, as the late economist Milton Friedman noted in 1968.

Japan is the country that has the most successful case among the developed countries for justifying a light monetary policy. While inflation is above 2% for the first time since 2015, almost all of it can be attributed to global food and energy prices, and the pressure to raise wages is not great. Excluding fresh food and energy, annual inflation stood at 0.8% in April. Not exactly a cause for panic.

Still, inflation has risen and the risk is mounting that the Bank of Japan will have to give up, leading to a change in bond yields – exactly the kind of change that could resonate in markets around the world. They were hit hard, and some were forced to close.Japan is much more important than Switzerland, which in the past week has once again shaken the currency markets after an unexpectedly soaring interest rate rise caused a big rise in the Swiss franc exchange rate.

All of this could have been avoided – central banks are quite smart. But large-scale mistakes are more likely to happen than in the past, which means the risk of extreme market events is rising. For investors, this means acting with caution.