Am; lk

This month, NASA unveiled rare footage from the James Webb Space Telescope. He is the most effective director in NASA’s history.

The article was published in the Success Science section of the Wall Street Journal, a new column that seeks to answer the question – why do people, companies and ideas succeed or fail?

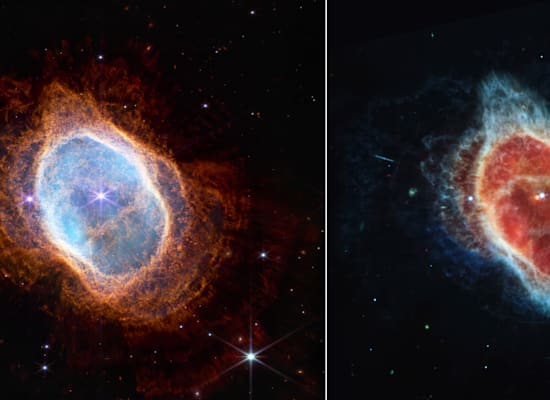

The James Webb Space Telescope, first unveiled this month by NASA, is a powerful observatory; so powerful that the Hubble Space Telescope’s mourning telescope (which has orbited the Earth since 1990) looks like binoculars. Webb is currently more than a million away. And half a mile from Earth in an extraordinary adventure in outer space, which some believe can change the way we perceive life here.

But for all that to happen, the James Webb Space Telescope just had to work. “The distance between success and failure is enormous,” says Thomas Zorbocken, head of NASA’s director of science missions. “But individual actions are needed to move between them.”

The release of the first images of the telescope is a groundbreaking moment for a project they have been working on for decades, and those who are most excited to see them are the people responsible for it, who thought they would never reach a moment. Webb has hovered for years much closer to the wrong end of the spectrum between failure and success. It cost so much money, and was delayed so long that the mission was almost canceled several times. But despite the scientific and engineering investment devoted to the telescope, what made the change was something completely different. In fact, it was someone.

When we think of NASA’s great successes we think of Neil Armstrong. That’s exactly how we should catch Greg Robinson.

He is the man who turned the resounding failure into an unreasonable success, a process that began in 2018, when NASA promoted him to the position of director of the Space Telescope program. The task he was given was to send a telescope into orbit around the sun.

Greg Robinson / Photo: Reuters, Robin Platzer / Twin Images

Out of a team of 10,000 people who worked on a $ 10 billion project, one person made the change. It may have been contrary to expectations, and it’s not something you would find out in a conversation with him, but no one in the world has a bigger role in launching a web to his track last year’s Christmas than Robinson. “The most efficient mission manager I’ve ever met in NASA history,” said his boss.

Such a level of praise would have sounded excessive had it not been for Webb’s mission – to explore the history of the universe from our solar system to distant galaxies – would not have been so extraordinary. This is because Webb is not a telescope, but a time machine: looking billions of years into the past, with infrared vision, which is 100 times sharper than that of the Hubble Telescope, it allows us to trace two fascinating lines of inquiry – where did we come from and are we alone?

John Mater, the Nobel Prize-winning senior scientist who has worked on the Web, has been preparing for decades to answer these questions. When an Italian colleague asked him where he got his inspiration from, he thought of Michelangelo’s work “Human Creation” on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican. “We don’t really think it worked that way,” Mater said of Michelangelo’s fresco, “but how did it work? For me, that’s the question.”

Captured command of a broken crew

The Telescope Web spent most of its days as an unemployed interstellar satellite, until it was launched 15 years late and in excess of $ 9 billion from its budget. An article in the British Nature magazine, which he largely praised, also included a warning: “No one should ever build a telescope the way NASA built the Web.”

But there was another problem. There was a strained relationship between NASA and its chief contractor, and scientists, engineers and technicians had communication difficulties. NASA needed someone to make the task too ambitious – and Robinson took command of a broken crew in what later turned out to be a critical moment.

The problem was that Robinson already had another role: he oversaw the quality and performance of NASA programs. Perhaps modesty is one of the reasons Dr. Zorbocken particularly wanted him, but it was also probably one of the reasons it was not easy to convince him to accept the role. In fact, for the first time he refused. “Politely,” Robinson says. “And the second time he asked me I again politely refused.”

Finally, after Zorbocken begged, Robinson left the job he loved for a job at great risk that could turn into a big embarrassment at any moment, and the efficiency of meeting her deadlines was about 50 percent. “It’s another way of saying that with every day that the mission continues the launch is postponed by a day,” Zorbocken said. By the time the space telescope was launched, the time efficiency had reached 95%. “It’s almost a miracle,” he added.

Photos from the Web Telescope / Photo: Associated Press

To understand how optimizing a project can be considered a miracle one has to look at its complexity. This is a project that has almost no margin of error, but places of error where there have been everywhere. “A landing mission on Mars could have 70 failure points,” said Steve Jerzyk, a former NASA executive. Web’s system has more than 300 separate failure points, and each of these crashes could have sabotaged the entire mission.

This idea, that there are hundreds of different ways the mission can fail, is not even the scariest thing about launching a web. “A lot of our missions involve one new technology or two or three,” Robinson says. “In the web we are launching ten new technologies – an unprecedented thing, and as I have said many times, quite crazy.”

“Pretty crazy” is not exactly the scientific term worthy of Webb’s unprecedented engineering achievements, but it is fitting, because Robinson’s role is not limited to the scientific side. As an engineer with technical expertise and a bureaucrat with excellent interpersonal skills, he speaks two languages: both that of NASA employees and that of politicians. His official responsibilities included “increasing integration and testing efficiency,” which sounds like laundering words outside the boundaries of a government agency.

But the obsession to succeed in the small things is what ultimately makes the big things happen. Space has always been a stronghold of people committed to exponential growth – but gradual: one small step and then a huge leap. The heroes of the universe are both brave but also boring. When I asked Robinson how he celebrated Webb’s success I remembered Armstrong’s words. Robinson replied, “A big sigh followed by a big smile.”

“Something no one expected”

Robinson (62)’s work at NASA makes him a kind of astronaut himself. He grew up in Virginia, the son of tobacco growers educated in racially segregated schools. He wanted to be so many things when he was little, but “building satellites was not one of them.” He studied at the University of Virginia Union on a football player scholarship, and was transferred to Harvard University, where he studied for his undergraduate degrees in mathematics and electrical engineering. It was not long before he began working for NASA.

Robinson spent most of his career in various positions at NASA and from position to position his responsibilities grew. There he developed his quiet and sincere leadership style, which led him to lead the telescope mission. When he accepted the position he had two goals. The first was to reduce human error: Make mistakes, but if you work on the same thing for 20 years you will make some mistakes. “The second thing was to bring in the perspective of outsiders,” who can notice things we do not see because we are so close to it. “

Webb’s team needed as many pairs of eyes as possible on the telescope’s sun visor – a tennis court-sized structure that folds into a missile, deployed in space and protects the telescope from extreme temperatures, which can reach 500 degrees. In Robinson’s first month in the role of the brackets that fasten the shield opened. A classic example of human error.

But this turned out to be an early test for Robinson’s approach, which immediately ordered a comprehensive examination of the system from every possible angle. The designers, contractors and engineers independently reviewed the plans against the hardware and compared their comments. “We discovered a few things that needed slight changes,” Robinson said to say the least. Robinson may call them “slight changes,” but they were the ones that led to the lunar photos the world foresaw this month.

Today the easiest way to make NASA employees giggle like children is to ask them what they want to get from Web: they want to discover new planets, they want to know more about the period after the Big Bang, they want to peek into the first galaxies, look into black holes and observe To dust clouds to understand how stars are born.

Even rocket scientists do not know what they will see when they point the telescope in the right places, and they have some speculation about Webb’s groundbreaking discoveries – but they mostly hope to find out they were wrong. In fact, this is one of the goals of the mission: to discover on Earth something different from what we have imagined to date. “Success means surprise,” Mater said. “There’s something out there that no one has yet expected.”