It’s been 45 years since NASA’s Voyager spacecraft blasted off from Earth, but the twin explorers still call home from billions of miles away.

We do ‘Hello, are you okay?’ “Call once a week,” said Susan Dodd, project manager for the long-term mission at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Laknada Flintridge.

Check-ins give Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 a chance to share their exact locations on the other side of the heliosphere, a remote region of the solar system whose magnetic field protects Earth and other planets from galactic cosmic rays.

During one of these calls in May, Voyager 1 sent out a bewildering signal.

Dodd said the data from the computer controlling its orientation “came back in mixed bits, mixed zeros and zeros.” It kept looking like gibberish.

“It’s like the check engine light is on,” added Bruce Wagner, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory engineer who oversees operations for the Voyager missions. We could not isolate it in a specific area.”

This computer is critical because it keeps the Voyager 1 communications antenna firmly pointed toward the Earth. Any failure or power loss would cut the longest phone call distance to mankind forever.

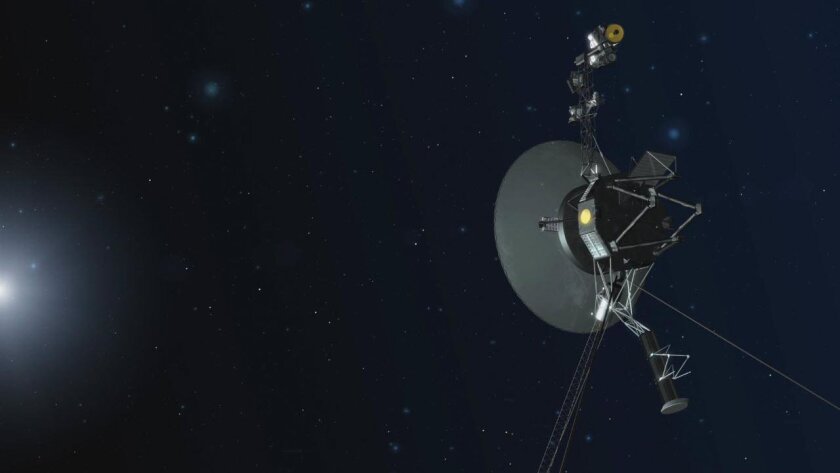

This artist’s illustration depicts Voyager 1 entering interstellar space, which is dominated by plasma shed by giant stars millions of years ago.

(NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Voyager 1 is more than 14 billion miles from Earth. It was launched from the Kennedy Space Center in 1977, reached Jupiter in 1979 and reached Saturn in 1980. Then it continued.

By 1998, it had become the most distant human-made object, flying farther from the Sun than the Pioneer 10 space probe. It left the heliosphere and entered interstellar space in 2012 (although scientists couldn’t confirm this until 2013). Voyager 2 followed in 2018.

Bill Nye, CEO of the Planetary Society, described the two spacecraft as “a vanguard of human thought and treasure”, classifying them along with decoding the human genome and formulating the theory of general relativity as among the first scientific achievements.

“What sets the Voyager missions apart is how much they have inspired people for half a century,” he said.

Voyager 1 is now so far away that it takes roughly 22 hours for transmission from the craft to reach us — traveling at the speed of light.

They are worth the wait. The dispatches contain valuable scientific data about interstellar magnetic fields, cosmic rays, and plasma waves.

Broadcasts from Voyagers are received by the Deep Space Network, which is three massive radio antennas in California’s Mojave Desert, Australia and Spain. They are scattered all over the world to make sure that at least one of them can target any point in the sky.

All three locations have a 230-foot antenna specifically designed to listen to Voyager. The further away they were, the more difficult it was to hear them.

Voyagers radios transmit signals at only 23 watts. By the time these signals reach the ground, they are reduced to the faintest of whispers, only a billionth of a watt.

The spacecraft is getting weaker, too. Each year their batteries lose up to 4 watts of power due to the decay of plutonium-238, the radioactive isotope that fuels them. (Solar is not an option because the sun is too far away.)

Survival is a series of trade-offs. With a limited source of energy, what can be sacrificed? What can be preserved?

The 230-foot antenna at NASA’s Goldstone Deep Space Communications complex near Barstow.

(NASA/JPL-Caltech)

From their remote locations, the two travelers make up the perfect laboratory – indeed Just Laboratory – to study the interface between the star and its surroundings.

“It’s really interesting to be able to get out into that medium and take measurements and understand what’s going on there,” said Bill Kurth, a heliophysicist at the University of Iowa who studies interstellar plasma waves. “It helps us understand what the environment around other stars might be like.”

But it is not easy. The signals are so faint that the 230-foot antennas of the Deep Space Network are too small to hear. To capture his plasma wave data, Kurth uses them along with three 112-foot antennas, “and that’s hardly enough,” he said.

Adding to the challenge is that the network is also making communications with dozens of other spacecraft, such as the Mars rovers and now the James Webb Space Telescope. He only communicates with Voyagers for a few hours straight.

This is not optimal because Voyagers have limited capacity to store the measurements they take, forcing them to transfer their data in a continuous stream. Missing information can be filled in by context, such as the way a baseball fan who missed a few hitters can tell what happened based on who’s on the field, the score, the number of hitters and the fans’ reaction.

All conversations with Voyager are faint, choppy, and slow. Wagner said that if there was an emergency, “we would have to send an order, wait two days or more, and then see what happened.”

So when abnormalities like the one that started in May appear, scientists need to be very careful.

The first irregular signals indicated that something was wrong with the attitude control computer guiding Voyager 1 into space. But the team knew the computer was already doing its job — if the antenna had been pointed in the wrong direction, the deep space network would have experienced a degradation in signal strength.

That’s why Dodd wasn’t too bothered by this problem. However, grading it was still a top priority.

It may be that high-energy galactic cosmic rays that Voyager 1 were no longer shielded from ejecting atoms from semiconductor wafers and affected the electronics, Dodd said. Or perhaps a decades-old computing system is malfunctioning due to deterioration over time.

After several months of investigation, this week the Jet Propulsion Laboratory team identified the culprit: Voyager 1’s attitude control system began sending its transmission data through a malfunctioning computer that distorted the data. The problem was resolved by instructing the spacecraft to return to using the correct computer.

Why Voyager 1 made the switch in the first place remains a mystery, and it’s worth solving because it indicates that something else isn’t quite right on the spacecraft.

Illustration depicting one of NASA’s twin Voyager spacecraft in interstellar space.

(NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Even if this problem turns out to be irrational, Dodd and her colleagues at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory are aware of the inevitable end-of-mission problem — the loss of power. It forces them to play a remote survival game.

“There is a constant tension between the instrumentation’s energy and the thermal management systems on Voyager,” Dodd said.

Voyager 1 heaters use a lot of energy, so in 2012 scientists began turning some of them off to conserve energy for communications and other critical systems. Fortunately, the devices kept returning data even though they were operating in cooler conditions than they were designed for.

Susan Dodd, left, Linda Spilker and Bruce Wagner are the Voyager command team at JPL.

(Myung Jae-chun/Los Angeles Times)

Over time, mission scientists had to get more creative. They shut down the thrusters that make very precise adjustments to control the antenna’s direction in 2019 and used the more energy-efficient spacecraft thrusters to move the entire probe instead.

“We have tougher decisions ahead,” Dodd said. Individual scientific instruments may need to be turned on and off, and only a few turned on at a time.

Voyager 2, which is 12 billion miles away, has the same battery issues. In 2020, a fail-safe mechanism unleashed by two power-hungry systems operating unexpectedly at the same time shuts down all of its science instruments for several days. (They are working fine now.)

Dodd hopes the spacecraft will continue talking to us for another five years. “I want to have this big party at 50,” she said, a remembrance that will begin the mission in 2027.

It’s going to be a tough day when the line to the last Voyagers ends.

“We’ll try everything we can to find out what’s wrong,” said Jet Propulsion Laboratory planetary scientist Linda Spilker, deputy project scientist for the Voyager mission. “But at some point, we just have to realize, well, maybe something happened this time.”