Tiger Global, one of the leading investment funds of the Corona era, updated at the beginning of the month about the intention of the leading partner, John Curtius, to leave his position next year. Curtius is not a well-known name among high-tech workers in Israel, but his departure has a great impact on the industry. He was the liaison between the big money of Tiger Global, a fund of 95 billion dollars, and dozens of Israeli entrepreneurs who were looking for quick financing, an extensive network of contacts and minimal interference in the board of directors. Money and industrial peace are not commodities that you get from most funds, and Israeli entrepreneurs have learned to appreciate this in the last two years thanks to funds like Tiger Global.

● One of the signs of the crisis: high-tech is no longer in the top 3 of job ads

● Israeli StixPay rose 255% on its first trading day: “A modest company that needs to score and break through”

In just two years, the fund carried out close to fifty transactions in Israel – without having a local partner and almost without visiting here. More than a third of the Israeli portfolio is made up of unicorns or companies that went public such as Iron Source, Sentinel One, Pagaia, Rapid, Scenic, Gong and Melio. Starting in 2020, Curtius became known in the industry as someone who would contact promising Israeli entrepreneurs, schedule a meeting with them in London, and often end it with a commitment to invest. The check would land in the bank account not long after.

The reactions in the local industry to the news of his departure were not long in coming. Curtius is a controversial figure among Israeli investors. They remember that time in the summer of 2021, when he arrived in Israel with his team with the stated goal of coming out with ten investment agreements within a week – a fast pace that Israeli funds are not used to and which, according to some investors we spoke with, indicates a superficial acquaintance with the companies.

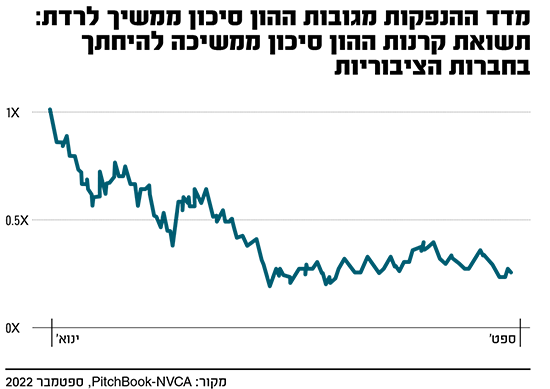

Other investors came to Curtius’s defense: his quick handling led him to win more deals, but did this help the fund’s bottom line? The results of Tiger Global’s private equity fund remain confidential but its hedge fund, which invests in public companies, lost 50% of its investments in the first half of the year. The private high-tech market is indeed reacting late to the crisis, but even there the value is starting to decrease and threaten the ability of the giant funds to generate value from their investments. The Sheblat firm reported that there was an increase in fundraising rounds, which represent a drop in value for growth companies and start-ups from 4% to 9% within a year of the total fundraising rounds.

At the same time, funds similar to Tiger Global, such as Coatue and Softbank, reported losses, including in private investments, suffered departures and layoffs – and moved to invest in young companies. Investments that require few resources embody greater profit potential, but also a significant risk component.

According to the research company IVC, Tiger Global almost completely stopped investing in mature Israeli hi-tech companies – those growth companies that used to raise hundreds of millions of dollars at a valuation of billions – and moved to tiny investments of a few million dollars in young companies. Curtius, meanwhile, continues to operate the fund until 2023, during which time he will leave Tiger Global with the goal of starting his own fund.

The investment managers at Sneek and FireBlocks have left

At the same time, the giant fund Coatue, which manages $70 billion and has made ten huge investments in Israeli and semi-Israeli unicorns – such as Fireblocks, Rapid, Kato, Deal and Tripactions, suffered a blow this month with the departure of at least three senior executives. Among the departures: Sebastian Düsterhoft, who managed the fund’s investments in the Israeli Sneek; And Luca Schmidt, who managed the investments in Fireblocks – the crypto transaction security company from Tel Aviv, and in Starkware – the encryption technology company from Netanya that uses blockchain networks. These came after the departure of senior partner Matt Mazzo, one of the foundation’s veterans.

The fund significantly slowed down its investments in Israel. In fact, after eight investments in 2021, this year it invested in a total of one Israeli company: Starkware. At the same time, it invested in the pre-IPO round of Tripactions, which is not Israeli – but has Israeli founders who live in the US and operates a small development center in Tel Aviv.

Until last September, the fund accumulated losses of 18.7%, and as of May – Koto reduced its exposure to investments by 14%.

Yossi Cohen, former head of the Mossad / Photo: Kobi Gideon – Chief of Staff

A similar trend was also recorded in Softbank, also a growth fund that invests in private and public companies. Yanni Pipilis, who managed the investment team of Softbank’s Vision 2 fund in London and was a partner in the recruitment of former Mossad head Yossi Cohen to the fund, announced his departure with other partners. He will join the CEO of the Vision Fund who also recently retired, Rajiv Misra, who was previously mentioned as a possible replacement for the founder of Softbank – Masiyoshi Sun.

The two will establish a new fund in the amount of 6 billion dollars with the addition of investors from the United Arab Emirates such as the Mubadala Fund and funds from the emirate of Abu Dhabi, which invest in the Vision 1 Fund. Absurdly, the fund was careful to emphasize with the addition of Cohen that the Vision 2 Fund has no investors from Arab countries. However, according to the assessment, the original goal in recruiting Cohen was to attract investors from the United Arab Emirates and Western Saudi Arabia.

According to research by PitchBook, Rajiv and Piphilis are not alone. Since 2020, half of the board members have left SoftBank’s Vision Fund, and the fund’s board has lost 11 out of 15 members. Last month, the Japanese fund embarked on a period of cutbacks during which 150 people, about 30% of the employees, will be laid off, following the losses. In the last two quarters, the Vision 1 and 2 funds registered a cumulative loss of 41.3 billion dollars.

The key figure in Softbank’s Israeli operation

Yanni Pipilis was a key figure in Softbank’s Israeli operation: from London he managed the identification of investments in Israeli companies, and the due diligence before any such investment. Cohen, who has previously spoken about his desire to run for prime minister and is now ending his cooling-off period, continues his position at the Softbank Foundation unchanged, and reports directly to Softbank’s founder, Masiyoshi Sun. Furthermore, Globes learned that he signed with the fund for another year.

Despite this, under Cohen’s tenure, Softbank almost never made large investments in Israel – with the exception of leading the investment in the cyber company Claroti and its merger with Medigate. Working under Cohen in Israel is Amit Lubovsky, an investment manager at Softbank who lives in the US and comes to Israel every few weeks in order to examine new companies for investment. “Amit and Yossi were very dependent on Yani and Brejiv, and when they left there was a bit of a halt,” says an executive familiar with Softbank’s operations In Israel. “There is a lot of rethinking there – this is a fund that recorded many losses – but the departures and layoffs in the fund do not add to the atmosphere.”

Softbank is also active in Israel through Ben Weiss, a Jewish partner born in Australia, who invests in young companies as part of Softbank Venture Asia – a fund located in South Korea that specializes in young start-up companies.

The funds that “rediscovered” the technology industry

Tiger Global, Softbank and Koto are just a few funds from a large group of hedge funds and mixed funds that “rediscovered” the technology industry in the Corona years, after the decline in public company returns and an increase in private company returns. These funds, which usually own a hedge fund that invests in a public company and another fund that invests in private companies, envied the return achieved by venture capital managers – and took advantage of the low interest rates and cheap money of the Corona years to invest hundreds of millions of dollars at once in huge companies, according to a value of billions.

These funds were also accused of inflating the value of companies: the large sums they showered on the entrepreneurs and companies did not give them control, but rather a relatively small share of the shares – which in turn artificially increased the value of the company. Tiger Global, for example, does not own more than 15% of an Israeli company.

Now, with the increases in interest rates, the declines in the capital market, and the bursting of the company value bubble alongside the withdrawal from China as a producer or as a consumer market – portfolio companies of many funds are causing a tremendous loss of value. Softbank, for example, suffered a lot from the Dordash IPO that was issued at the end of 2020 – and since then its share has dropped by 73%. The cancellation of the acquisition of chip company ARM by Nvidia for 40 billion dollars earlier this year was also a big blow to the Japanese fund. Tiger Global also suffered from the declines in the public markets, including promising stocks that failed such as Zoom, Robin Hood and DocSyn. It was forced to reduce its exposure to declining stocks such as DoorDash, Coinbase and Carbna.

“Tiger, Koto and their ilk did not disappear, they simply returned to where they came from: investments in public companies. Where today, after all the declines, it is possible to beat the banks in the ability to achieve a large return,” says one senior investor. Another investor we spoke with actually welcomes the exit of the giant funds from the growth company market. “There is no justification for rapid investments like those made here in the last two years,” says the investor. “Before investing, you have to meet the company over the years at different points in time and develop a long relationship with the entrepreneurs. You cannot meet the entrepreneur for the first time, at the same meeting where they offer him an investment agreement. You have to get to know the company over the years at different points in time and develop a long relationship with The entrepreneurs. In many ways, we are now returning to the situation we were in a year and a half ago – a market dominated by Israeli investors, and in which American investors work in cooperation – without throwing money at the entrepreneurs.”