This Thursday, the remains of Gonzalo Queipo de Llano were removed from the Basilica of the Macarena in Seville, during the early hours, in the presence of his family. Thus ends a controversy that has lasted for years. In 2009, in fact, references to his status as lieutenant general and the date of the coup were already removed from the tomb. A month ago, the Government of Pedro Sánchez finally asked the Brotherhood of Hope Macarena to exhume his remains, those of his wife and those of Francisco Bohórquez Vecina, in compliance with article 38.3 of the Democratic Memory Law.

The body of the Francoist general who led the coup d’état and the subsequent repression in the Andalusian capital left the basilica at 2:20 in the morning. The works have been produced amid the applause of their descendants, all dressed in rigorous mourning, while a woman shouted and alone recited the names and surnames of some reprisals by Queipo de Llano. According to calculations recently made by nine universities in Andalusia, there were 45,500 executed in the Southern Military Region.

The general is credited with 14,000 civilians in Seville alone, of which 3,000 would have been killed in the first quarter of the war. Queipo de Llano also participated in the so-called ‘Desbandá’, that massacre of another 5,000 people who fled from Malaga to Almería in February 1937 and of which he himself raised his chest in his famous harangues on Radio Sevilla: “Red scoundrel from Malaga… Wait for it to arrive in ten days! I’ll sit in a cafe on Calle Larios drinking beer and, for every sip I take, ten will fall. I’ll shoot ten for every one of ours you shoot, even if I have to drag you out of the grave to do it.”

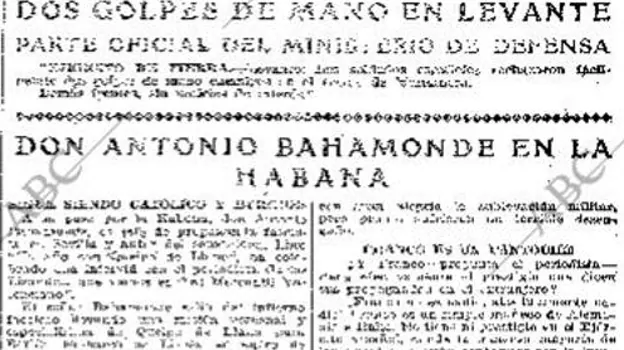

His speeches on the airwaves were so brutal – «Haven’t the communists and anarchists been playing free love? Now at least they will know what real men are and not fagot militiamen. They are not going to get rid of it no matter how much they struggle and kick” – that even some of those who supported him in the military rebellion in Seville ended up confronting Queipo de Llano and abandoning the fight against the Republic. That was the case of none other than the Propaganda delegate of the Francoist government in Seville, Antonio Bahamonde, who was under the direct orders of the feared general.

“They go to mass in the morning”

This is how he explained the reasons for his desertion in an interview granted to ABC Republicano, in December 1938: «My departure from rebellious Spain was not motivated by ideological questions, but by a problem of conscience. I left horrified at the crimes that were being committed there. It is something that someone who has not lived in rebel territory cannot even have an idea of. Dread doing calculations. Until the moment I embarked, those shot amounted to the frightening figure of 150,000 only in Andalusia and Badajoz. The most monstrous thing is that the Falangist leaders who are in charge of repression are blessed by the clergy. They go to mass in the morning, receive communion with great anointing and leave the church to continue their macabre work».

Although it may seem so, Bahamonde was not a socialist deputy or a communist leader, but a convinced Francoist who had voluntarily applied for his position alongside Queipo. A position that he had taken convinced that he had to put an end to the crimes of the Republic against the Church, but which he reneged on shortly after seeing, as he said, “how men who dare to have patriotic ideas are coldly assassinated, without matter whether they are right-wing, Catholic or monarchist.

Bahamonde was born in Madrid in 1894 or 1896. It is not very clear. The data that exists about him is what he himself revealed in his interview with ABC and in two books he published. The first, ‘A year with Queipo. Diary of a nationalist ‘(Spanish Editions, 1938), he published it when leaving Spain, although before the end of the Civil War. In it he charged against the violence exerted by Queipo de Llano in Seville, under whose orders he had been until January 1938, and was reissued by the publishing house Espuela de Plata in 2005. The second, a collective work published in exile, in 1940, whose title was ‘Mexico is like this’.

Apart from this, the annotations that appear in the Historical Memory Documentation Center and the General Archive of the Administration are merely anecdotal. According to Moisés Domínguez, in the military archives of Ávila, Segovia and Guadalajara he does not appear mentioned either. The various investigations carried out by this historian in various institutions, local archives and other records were equally unsuccessful. He alone found some loose data in foreign archives or newspaper libraries.

Queipo de Llano, in one of his speeches from Radio Sevilla

Flight from Spain

In the ABC interview, conducted in Havana, Bahamonde acknowledged that he had fled to the Cuban capital after Queipo de Llano ordered him to travel to Berlin on a mission. The ship on which he had boarded in Lisbon called at Rotterdam, from where he escaped ‘to tell the world of the horrors he had witnessed’. In his explanations, however, he warned: «I want you to say that I am still a bourgeois and that my ideas are very moderate. I have always been a Catholic and I still am, despite the fact that my faith has suffered terrible tests due to the crimes that I have seen committed in the name of religion. […]. It is impossible for a man of conscience to justify the massacres organized by people who practice murder by invoking God».

In his book, Bahamondes analyzed the role of the Falange and that of the clergy, recounted how the rebellion had taken place in Andalusia and how the Francoists, whom he had initially taken as comrades, used “defamation” as if they were a weapon. more it was about. Chapter seven began as follows: «In the territory under the command of the ‘liberator’ of Andalusia, the infinite provisions dictated by Franco and his clique to seize the property of others do not apply at all. Don Gonzalo de Sevilla has seized all the property belonging to people who have been shot […]. Poverty that no one dares to remedy, for fear of being branded a Marxist. Falange, with its social assistance, gives a ranch to its victims, forcing children to wear the blue shirt of their parents’ murderers.

The most critical chapter of all those included in his book is the one that refers to ‘The repression‘, in which he details: «The cruelty of this war is unprecedented in history. The victims made in the rear far outnumber those killed on the battlefields. Thousands of victims of all classes, of all professions and of all ages have been immolated. Queipo had to give an order so that minors under 15 years of age would not be shot. At first, thousands of people were killed where they were found, many on the doorstep of their own homes. They have shot from exemplary priests, to platonic anarchists, doctors, professors, teachers, industrialists, workers, etc. There is only one mobile: terror. Terror, as the only weapon to achieve victory.

Bahamonde interview, on ABC, December 14, 1938

“A writ of war”

In the introduction to the reissue of ‘A year with Queipo’, the historian Alfonso Lazo believes that Bahamonde’s book should not be taken as a piece of research, despite the accuracy of the data it provides, but as a work of propaganda in favor of the Republican side: “A pure and simple war document, where all the criminals are on one side and the victims on the other, but also a true document of the atrocious massacre that was taking place in the territories controlled by Queipo. A document that, even so, must be placed in parallel with other eyewitness documents where the other atrocities are collected, that is, the crimes, not minor ones, committed on the Republican side.

Queipo de Llano justified his repression by the fact that he had very few people to revolt in Seville and, as he occupied towns in Seville and Andalusia, he could not afford to leave potential enemies alive who could attack him later. That excuse, however, could be valid in the first weeks of the Civil War, when he attacked the Republicans in his incendiary radio threats, but not later, when the Francoist side had the help of Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy. in the form of planes, tanks, submarines and well-trained soldiers.