Most Italian Jews supported the fascist regime’s conservative politics and its imperialist ambitions in Africa. Benito Mussolini, in 1938

In 1516, the Venetian authorities decided to assign Jews a separate neighborhood near the new foundry (Ghetto Nuovo, in Italian). It was the first ghetto on European soil; In the years to come, Jews will be concentrated in many more ghettos across the continent.

The last remaining ancient ghetto in Europe (before the renewal of the ghettos by the Germans in World War II) was also located in Italy – the Roma Ghetto. It was “cancelled” in 1870. In this year, the process of equalizing the rights of Italian Jews that began with their emancipation, in 1848, was completed.

The sharp and rapid positive change in the status of the Jews progressed simultaneously and subject to the process of the liberation and unification of Italy. Not only that, as Italy grew stronger, their situation improved. Their representation in parliament, in liberal professions, in senior officers and in the upper class was at the beginning of the twentieth century above and beyond their proportion in the population.

Italian Jews recognized the connection between the two things, and naturally they became passionate Italian patriots – to the point of idealizing Italy, which did not diminish and perhaps even increased during the Fascist period.

With the rise to power of Benito Mussolini in 1922 and the following years, only a few in the Jewish community opposed fascism; The majority supported the regime’s conservative politics and its imperialist ambitions in Africa.

Looking back, historian Shira Klein writes in her in-depth and myth-busting book “Italian Jews from Emancipation to Fascism”, published by Cambridge University Press in 2018, there is reason to question this approach. Economic analysis can attribute the success of the Jews to market forces, not to the state.

Classical anti-Semitism continued to be prevalent in Catholic Italy (although, unlike other European countries, no anti-Semitic party arose in Italy. This can be attributed to the relative smallness of the community, and the low proportion of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe who joined it; to illustrate: in the East End of London at the beginning of the twentieth century, more than – 60 thousand Jews from Eastern Europe – more than the entire Jewry of Italy). Fascism admittedly tolerated the Jews, but did not treat them as equals.

Not only that – Italian colonialism claimed more than a hundred thousand victims in Africa through the use of gas, the establishment of concentration camps, sexual abuse, racism and transportation. Italy’s war crimes in Ethiopia, Eritrea and Libya should have warned the Jews of the regime’s inherent racism long before the 1938 race laws.

But in reality, of course, writes Klein (who is based on hundreds of diaries, memorabilia and interviews), things looked different to the Jews. They compared their lives in modern Italy to their lives before, in the ghettos, and felt lucky. The same is true when they compared their quality of life to that of other Italians, certainly when they compared their situation to that of their brothers, the Eastern European Jews. They enjoyed cultural and economic prosperity.

In the background, revolutionary socialism threatened the good order of the post-World War I era. Even if the fascist government did not see the Jews as truly equal citizens, they supported – as members of the middle-upper class – its anti-socialist approach, and enjoyed the fruits of colonialism in Africa.

Looking back, the concept of fascism is associated with racism, suppression of civil and human rights, unlimited power of the state and the perfume of Ayelet Shaked. In real time, fascism seemed to the Italian Jews to be the preferred alternative among the existing ones, and Mussolini was seen as a symbol of stability, discipline and progress.

The fact that Mussolini had a Jewish lover (a French Margherita), his public statements against racism, his positive attitude towards Zionism (and at the same time – the positive attitude of elements in the revisionist movement towards him), all these contributed to the pro-fascist position of Italian Jewry.

Here it is appropriate to point out that the tendency of the Jews as a community (as opposed to individual revolutionaries) to prefer the patronage and protection of the authorities was not unique to the time or place. Historian Yosef Haim Yerushalmi defined the connection of Jews to the countries in which they spread around the world and their rulers a “vertical connection”, we were subordinate to the government, as opposed to a “horizontal connection”, that is, a connection with the other elements of the population.

The government is seen as a sponsor, while the surrounding society is a possible source of catastrophes. Or in the words of Tractate Avot, “O pray for the peace of the kingdom.” This was true in the pre-modern world, and remains true in modern times as well, even if sometimes in other ways and in different configurations.

The Jewish fascists were forgotten

Ninety years passed from the emancipation of Italian Jews in 1948 to the racial laws of 1938. Their patriotism starting in the mid-19th century paved the way for the trust they continued to give in Italy. They convinced themselves that the fascist government did not really want to harm the Jews, that the racial laws were a constraint of the alliance with Hitler.

Even after 22% of the 45 thousand Italian Jews were murdered in the Holocaust, Jewish refugees in America continued to describe Italy as a victim. Indeed, the extermination of the Jews only began after the Nazi occupation in 1943; Indeed, there were Italians who saved Jews. But the reason for the low rate of deaths was the chronological proximity to the end of the war, the geographical proximity to the liberated South and neutral Switzerland, and the chaos of the civil war – not necessarily philosophies.

With the end of World War, the myth of Brava gente, “Italians are good people” was born. Klein claims that the Jewish victims of fascism played a part in establishing the myth: the survivors emphasized the part of the rescuers and not the persecutors. They tended to praise Italy for its conduct during World War II.

In Klein’s estimation, this was pragmatic thinking, designed to allow them to continue to feel at home in Italy. It should not be forgotten that this is one of the oldest Jewish communities, outside the Land of Israel, more than 2,200 years old, and its connection to the Emek place.

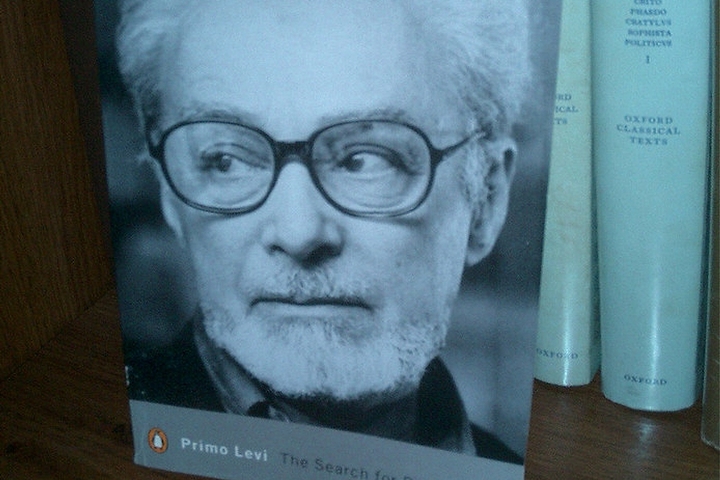

Meanwhile, the horrors of the Holocaust in the rest of Europe, and the fact that Italian anti-Semitism was seen as a cheap imitation of German racism, helped to dwarf the attitude of the fascist regime towards the Jews. The position of the Italian Jews on the eve of the war was also forgotten. The writer Primo Levi – who tried to join the anti-fascist underground, was captured and sent to Auschwitz – is seen as representative. The Jewish fascists – the infinitely many – were forgotten.

is seen as representative. Primo Levy on the cover of the book “The Search for Roots” (Photo: Alfred Essa, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Italy itself, of course, had an interest in cultivating the narrative of the good Italian, out of an aspiration to integrate into the Western Bloc – and the allies who liberated Italy also had a similar interest.

Along with the persecution of the Jews in Italy and Libya that was under its rule, the Italian army committed war crimes in occupied Yugoslavia, Albania and Greece, including the establishment of concentration camps, the massacre of civilians and the elimination of hostages. Postwar Italian authorities avoided prosecuting the war criminals responsible. Here, too, the Italian policy served the interests of the allies, the United States and Great Britain, who feared a communist takeover and preferred industrial peace.

It is not surprising, of course, that the Italians themselves promoted a glorified historiography of enlightened colonialism in Africa, enlightened occupation in Greece and Yugoslavia, and popular support of the Italian people for the partisans during the Nazi occupation.

But not only in Italy – until the end of the eighties of the last century, the narrative of the good Italian was also accepted in the historical research for no reason, and was perceived as a solid fact. For example, in her book “Eichmann in Jerusalem”, Hannah Arendt writes that even staunch Italian anti-Semites did not take the racial laws seriously, that they did not apply to the majority of Jews, and that “Italian humanity” meant that the anti-Jewish measures were not popular.

One researcher wrote about the “philosophy” of the Italians. Another about their solidarity with the Jews, and another researcher about their “immunity from racism”. Another noted that “in Italy there was no racism, and anti-Semitism had no tradition of its own. The racial laws had a different and more ‘civilized’ character” since Italy “applied the racial laws in a limited way and sometimes imposed procedural limitations on them in favor of the Jews.”

As mentioned, the research has developed since then, and in her book, Klein provides many examples of a different approach. But myths have a life of their own, as does turning a blind eye to fascism and racism. To illustrate: thousands of people are exposed to Wikipedia entries every day, less to historical articles and research. As of today, the English Wikipedia entry on the 1938 race laws states that “they were unpopular among Italian citizens”.

You might be interested