X-ray technology and tomography have proven to be increasingly useful technologies in medical and scientific research. Recently, experts from Kurashiki University have used them to examine a mermaid mummy, barely 30 cm, guarded and venerated by the monks of the Enjuin temple in Asaguchi, in Okayama prefecture, in Japan.

The monks say that a fisherman found it, and inside the wooden box that serves as a sarcophagus there was a note stating that it was “a mermaid caught in a net in the sea off Tosa […] in the Genbun era (1736-1741)”.

The results of the autopsy

The results of the investigation reveal that the object’s creation likely took place in the late 19th century, some 100 years after the note claims. Its hair is from a mammal, although the species could not be identified.

Pufferfish skin was used to cover the arms, neck, shoulders, and cheeks. For their nails they used animal keratin. The lower half of the small body, the tail, is a mixture of fishbones, possibly from a tail or dorsal fin. The jaw and teeth belonged to a carnivorous fish. We could say that the torso is that of a puppet. They shaped it using cloth, paper and cotton.

Kurashiki University of Science and the Arts, CC BY

the mermaid keepers

Several museums and private collections keep objects registered as Fijian mermen or mermen and gather countless artifacts and mummies, many of them half-fish, half-monkey, who were once treated as genuine mermaids. Some examples are in the British Museum or the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden. For the most part, its origin is linked to Asia and, specifically, to Japan.

Thus, the Enjuin mummy is not a unique case.

Barnum’s Fiji mermaid mummy is held at the Peabody Museum of Archeology and Ethnology at Harvard University, while the mermaid from the Buxton Museum and the mermaid from the Horniman Museum in London are considered treasured objects.

Horniman Museum & Gardens

The Horniman museum mermaid was also studied in depth. The results of an extensive analysis were published in 2014. They then found traces of metal, wood, rope, mud and textiles in the composition of the mummy NH.82.5.223. Wood sections were nailed perpendicular to create the torso and shoulders. The neck was built in one piece and snapped into the torso. The scan also showed two bamboo sticks inserted for arms, and wire was used for the spine.

In addition to museums, mermaid mummies are still kept at Shinto and Buddhist shrines in Japan, such as the mermaid o ningyo del santuario Tenshou-Kyousha cerca del monte Fuji.

A universal myth

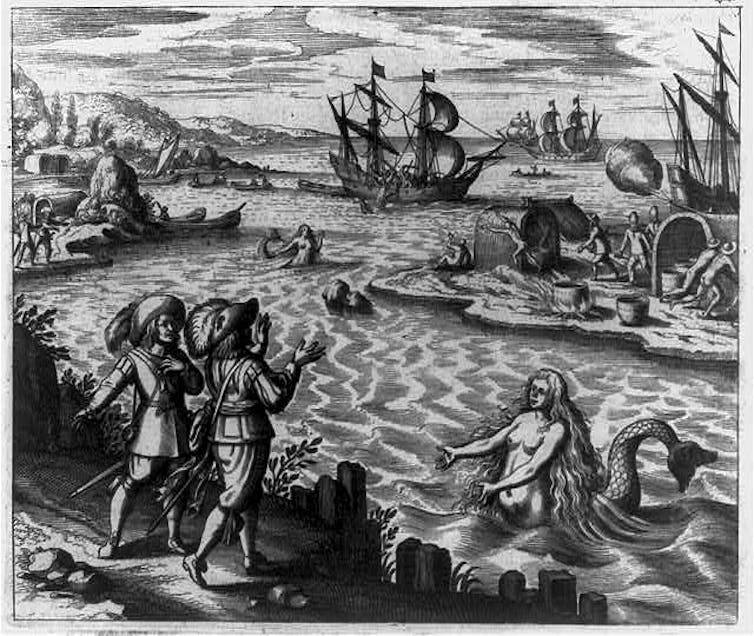

These sea creatures have been represented in the mythology of different cultures for millennia. From Syria, with the sea goddess Atargatis, or ancient Greece, with the god Triton or Ulysses, capable of resisting her song, to the Australian aboriginal spirit of the Yawkyawk, references to benevolent or malevolent sirens are found in countless legends.

National Museum of Australia

Although the myth is universal, most of the mermaid mummies preserved in temples and museums are Asian, mainly Japanese. And most of the mermaid mummies studied at the beginning of the 19th century and made in Japan are presented in a painful pose, twisting on their tails and with their hands on their faces as if they were screaming.

British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA

meeting with a mermaid

It was on the island of Dejima, in Nagasaki Bay, that they first came to the attention of European travelers.

In the 1920s, stories such as that of a fisherman who caught one of these mermaids are collected. She, as she died, predicted a time of great prosperity, but one that was accompanied by a fatal epidemic.

Library of Congresss, CC BY

The momomania of the XIX

The practice of mummification has fascinated the curious since ancient times. The preservation of the body through dissecting, evisceration and the use of resins and other spices has been recounted for posterity by Herodotus or Diodorus Siculus, in the case of ancient Egypt. the term itself mummy derives from Persian mummy to refer to bitumen.

As revealed by the archaeologist from University College London Gabriel Moshenska, this material was very precious in 11th century Persia.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the use of mummies for medicinal purposes gave rise to an international illicit market in Europe, raising the question of their treatment as objects and the appearance of forgeries.

The Renaissance and the growing interest in mummies led to fragments and mummified bodies beginning to appear in European museums in Dresden, Milan, and Leiden. Catherine de’ Medici even sent an expedition in 1549 to the Saqqara necropolis, in Egypt, to extract mummies for medicinal purposes.

F.W. Geurin / Library of Congresss

The mummies acquired incalculable value since Napoleon’s campaigns in Egypt (1798-1801), although they reached their zenith of popularity during the 19th century. The Romanticism movement reinforced the passion and taste of scholars and writers for exoticism. At the same time, anatomical studies and mummy autopsies proliferated at this time.

Thus, explorers, travelers and adventurers began to acquire mummies. Patrons created private collections and museums also took possession of them. Falsifying them became a lucrative business and the stories of sailors and fishermen about mermaid mummies and sightings of these creatures spread throughout the world. Thanks to their great popularity they have been a true and mysterious object of study for centuries.