2024-09-15 11:03:35

After almost thirty years of hesitation by his predecessors, the Minister of Culture Martin Baxa from the ODS pushed through a law that allows the establishment of so-called public cultural institutions. Although it is a compromise variant, it nevertheless offers a different operating model than the existing contribution organizations, such as the National Theatre, the Czech Philharmonic or the National Gallery. But will there be interest in the transition to the new rules?

Talk of a public legal or public cultural institution began shortly after November 1989. It was obvious that the cumbersome legal form of a subsidized organization dating back to the days of socialist cultural management was not suitable for theaters, galleries, museums or orchestras established by the state or cities in the free, “market” the environment is far from ideal.

The current model gives politicians at the town hall or the Ministry of Culture the opportunity to fire and appoint heads of important institutions from day to day without giving a reason and thus practically subvert them, as we have experienced at the national and regional level, for example with the dismissals of Ondřej Černý from the management of the National Theater and Jiří Fajt from the National Gallery. However, even the very operation of the “contribution card” is subject to inflexible salary tables, not entirely rational economic rules and annual political decision-making on the amount of the subsidy.

Running a national theater or a regional gallery means, with a slight exaggeration, often not knowing in December how much money I will have for operations in January. This is also why it is often difficult to find capable directors endowed with vision, invention, experience and managerial skills, who would come to terms with the fact that the fate of themselves and the institution can be influenced by any political whim more than the professional level of work.

The longer this state of affairs lasted, the more practice showed what the law introducing the new legal personality should correct. On the contrary, politicians did not rush into the change too much and mostly showed that they were quite comfortable with the system of contributory organizations. With the only exception, and that is the possibility of so-called co-establishment – especially the cities sometimes reported that they would like to share the responsibility and expenses for their theaters or orchestras with the regions. It was even more complicated with the desire for change among some employees, especially members of collective bodies such as theater orchestras and choirs. They preferred the certainty of tabular salaries and resisted the change through the unions. And in all of this there were opinions that the main problem of culture is not the absence of a new law, but simply a lack of money.

Money comes first

Now it is done, the law promoted by the Minister of Culture Martin Baxa from the ODS has already been signed by President Petr Pavel. From 2025, public cultural institutions will be able to establish either the state directly, or cities and regions. If they choose voluntarily, they can also transform an existing contribution organization into a public cultural institution, but this is not mandatory.

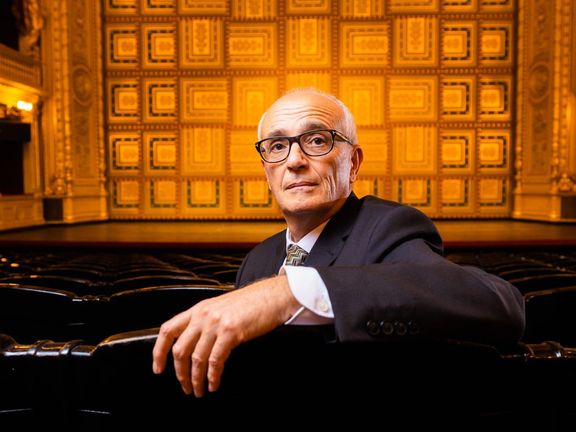

The new law could come in handy for the National Theater in Brno, which is run by Martin Glaser (pictured). | Photo: Josef Kubíček

A novelty is the option where, for example, a theater or a gallery would be founded jointly by the city and the region. The law envisages multi-year funding, so the representatives of both parties must also clearly agree on how they will share the budget, up to four years in advance. The state can then support the activities of a public cultural institution with two or more founders and also commit to financial subsidies for several years by contract. Cities and regions can do the same to a public cultural institution established by the state.

Example: the artistic significance, as well as the structure of the visitors of the National Theater Brno, which has a drama, opera and ballet troupe and loudly supported the new law, goes far beyond the borders of the city. At the same time, the Brno Town Hall and the South Moravian Region contribute about half a billion crowns to its budget of roughly 600 million crowns a year. The ideal solution could be to transform it into a public cultural institution, where the costs would be shared by Brno and the region, perhaps in a ratio of three to one. And contractual support from the state.

On the other hand, he is now establishing the Prague National Theatre, which at the same time provides a cultural service primarily to the people of Prague. After its eventual transformation into a public cultural institution, he could call on the municipality of the metropolis to contribute at least a tenth of the funding.

Both options for co-financing, which are supposed to ensure the stability of cultural organizations and “more fairly” distribute the burden on individual budgets, seem to be logical and formally well resolved in the law. However, the question is the motivation of the new co-founders to introduce such a model when they don’t have to.

Will they voluntarily commit themselves to considerable expenses and, in fact, to co-responsibility just for the good feeling of “investing” in culture or the possibility of sending their representatives to the board of directors? Enlightened interest cannot be assumed automatically, and the current political composition of city and regional councils will always have an influence, which will change the elections in less than 14 days.

If the Prague National Theater led by Jan Burian (pictured) used the new law, the capital could participate in its financing. | Photo: Tomáš Nosil

Will the Board of Trustees sort this out?

The guarantee that the public cultural institution will be relatively independent of politicians should be provided by the establishment of administrative boards, in addition to the resolved financing. To a large extent, they will take over the powers and responsibilities that the founder has in current contributory organizations. They will appoint and dismiss the director, conclude a contract with him, discuss the institution’s financial plan, financial statements or annual reports, but also comment on the overall direction and program.

Matters entrusted to the board of directors can be specified and supplemented by the charter, where the law conveniently leaves a relatively large space to adapt the rules “tailored” to the given gallery, theater or orchestra. In addition to the financing method, the number of members of the board of directors, the length of their mandates, the method of selecting the director or the form of the control body can be set here.

From the point of view of the professional public or employees, the third of the members of the board of directors, which should ensure their influence, will probably be the most important. It must be appointed on the proposal of so-called persons with the right to nominate, which can be various professional associations or persons active in culture, science or education.

The minister was able to rely on the experience of the boards of directors, which are already active in some grant-making organizations, but rather fulfill the function of an advisory body to the director, and their responsibility is purely informal – this applies in particular to the so-called guarantee boards of the National Gallery and the National Theatre.

Both rely on the authority of public figures or donors, but they have already proven themselves in crisis situations. If it were not for the guarantee council, ex-minister Antonín Staněk from the ČSSD would have had a free way to dismiss the director of the National Theater, Jan Burian, a few years ago. He could have done it as smoothly as in neighboring Slovakia, where the Minister of Culture recently fired the heads of the National Theater and the National Gallery for a day.

Board members will have strong powers as well as responsibilities. They should thus understand not only the professional or artistic profile of the institution, but also its internal operation and economy. And above all, they should be able to reach consensus among themselves, the director and the founder. So that incompetent politicians interfering in the running of theaters or galleries do not replace administrative boards, in which representatives of regions, cities, the professional public and employees will argue.

In any case, this new form of supervision will be demanding on communication. Until now, the director negotiated his plans and budget directly with the Minister of Culture or his officials. Now he will have to convince three, six, nine or more members – the number must be divisible by three – of the board, representing different subjects and interests. It will probably be demanding in terms of time, and it probably won’t work without a financial reward, especially if the members of the board of directors have material responsibilities as well.

And again, the question arises: will politicians, who would lose their powers and the ability to influence their operation by transforming their contribution organizations into public cultural institutions, want to give it up voluntarily?

The establishment of administrative boards can prevent political interference in cultural institutions, such as when the head of the National Theater Ondřej Černý (center) was dismissed in 2012. | Photo: Jiří Koťátko

What the law is silent about

One of the arguments against the adoption of the law, which was repeatedly voiced for decades, was the fear that the “independence” of cultural institutions may mean a risk for the alienation of property, especially museum and gallery collections, but also heritage-protected objects that would be managed by a public cultural institution.

The adopted law dispelled such concerns with the possibility to specify in the deed of incorporation protected property that cannot be alienated or encumbered, except with the consent of the founder. Cultural monuments, museum collections or library funds fall under this protection automatically.

However, the law encountered the greatest resistance every time when it came to an attempt to relax the rules for remuneration of employees and to replace tabular salaries, which have been deeply below average in cultural contribution organizations for a long time, with contractual wages.

Now, when theater directors want to decently pay the actors who make up the repertoire, or if the head of the opera and ballet wants to offer an appropriate fee to a visiting foreign star, they run into countless obstacles. On the other hand, it is equally difficult to make it clear to a member of the orchestra who fulfills his duties “lukewarmly” during remuneration that he could look for another job.

The heads of large theaters in particular pinned their hopes on the fact that the new legal form would enable a more flexible solution. However, Minister Martin Baxa apparently left the solution of this problem completely out of the law for good reasons. Table salaries therefore remain. On the 24 pages of the law, only two paragraphs added by the Chamber of Deputies in the second reading are devoted to labor relations. The first one determines when a member of the artistic ensemble should be present at the workplace, the second one adds that if the person in question arranges work outside of this time, they cover the costs associated with it. Considering the absence of fundamental rules, this trifle seems almost funny. But it is probably a compromise, without which the law would have no chance of passing.

It is great that Minister Bax managed to push the change through Parliament and complete a task that his predecessors were either not good enough for or did not consider important. This form of a public cultural institution that balances specific conditions for artistic creation and cultural heritage management, a certain independence from the founders and the possibility to function flexibly and economically rationally has been sought for a long time. The ministry finally found inspiration in the Act on Public Research Institutions. But lessons could also be learned from Germany and Austria, where public theaters, galleries and museums founded as companies, headed by managers appointed by boards of directors, have been functioning well for years.

The Public Cultural Institution Act is not perfect and does not solve all issues. When theaters, galleries or orchestras gain experience with the new model, it will always be possible to supplement or change it. It is an opportunity for culture and a call to courage for politicians.

Video: When choosing guests, Czech television should not judge who attacks the state’s values. Others decide that, says Souček (September 7, 2024)

According to the director, Jan Souček, public television should give space to everyone, including those whom someone calls anti-system. He said this on Spotlight. | Video: Team Spotlight