2024-07-28 16:28:38

Something similar to a gold rush is happening in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. The race to obtain minerals from the bottom of the sea, deep-sea mining. Korea is one of the countries that has jumped into exploration to secure minerals from the sea early on. What if our country could mine and use the cobalt, nickel, manganese, and copper buried deep in the sea? It’s quite an exciting story.

However, deep-sea mining is a very divisive topic, with both pros and cons being extremely divided. The opposition voices were further strengthened a few days ago by new research results showing that seabed minerals create oxygen in the ocean. It is a topic that is bound to become more and more controversial in the future. Deep Sea MiningLet’s take a look.

*This article is the online version of the Deep Dive newsletter published on the 26th. Subscribe to Deep Dive, the ‘economic news you’ll get hooked on as you read’ newsletter.

Treasures stuck in the sea floor

Before the explanation, let’s dive deep into the ocean. This is the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ) in the Pacific Ocean southeast of Hawaii. The depth is about 4,000 meters. It is usually dark and deep, but when you shine a light, it becomes salty. This kind of scenery unfolds.

![Deep Sea Mining Controversy: Oxygen-Emitting Minerals Under the Sea[딥다이브] Deep Sea Mining Controversy: Oxygen-Emitting Minerals Under the Sea[딥다이브]](https://dimg.donga.com/wps/NEWS/IMAGE/2024/07/26/126142230.1.jpg)

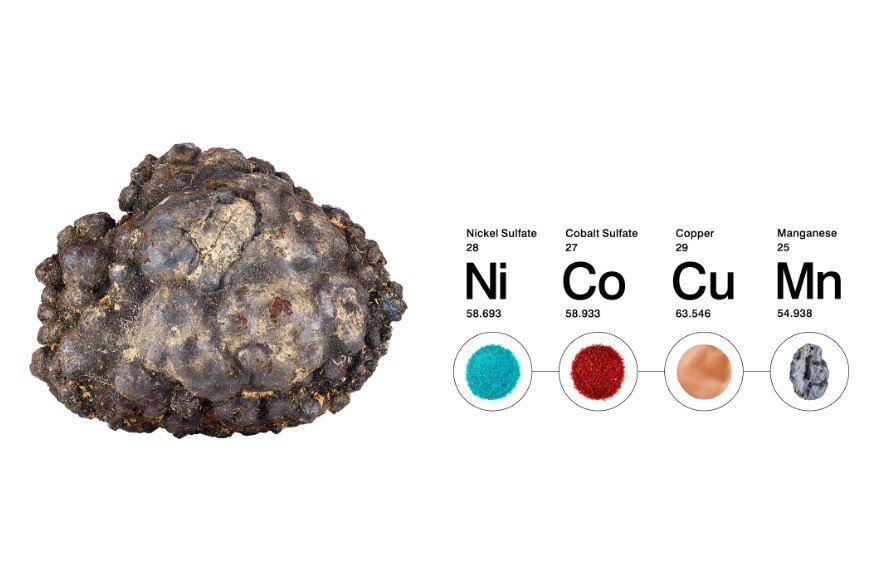

What does it look like? It looks like a rock field with rocks that look like potatoes stuck in there. This is Nodaji. These precious manganese nodules are everywhere. The main components of manganese nodules are nickel, manganese, copper, and cobalt. They are important metal resources used in electric car batteries, wind turbines, and solar panels. Over millions of years, these elements have accumulated to form lumps that are 5 to 10 cm in diameter.

How many manganese nodules, which are like treasures, are buried in the ocean? Let’s look at the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ), which is almost as wide as the continental United States. According to recent estimates, About 7.5 billion tons of manganese, 3.4 billion tons of nickel, 78 million tons of cobalt, and 275 million tons of copper.It includes manganese. I was curious, so I compared it with the U.S. Geological Survey data. It means that manganese is five times the world’s onshore reserves, cobalt nine times, and nickel three times. Copper is one-eighth of the proven onshore reserves.

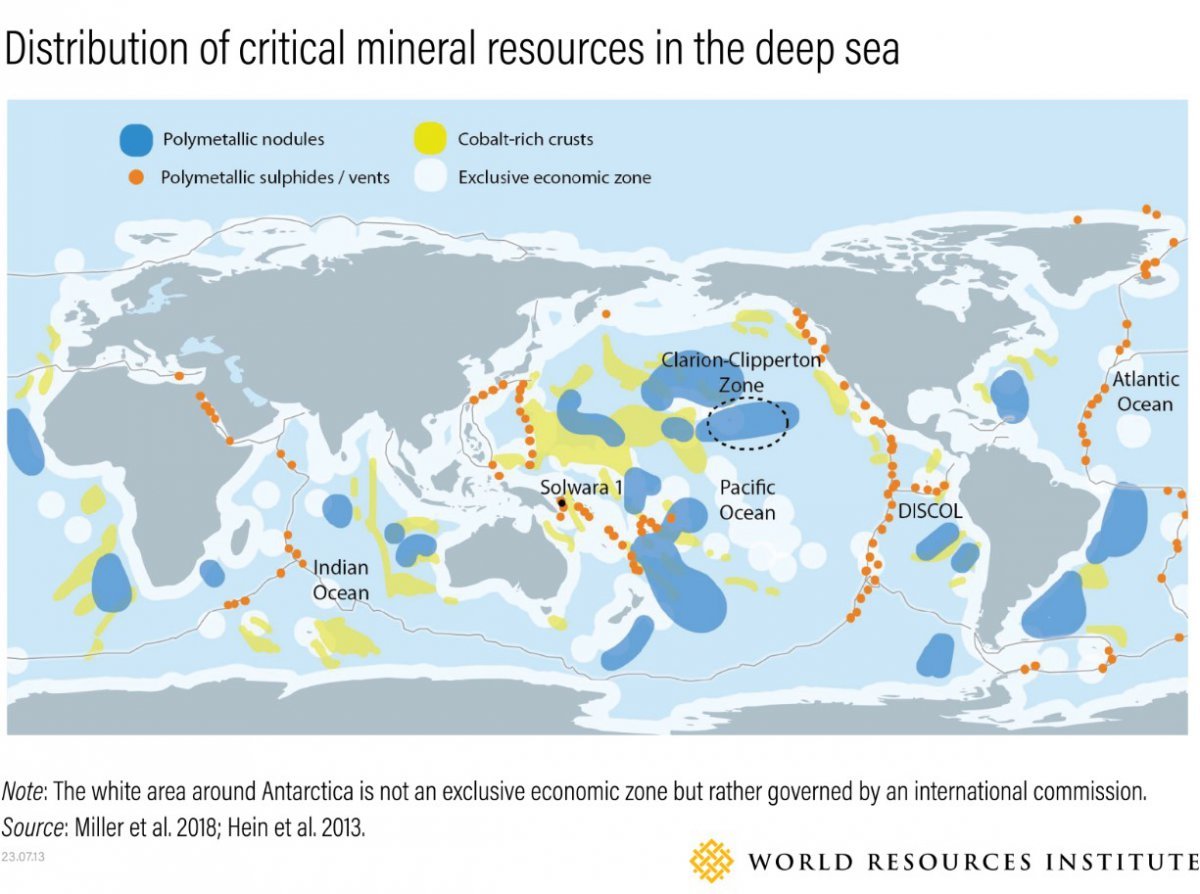

There is not only one place like this in the vast ocean. Please refer to the map below. The area marked in dark blue is the area where manganese nodule fields are spread out on the seabed. It feels like looking at a treasure map.

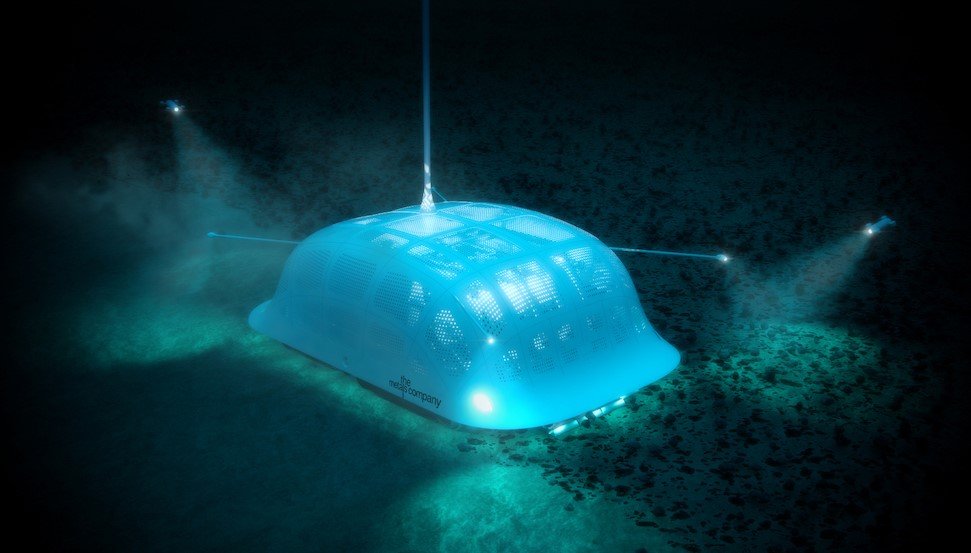

And there are other types of ores in the deep sea. ‘High cobalt manganese shell’(Yellow mark) It contains not only cobalt but also vanadium, molybdenum, and platinum. ‘Seafloor hydrothermal deposit’(Orange Marked) is a mixture of copper, lead, zinc, gold, and silver ore. They are scattered in different areas as indicated on the map. As a side note, manganese nodules can be swept up with equipment that looks like a tractor plowing a field. High-cobalt manganese nodules and hydrothermal deposits on the seafloor are so large that they have to be broken up to be mined.

Commercial mining as early as next year?

So, let’s go out to the sea and dig for ore? If we go mining within the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) where sovereignty extends, then it’s possible. Norway is currently the first country in the world to pursue commercial deep-sea mining within its EEZ. However, if you want to mine deep-sea anywhere else, you need permission. The International Seabed Authority (ISA) has that permission.

Since its establishment in 1994, ISA has approved a total of 31 contracts for undersea mining exploration, including three contracts applied for by the Korean government. Incidentally, China has the most (five), followed by Korea and Russia (three).

It’s too early to be happy that the contract has been approved. This is only ISA’s approval for ‘exploration’ (the contract period is 15 years). Commercial mining has never been approved. In other words, you can go into the sea and look for treasure, but even if you find it, you have no right to dig it up.

The ISA is currently working on the procedures and rules for approving commercial mining (including how much fees will be charged for mining). The draft is currently being discussed at the board meeting at the ISA headquarters in Kingston, Jamaica. The goal is to have the rules in place by July 2025. In other words: Development may begin in earnest as early as next year.

However, it remains to be seen whether deep-sea mining can proceed so smoothly. Currently, within the ISA There is a fierce debate between those in favor of deep-sea mining (let’s hurry up with development) and those against it (let’s take it slow).This is it. It was divided into two sides depending on the member states’ positions.

The voices in favor are mainly from developing countries such as India, Ghana, Jamaica, Argentina, and Pacific Island countries. In particular, the South Pacific island nation of Nauru is making quite advanced plans to start commercial mining in the near future in partnership with the Canadian company The Metal Company. On the other hand, there are countries that argue that deep-sea mining should be temporarily suspended or banned. There are 24 countries including the UK, France, Germany, Sweden, Brazil, Canada, and Chile.

The two sides will go head-to-head in the upcoming vote to elect the ISA secretary-general, scheduled for next week. Will the current Secretary-General Michael Lodge, supported by the pro-EU faction, succeed in his third term, or will the challenge of Brazilian ecologist Leticia Carvalho, supported by the opposition faction, succeed? Depending on the results, the process of approving commercial mining could gain momentum or slow down, which is why the International Seabed Authority is getting some much-needed attention from around the world.

The land is harder to dig, so go to the sea.

So, let’s figure out why you’re for or against deep sea mining. You can probably guess what that means.

The biggest reason why deep sea mining is necessary is Because it is becoming increasingly difficult to obtain minerals from land.I have told you in Deep Dive that it is becoming increasingly difficult to mine copper from the ground.Deep Dive Copper Edition) The same goes for other minerals. High-quality ore deposits that can be easily mined are rapidly decreasing. We have to go deeper underground or to remote places to find ore. In a situation where demand for minerals is rapidly increasing due to electric vehicles and solar and wind power generation, a breakthrough is needed.

“We are in a very desperate situation,” Michael Lodge, executive director of the ISA, said in a CNBC interview. “We are not able to meet the mineral targets that we need with our current onshore reserves. The main factor that is driving the interest of the industry in deep-sea mining is Potential to produce greater quantities of minerals at the same or lower cost than on land because of.”

Deep-sea mining also has the advantage of being far removed from problems such as deforestation and water pollution. There is no need for local consent. Sixty years ago, American scientist John Mero wrote in his book “Mineral Resources of the Ocean,” which sparked worldwide interest in deep-sea mining: “Unlike terrestrial mining, deep-sea mineral extraction involves minimal removal of topsoil. There is less extraction waste, no social displacement, minimal production infrastructure, no need to build roads and railways to transport mine sites, no drill blasting, no acid mine drainage, and no deforestation.”

Oxygen bubbles in the ore

But is it okay to dig deep in the ocean? What on earth would happen if you dug up minerals that had been buried in the deep sea for millions of years?

It is difficult to answer this question clearly. Why? Because the deep sea is still an unknown area where even 1% has not been explored yet, and there is so much that mankind does not know. Those who oppose deep sea mining emphasize this very point. They say that if we dig without knowing what will happen, it could lead to a big problem. This is why not only environmental groups but also scientists oppose deep sea mining. Dr. Cheng Chen, a deep sea biologist at the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, said, “There are many undiscovered species in the deep sea that have abilities and functions that we cannot even imagine. We can lose them without even knowing they existed.”

And this week, a paper published in the international academic journal ‘Nature Geoscience’ has attracted the attention of the world. It is a paper titled ‘Evidence of dark oxygen production in the deep seabed’, jointly conducted by researchers from the UK, Germany, and the US. This is the first time that manganese nodules in the Clarion Clipperton area have been found to produce oxygen.

How? On the surface of the manganese nodule Electrolyzes water into hydrogen and oxygen, generating electricity of up to 0.95 V That is, manganese nodules act as a kind of catalyst that supplies oxygen to the ocean. It’s quite a surprising discovery. Photosynthetic algae aren’t the only ones that create oxygen in the ocean. However, the research team hasn’t figured out how that electricity is generated.

Manganese nodules produce oxygen? What does this mean? Andrew Sweetman, an ecologist at the Scottish Institute of Marine Science who worked on the study, says we need to identify areas where oxygen production is occurring before we start deep-sea mining. “If oxygen is produced in large quantities, (the manganese nodules) could be important to the animals living there.”This means that deep-sea mining may cause irreversible damage to the underwater ecosystem.

A debate that will probably never end

In fact, if you look at the reason why rare metals like nickel, cobalt, manganese, and copper are needed, it is ultimately to achieve carbon neutrality. They will be used in electric vehicles, batteries, wind power, and solar power generation. However, if we mine them deep in the sea for this, we might harm the marine ecosystem, which is the world’s largest carbon sink (absorbing 25% of carbon dioxide emissions). Well, it is not an easy decision.

As with most controversies, the scientific evidence provided by each proponent of deep-sea mining varies. For example, The Metal Company, which is pursuing deep-sea mining operations in the Pacific Ocean, “We saw organisms that returned to the same location a year after the mining machine passed through the seabed.”(=so the environmental impact is minimal) claim. On the other hand, marine scientists “If you pull a rock to the surface, the organisms that lived there can never return.”It’s like claiming that. It’s unclear what the absolute and objective scientific evidence is. The debate for and against seems like it will go on forever. After all, it’s the realm of politics.

Let’s reserve judgment on the pros and cons of deep-sea mining for now and think about this. If we can dramatically increase the recycling rate of metals and further develop new technologies that require less rare metals, such as sodium-ion batteries, wouldn’t we not have to go far out to sea? Or what about natural hydrogen that springs from the ground? By. Deep Dive

The world’s interest in deep-sea mining was at its peak in the 1970s. The enthusiasm that had cooled down after the metal price fell has been rekindled recently. As such, the movement against it is also growing. Let me summarize the main points.

-There are several times more rare metals buried in the ocean than on land. As it becomes difficult to secure minerals from land, interest in deep-sea mining is growing. The International Seabed Authority is working to establish rules and procedures. Commercial mining may be possible next year.

-But can we really dig them up? Recently, a research team from the US and Europe confirmed for the first time that deep-sea manganese nodules generate oxygen. They say that electricity is generated on the surface and decomposes water. This means that seafloor minerals directly affect the ecosystem.

-Is deep-sea mining an inevitable choice to reduce environmental destruction on land and move toward carbon neutrality? Or is it? more Is this an issue that needs to be approached with caution? It is difficult to judge because it is an issue with sharp pros and cons. The debate will probably become more intense.

*This article is the online version of the Deep Dive newsletter published on the 26th. Subscribe to Deep Dive, the ‘economic news you’ll get hooked on as you read’ newsletter.

Reporter Han Ae-ran [email protected]

2024-07-28 16:28:38