Most people behave exactly the opposite of what economic theory predicts. Mural in Santiago, Chile (Photo: Francisco Osorio CC BY 2.0)

In 2014, a group of scientists from Harvard and Yale universities published a fascinating study on how people make decisions about the natural world. They tested whether people would choose to share finite resources with future generations. The problem with future generations is that they cannot repay us. If we choose to give up too much financial profit in order to preserve the ecology for our grandchildren, they will not be able to repay us in the same currency – and therefore we hardly gain anything when we choose to share resources with them. In light of this, economists expected people to make the “logical” decision – to exhaust the resources in the present, and not leave anything for future generations.

But it turns out that people don’t really behave that way. The team from Harvard and Yale universities divided the experiment participants into groups, and gave each of them a share of the shared resources, which must be managed throughout the generations. They found that on average, 68% of people chose to use their share sustainably, taking only as much as the common pool could regenerate, while sacrificing potential profits so that future generations could thrive. In other words, most people behave exactly the opposite of what economic theory predicts. The problem is that the remaining 32% chose to use their share of the resources to earn a quick profit.

Over time, the selfish minority impoverishes the common pool, leaving future generations with dwindling reserves of resources. The loss grew over time: in the fourth generation, the resources were already completely used up and there was nothing left for future generations – an amazing pattern of deterioration, which is very similar to what is happening to our planet today.

>>> “People all over the world yearn, quietly, for something good from capitalism”

However, when the groups were asked to make joint decisions, through direct democracy, something amazing happened. Allegedly, those 68% could make a decision against the selfish minority and curb its destructive impulses. But in fact, democratic decision-making encouraged the selfish types to vote for more sustainable decisions, because they understood that everyone was in the same boat. Again and again, the scientists discovered that under democratic conditions, resources were preserved for future generations, at a level of 100%, for an unlimited time. The researchers carried out the experiment for a period of a dozen generations, and continued to get the same results: no depletion. is nothing.

What is amazing is that there is widespread and intuitive support for what ecological economists call “steady state” economics. A steady state economy is governed by two important principles designed to maintain a balance with the animal world: to reach a steady state economy, we need to define clear upper limits for the use of resources and waste. For decades, economists have told us that such upper bounds are impossible, because people wouldn’t think they make sense. It turns out they were wrong. When given a chance, these are exactly the policies people want.

The problem is in the political system

This helps us see our ecological crisis in a new light. It is not “human nature” that is problematic here. The problem is that we have a political system that allows a small number of people to sabotage our common future, for their benefit. How can it be? After all, most of us live in democracies—so why do real policy decisions look so different than the Harvard-Yale experiment predicts? The answer is that our “democracies” are not, in fact, that democratic. As income distribution became more and more unequal, the economic power of the richest translated directly into ever-increasing political power. The elites have succeeded in striking down our democratic system.

This can be seen most clearly in the United States, where corporations are allowed to spend unlimited amounts of money on political advertising, and there are few limits on party contributions. These measures – which are justified according to the principle of “freedom of speech” – make it difficult for politicians to win elections without direct support from corporations and billionaires, and they are pressured to conform to the policy preferences of the elites.

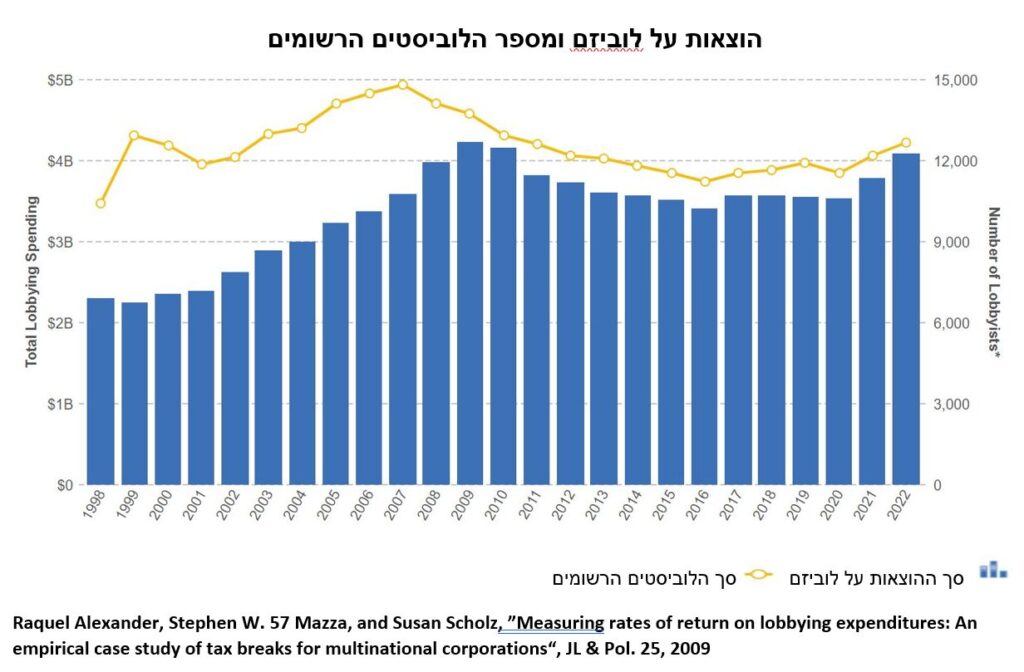

In addition, large companies and tycoons spend huge sums of money at the behest of governments. In 2010, $3.55 billion was spent on lobbying, compared to $1.45 billion in 1998. And these expenses pay off: a study found that money spent on lobbying the US Congress yielded 22,000% returns, received in the form of tax breaks and profits from preferential treatment. As a result of the political system being held captive by the elites, the interests of the economic elites in the United States are almost always favored in policymaking, even when the majority of citizens disagree with them. In this sense, the United States resembles a plutocracy more than it resembles a democracy.

In Britain there are similar tendencies, although for different (and older) reasons. The financial center and the place where most economic activity takes place in the United Kingdom, the City of London, has always been immune to many of the country’s democratic laws, and has remained free from parliamentary oversight. Voting power in the City of London Council is given not only to residents, but also to businesses. And the bigger the business, the more votes it receives, with each of the largest companies receiving 79 votes. In Parliament, the House of Lords is not filled through elections but through appointments, and 92 seats are inherited in aristocratic families, 26 are assigned to the Anglican Church and many others are “sold” to the rich in exchange for large donations to the election campaigns.

Similar plutocratic tendencies can be seen in everything related to finances. A significant part of the shareholder vote is controlled by huge mutual funds such as Vanguard and Blackrock, which have no legitimate democratic status. A small number of people decide how to use everyone else’s money, and thus have an extraordinary influence on the actions of society, pushing it to prioritize profits over social and ecological issues.

And there is also the media. In the UK: just three companies control 70% of the market, and Rupert Murdoch’s empire controls more than a third of the market. In the United States, six companies control 90% of all American media. Under these conditions it is literally impossible to have a real democratic conversation about the economy.

This is also true at the international level. The voting power in the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund – two central institutions in the management of the global economy – is disproportionately in the hands of a small number of rich countries. The Global South, home to 85% of the world’s population, has less than half of the voting power. Similar problems also exist in the World Trade Organization, where bargaining power depends on the size of the market. The world’s richest economies almost always succeed in getting their way when it comes to decisive decisions regarding the rules of the world trade system, while the voice of poorer countries – those who have the most to lose from the ecological collapse – is repeatedly not heard.

One of the reasons why we are currently on the brink of a serious ecological crisis is that our political systems have been completely corrupted. The preferences of the majority of people, who want to preserve the ecology of our planet for future generations, are trampled by a minority, elites who are perfectly happy to translate everything into profits. For our fight for a greener economy to succeed, we must try to expand democracy wherever possible.

This means kicking “big money” out of politics; to carry out a radical reform of the media; Enact strict laws regarding the financing of election systems; to deprive corporations of their status as entities; break up the monopolies; move to structures of cooperative ownership; to integrate workers into the boards of directors of companies; make shareholder voting a democratic process; democratize global governing institutions; and to manage the shared resources as common property wherever possible.

At the beginning of the book I pointed out that large audiences of people in the world doubt capitalism and yearn for something better. What would happen if we had an open democratic conversation about the kind of economy we want? What will she look like? How will it distribute the resources? Whatever form it takes, I think it’s safe to say it will be quite different from our current system, which has extreme inequality and a tyrannical obsession with endless growth. Nobody really wants this.

The barrier must be removed

For a long time we have been told that capitalism and democracy are part of the same package. But in reality, the two things really do not coincide. Capital’s obsession with endless growth at the expense of the living world is at odds with the sustainability values of most of us. When people are given the opportunity to decide on the issue, they choose to manage the economy according to the principles of the steady state, which are against the order of growth. In other words, capitalism has a tendency to be anti-democratic, and democracy has a tendency to be anti-capitalist.

It is interesting, because these two traditions grew, at least in part, from the history of Enlightenment thought. On the one hand, the Enlightenment was a search for the autonomy of reason – our right to question what is accepted, what is determined by tradition or by authority figures or by the gods. This is the core of democracy as we understand it. On the other hand, the dualistic philosophy of Enlightenment thinkers such as Bacon and Descartes cheers for the conquest of nature as the basic logic of capitalist expansion.

Ironically, these two separate Enlightenment projects cannot meet. We are forbidden to question capitalism and the conquest of nature. Such doubt is considered heresy. In other words, we are encouraged to believe in the values of independent critical thinking, but only as long as we do not question capitalism.

In a time of ecological collapse, we must remove this barrier. We must put capitalism to a critical test – of logic. The journey to the post-capitalist economy begins with the most basic democratic act.

Jason Hickel is an economic anthropologist at the Autonomous University of Barcelona and a senior fellow at the London School of Economics. (LSE). The excerpt presented here is part of his book “Less Is More”, which was published by Radical – a house for ideas. Translation: Dafna Levy; Translation editing: Tamar Neugarten; Scientific advice: Dov Hanin; Cover design: Idan Epstein