A few days ago, a news item from the Reuters agency came to the media, generating unusual excitement and expectations. It was announced that “in vitro gene editing in plants would no longer be regulated as GMOs” (GMO is the acronym for Genetically Modified Organism).

Surely many of us scientists believed that the European high court had corrected that July 2018 ruling in which it ruled that gene-edited organisms, for example with CRISPR tools, should be considered GMOs for all purposes. We put aside our traditional skepticism and wanted to believe that the blockade to gene editing in Europe was over.

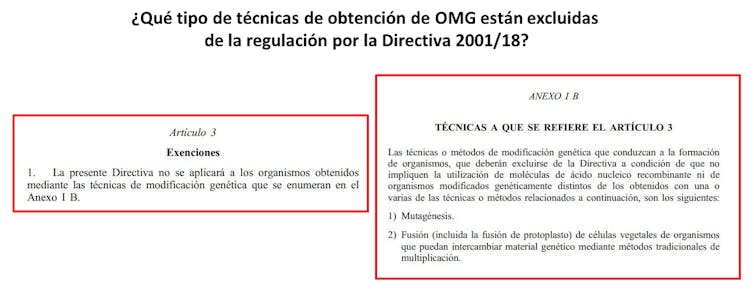

But no, the Reuters headline was incorrect. In reality, the European high court had ruled on a much lesser issue, confirming that certain types of mutagenesis (in vitro) should continue to be excluded from the regulation of the European Directive 2001/18. But without ruling on gene editing, which continues to be as blocked as before.

Europe and New Zealand remain on the sidelines

This is the penultimate chapter in an already long saga of events in which the European Union (together with New Zealand) continues not to join the majority option, which is none other than to exclude new genetic editing techniques from regulation as GMOs. like the promising CRISPR.

In plants, gene editing techniques are applied, fundamentally, to inactivate a gene and thereby achieve some improvement in the product, either in the growth of the plant, or in its adaptation to the environment. They can also be used to change (insert, delete, substitute) one or more bases in the genome, or to directly incorporate genetic variants from one variety to another. These forms of gene editing should not be classified as “genetically modified organism.”

However, if we use CRISPR tools to incorporate a new gene into the genome of the edited plant, then we would already be generating what we know as a plant. transgenicwhich would logically become regulated as a GMO.

A little history

The story behind the current blockade of gene-editing techniques to produce gene-edited plants in the EU began in 2015. It was that year when a French farmers’ union petitioned the French courts that plant varieties obtained via mutagenesis not be excluded from the regulation as GMOs (“transgenic”), as indicated in Directive 2001/18.

They were referring to cases in which plant breeders had exposed a series of plants to radiation (X-rays or Gamma rays) or chemical mutation. And then they had selected those mutant plants that produced faster, with more harvests per year or that produced larger products or with unique commercial characteristics. Both methods had been widely used to generate most of the edible varieties that we have in the supermarket today.

Well, the French justice raised the case to the High Court of the EU which, in a surprising judgment of July 2018, decreed that, although mutagenesis by radiation or chemical products was excluded from the regulation as GMOs, the new mutagenesis techniques (genetic editing) should continue to be considered GMOs and regulated like any transgenic. In other words, they equated transgenesis with CRISPR gene editing.

Author provided

Author provided

A jug of cold water for biotechnology

Said judgment of July 2018 was a tremendous jug of cold water that directly expelled from the market any biotechnological project developed in Europe and based on CRISPR that wanted to reach the European market. It should be known that in more than 20 years of application of the directive “only” a single GMO variety has been approved for cultivation in the European Union, Bt maize, transgenic, with the toxin of the bacteria Bacillus turingensisto combat the borer plague, caused by insects that attack it, which was approved in 1998.

Therefore, in Europe, when it is said “it must be regulated by Directive 2001/18” this is synonymous with initiating a risk assessment procedure against human beings and the environment that usually entails expenses of around 10 million euros for the applicant company and extend for 5 to 10 years or, as usually happens, extend without an end date.

All of this condemns any experimental proposal and sends the message that it will never be truly approved, regardless of the fact that in no case has any problem or impact on the environment or people been observed, as 100 Nobel Prize-winning scientists recalled ago. a few years. It is a case of raising the precautionary principle to the nth power that generates more harm than good.

In fact, the consequences have been disastrous: the blocking of the cultivation of any new transgenic variety in the EU and, now, the blocking of the cultivation of any new variety obtained by gene editing.

After the publication of that ruling, thousands of scientists, scientific societies, research centers, companies in the sector and institutions raised their voices against it, requesting a review of it (something impossible, court rulings cannot be appealed) or , at least, an intervention from the European Commission to change the directives and adapt them to the new gene editing technologies.

CRAG, Author provided

Unsuccessful block attempt

But back to the Reuters news headline. What was he referring to then? To a group of French NGOs that, after the judgment of July 2018, returned to the charge and asked the European high court once again to include the classic mutagenesis techniques (random, by radiation or chemical mutagens) in vitro (in cells, in tissues ) in the regulation as a GMO.

Fortunately, the new attempt to block varieties obtained by radiation or chemical mutagenesis has failed. The high court of the EU has responded that these mutagenesis techniques continue to be excluded from the regulation as GMOs by Directive 2001/18, confirming what the EFSA (European Food Safety Agency) itself had already established a couple of years ago.

Therefore, nothing is said in this new ruling on gene editing. They only refer to random mutation (the one obtained by radiation or chemical mutagens). Gene editing techniques are still considered GMOs and continue to require, in an incomprehensible way, regulation by directive 2001/18, published more than 12 years before the use of CRISPR gene editing techniques in plants was described.

The original version of this article was published in GenÉtica, the author’s blog in Naukas.