Brain’s ‘Internal Model of the World’ Isn’t Static, New Research Reveals

Table of Contents

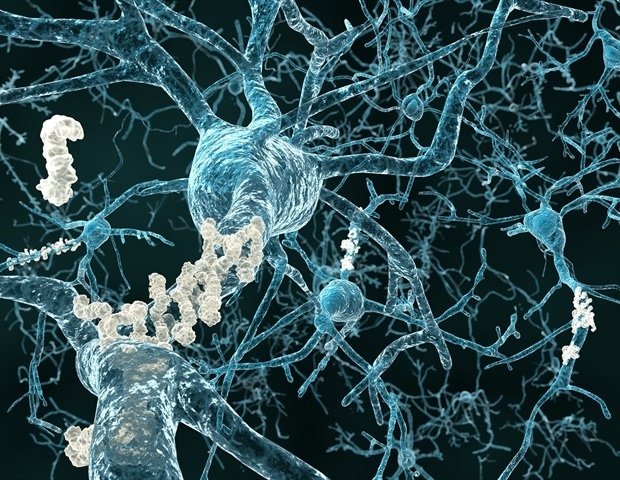

A groundbreaking study published in Nature demonstrates that the hippocampus, the brain region crucial for memory, actively reorganizes memories to predict future events – a process previously unobserved.

A team of researchers from the Brandon Lab at McGill University, collaborating with Harvard University, has uncovered a dynamic learning process that challenges conventional understanding of how the brain functions. The findings offer potential new avenues for understanding and addressing cognitive decline in conditions like Alzheimer’s disease.

The Hippocampus: More Than Just a Memory Store

For decades, the hippocampus has been understood as the brain’s central repository for memories, building cognitive maps of space and experience. However, scientists previously assumed changes in these maps occurred randomly over time. This new research reveals a structured, predictive element to this process.

“The hippocampus is often described as the brain’s internal model of the world,” explained a senior author of the study. “What we are seeing is that this model is not static; it is updated day by day as the brain learns from prediction errors. As outcomes become expected, hippocampal neurons start to respond earlier as they learn what will happen next.”

Tracking Neural Activity with Innovative Imaging

The research team employed cutting-edge imaging techniques – among the first in Canada to do so – that allow them to observe active neurons as they “glow.” This allowed for tracking brain activity in mice over several weeks, revealing subtle changes that would have been impossible to detect using traditional methods like electrodes, which are limited to short-term observation.

“What we found was surprising,” stated a researcher involved in the study. “Neural activity that initially peaked at the reward gradually shifted to earlier moments, eventually appearing before mice reached the reward.” This suggests the brain isn’t simply reacting to events, but actively anticipating them.

From Pavlov to Predictive Coding

The study builds upon earlier work demonstrating how simpler forms of learning – like the classic Pavlovian conditioning experiments with dogs – occur in more primitive brain circuits. However, the new findings suggest the hippocampus supports a more complex form of predictive learning, integrating memory and context to anticipate outcomes.

.

Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease Research

The ability to predict future outcomes is significantly impaired in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, who struggle with both recalling the past and making informed decisions. By demonstrating the hippocampus’s role in transforming memories into predictions, this research provides a new framework for understanding the cognitive deficits associated with the disease.

The study opens the door to investigating how this predictive signaling pathway breaks down in Alzheimer’s and exploring potential strategies for restoring it. This could lead to new therapeutic interventions aimed at preserving cognitive function and improving the quality of life for those affected by this devastating illness.

Source: Yaghoubi, M., et al. (2026). Predictive coding of reward in the hippocampus. Nature. doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09958-0. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09958-0