Saint Paraskevi is one of the most popular Saints of the Christian faith and particularly beloved by the faithful. This is evidenced by the multitude of churches dedicated to her name throughout the Greek territory and in other Christian countries. Smaller or larger churches, metropolitan or chapels, as well as monasteries throughout Greece, are dedicated to her name. Their large number demonstrates the significance of her sanctity for believers and her important place in the calendar of the Orthodox Church as well as in Greek society, much more so in the past than to a lesser degree today.

Every year, on July 26th, her memory is celebrated with particular splendor. This day is a significant occasion, especially for the Greek provinces and local communities where customs and traditions continue to survive to a considerable extent.

Venerable Martyr, Great Martyr, Virgin Martyr, Miracle-worker!

But who was Saint Paraskevi, who is called Venerable Martyr, Great Martyr, Virgin Martyr? Where did she get her name and why is she depicted in most of her iconography holding a Cross in her right hand and a tray with a pair of eyes in her left?

Answers to these questions are provided by her brief life and martyrdom, as described in her synaxarion.

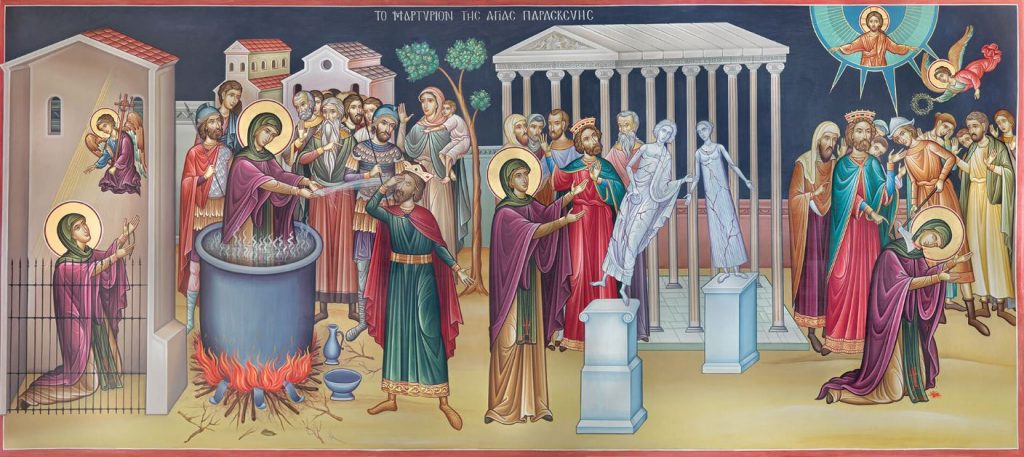

Her Martyrdom

Saint Paraskevi was born in 140 A.D. in Rome and died very young, at just 40 years of age, around 180 A.D., after a long martyrdom and ultimately beheading.

Her parents, Agathonikos and Politeia, were Christians with strong faith and had Paraskevi at an older age, after much prayer. Their daughter eventually came, albeit late, and they, as they had promised in their prayers, raised her according to the principles of the Christian faith.

How She Got Her Name

She was born on a Friday, and thus she was given the name Paraskevi. However, this was not simply a calendar choice by her parents, without theological substance or symbolism. If the daughter of the devout Christians Agathonikos and Politeia had been born on a Monday, they would not have called her Monday.

According to theologian Lampros Skontzos, “They named her Paraskevi because she was born on Friday, a day on which we prepare to celebrate the weekly feast of our Lord’s Resurrection, on Sunday.”

Proclaiming the Word of God

Saint Paraskevi was only 20 years old when her parents died. The time of her death was the starting point for her missionary work. She distributed the wealth she inherited from her parents to the poor and began to proclaim the Christian word in Rome and its surrounding areas.

However, this did not sit well with the pagan emperor Antoninus (138 – 160 A.D.). He ordered her arrest. She was captured, and he offered her riches and other goods if only she would renounce her Christian faith and embrace paganism.

The First Martyrdom

Icon of Saint Paraskevi. Vlassis Tzotsonis

Saint Paraskevi remained steadfast in her faith, resulting in her enduring a series of tortures until they finally broke her:

Initially, she was subjected to the torture of a heated helmet. Saint Paraskevi managed to endure it.

Then Antoninus ordered that the tortures against her be intensified. She was placed in a cauldron with boiling oil and pitch. She continued to endure, and he could not believe what he saw. So he approached to verify that Saint Paraskevi was in boiling oil and pitch, and from the hot vapors, he was blinded and begged for his sight.

The First Miracle

At that moment, she granted Antoninus his sight. As a result, the emperor believed in Christ and ceased the persecutions against Christians. This miracle established Saint Paraskevi as the protector of sight and eyes and the patron of opticians.

This is why she is depicted holding a tray with a pair of eyes and why in all her icons there are gold and silver offerings of a pair of eyes, seeking her protection.

After the miracle with Antoninus, Saint Paraskevi was set free and continued to preach the Gospel in many places, including Greece.

Archimandrite Silas Koukiaris, in his doctoral thesis “The life of Saint Paraskevi of Rome and of Iconium in Christian Art” (1994), states that Saint Paraskevi “with the power of divine word and the radiance of her sanctity attracted many pagans to the Christian faith.” Her miracles soon became known throughout the Roman Empire.

The Second Cycle of Her Martyrdom

After the death of Antoninus, Marcus Aurelius (161-180 A.D.) ascended to the imperial throne, who restored persecutions against Christians. Among the first Christians he arrested was Paraskevi. He ordered two governors, Asclepius and Tarasius, to torture her brutally. They subjected her to horrific tortures, which she endured, and finally, they beheaded her.

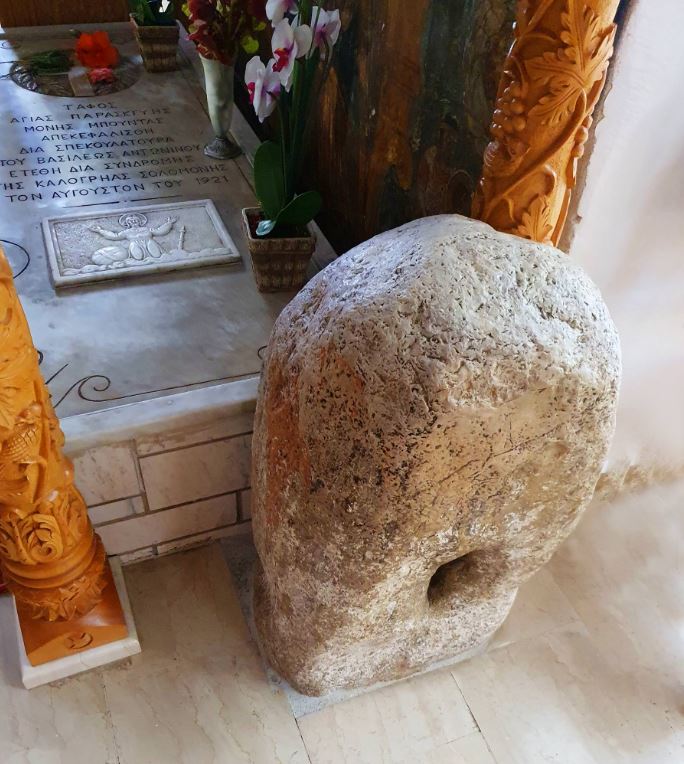

The Place of Her Final Martyrdom

While the manner of Saint Paraskevi’s martyrdom is preserved, there are various accounts regarding the place of her martyrdom. The recently ordained Elia Makos states that Saint Paraskevi ultimately suffered martyrdom in Greece and not in Rome, and this view is reinforced by the fact that it is not mentioned in the Roman martyrology.

The exact location of her beheading is a point for investigation, as she lived in the early Christian years, and her synaxarion does not provide detailed information.

Later researchers mention the Tempi of Larissa, where her temple exists, while others cite Thessaloniki. According to tradition, she likely suffered martyrdom in what was then Thesprotia, specifically in the area where the Monastery of Pounta is located today, near Kanali of Preveza, next to the mythical Acherousia Lake.

There also remains her tomb, in which her headless body is said to be buried.

On her tomb, a trichoric temple was erected in her honor, in which, according to tradition, her head was placed.

Next to the tomb, there remains the stone where she leaned and prayed while her executioner beheaded her.

Nevertheless, a part of her skull is hosted in the Petraki Monastery of Athens.

Spyros Mouselimis recounts of the moment of beheading: “During the time of the persecution, tradition says that they took the saint, tossing her here and there among the Roman soldiers, until they reached the edge of Acherusia Lake. As the soldiers approached and prepared to slaughter her, she grabbed onto a column that happened to be in front of her. The stone softened and turned into a green cheese out of anger. The holes of her sleeves and the fingers of her hands entered into the stone, where the marks can still be seen today. The body fell into a crack in the ground that occurred at the root of the stone, and the head was thrown to Rome to her parents, after stopping for a while at Splatsa, at the place where the church was later built for Saint Helena. The blood dripped onto the street from her head, frozen on land and in the sea, and her parents collected some of the blood and came to the place where she was killed. The Christians buried the body. The head that returned later remained unburied, and when they built the church, they placed it in the wall, which is visible today because it is from the outside.”

The Miracles of Saint Paraskevi

The miracles attributed to Saint Paraskevi after her martyrdom are countless. “Sick people who prayed with faith at her tomb were healed of incurable diseases, the possessed were freed from the bonds of evil, and barren women bore the long-desired child. Her reputation as the protector of eyes began from miraculous healings of the blind and those suffering from eye diseases.”

The grace of Saint Paraskevi was not limited only to the place of her burial. Throughout the Christian realm, where her memory was honored, miracles occurred and prayers were fulfilled. Churches and monasteries dedicated to Saint Paraskevi sprung up in every corner of the Byzantine Empire, testifying to the impact of her sanctity on the hearts of believers.

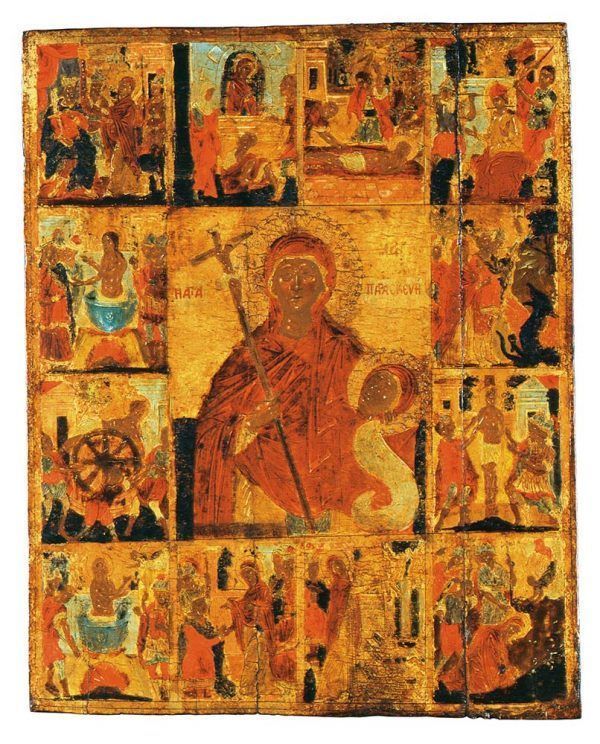

Significant is the presence of Saint Paraskevi in iconography. One way of her iconography is depicted holding the cross in her right hand and a tray with a pair of eyes in her left. A second way is instead of the tray with the pair of eyes, she holds her own head, as many of the Saints who have been beheaded. Finally, particularly interesting are the images, few in number, that refer to her life and the stages of her martyrdom.

Saint Paraskevi and scenes from her life

41.7 x 33 x 1.3 cm

2nd quarter of the 16th century

Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation

Velimezi Collection, donation of the Margaritis and Makris families

NUMBER OF DONATION 11

“In the center of the image, Saint Paraskevi is represented from the waist up, frontal. She holds in her right hand a cross with a long handle, with the Crucified, while in her left she holds her severed head, and an open scroll with an inscription that has been destroyed (it was replaced in a later re-painting with the inscription HOLY, HOLY, LORD SABAOTH). The two heads of the saint bear a halo with dotted decoration from a simple plant motif. Surrounding the central figure are twelve scenes narrating the martyrdoms and miracles of Saint Paraskevi according to her Life.

In the lower left corner of the central division, there is a false signature in black capital letters: HAND OF IOANNIS MOKKOS. To the right and left of the saint’s head in red letters: SAINT PARASKEVI. In the lower right corner of the last scene, of the beheading, the inscription can be seen: PRAY FOR THE SERVANT OF GOD […]. The earlier restoration has caused damage to the painting surface and to the gold background of the image, which had been filled in with repaintings that were removed during the recent restoration. Because of this damage, the preliminary incised design used by the painter is clearly visible, especially in the scenes surrounding the saint.

The characteristics of the saint’s face, as well as her clothing, with the dark-colored scarf covering her head, do not differ from known representations encountered in a large number of images from the 14th century onwards, such as in images from Veria, the Benaki Museum, London, and Patmos, where she is depicted holding a cross.

The presence of the Crucified above the cross that Saint Paraskevi holds in her image from the Velimezi collection relates to the Passion of Christ, which is symbolically referenced in earlier representations of the saint, where she holds an image of Extreme Humility. In images from the 14th century onwards in Cyprus, we often encounter this type, where sometimes the saint is identified with Good Friday. A representation of Saint Paraskevi holding the Crucified, as in our image, is also found in an image from the 12th century in Ravenna, where she is depicted full-length holding a palm branch in her left hand, without the other iconographic traits of our image type.

The Crucified remains a stable feature in the iconography of other saints, such as Saint Catherine in a series of images from the end of the 16th century, in the famous examples of Ieremias Palladas and Emmanouil Lambardos. Additionally, the Crucified is also held by Saint Barbara in a 17th-century image in Cephalonia. Finally, in a series of images from the 17th century onwards, the Virgin Mary in the iconographic type of the Sorrowful Virgin also holds the Crucified.

The representation of the saint holding her head can be classified among the representations of head-bearing saints, such as Saint George, who is always depicted in a lateral stance in well-known examples up until today. In a similar posture, at three-quarters view, the head-bearing Saint Catherine is depicted in a well-known Cretan image from the 17th century in the Latsis collection, where she is surrounded by six scenes from her life. In an image of Saint Sophia in Riana degli Albanesi from the end of the 16th century, the saint is depicted in a similar type to that of Saint Paraskevi.

She is depicted frontally holding in her left hand a tray with the severed heads of her three daughters, and in her right a cross with a long handle. A model for these representations can be considered the depiction of Saint John the Baptist holding his head, already from the Palaiologos period, in a frontal stance, as in the oldest known example in Arilje from 1296. The frontal stance of Saint Paraskevi in our image likely has as its model a corresponding representation of the Forerunner. This hypothesis is confirmed by the even greater resemblance that Saint Paraskevi in our image bears to the representation of Saint John the Baptist in an image from Patmos at the end of the 16th century, where the frontal stance of the two saints is shared, as is the way they hold their head along with an unrolled scroll in the same hand.

Saint Paraskevi holding her head is a theme known in frescoes as well as in the painting of icons. In a frontal stance, holding with her raised right hand a tray with her severed head, she is depicted in a fresco in the church of Saint Nicholas in Kastoria, as well as in the church of Annunciation, dated 1690, in the Nymphs of Corfu.