The boy dated a cop, looked down on the cops, got close to the cops. Although he was only thirteen, his posture made him look like a policeman – but in plainclothes. A book by the writer and translator Jan Zábrana, which was published on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of his death, also contains the subject for a never-written short story.

Another volume of Zábran’s works, this time more of notes on the work, was published by the Torst publishing house under the title Excerpce. It includes rambling pub gaffes such as “In the first year, his mother could no longer wrap him, as he was making puppets for him”, personal tasks such as “Translate the second sonnet of Feldek”, as well as entire poems, reflections or records about himself and the times.

They are all seeds from which the work was yet to be born. But Jan Zábrana, who lived from 1931 to 1984, did not have enough time for that.

The wider public has known him for a long time as an author of detective stories, an editor, and especially a translator under dozens of remarkable titles. He translated texts by Isaak Babel, Sergey Yesenin and Boris Pasternak from Russian into Czech, and from English by Allen Ginsberg, Sylvia Plath and Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

It wasn’t until the publication of Zábran’s diaries under the title Whole Life in the early 1990s that catapulted him among the most important writers of the second half of the last century. The testimony of a man whose mother and father were condemned in political trials by the Communists after the coup in 1948 and who was allowed to publish mostly only translations, not his own work, under their rule sold over ten thousand copies and won the People’s Newspaper Book of the Year award.

Bitter and precisely targeted notes in the eyes of many readers rehabilitated the genre, which is now called English non-fiction, and opened the way for other memoir literature. In the diaries, Zábrana was able to uncover the similarly buried layers that we find in the best novels.

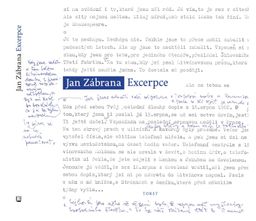

Jan Zábrana always carried a notepad with him. | Photo: Torst publishing house

The now published Excerpts, on the other hand, offer rather a unique insight into his literary workshop. Zábrana carried notebooks with him all his life, in which he recorded daily situations, couplets, rhymes that occurred to him, personal attitudes, lines that he uttered or, on the contrary, kept silent when meeting someone for various reasons.

He later went through some of these notes from the 1950s to the 1970s thoroughly and typed those he considered to be relevant. Sometimes he did not even fully decipher the old manuscript, but still included passages in the selection.

Hence the name Excerpce, which means taking extracts from another work. In this case, only Zábrana applied the method to himself. “It was his attempt to organize his records and himself at the beginning of normalization,” explains the annotation.

The typewritten notes in A4 format were only recently discovered in the estate by editor Jan Šulc, who worked on many of Zábran’s titles, and prepared their reduced facsimiles for publication.

Above them, the reader can remember how Zábrana compiled a small collection in 1970 called How a Poem Is Made. In it, he selected essays in which his favorite authors reflect on the creation of a poetic composition, and supplemented it with samples of their work. The result was a kind of poetry book or cookbook, a remarkable volume with lasting validity.

Now something similar happened to Zábran. The snippets, observations and notes collected in Excerpts could be characterized by the phrase How a poem is made. Or better yet: How to journal.

They show that Zábrana constantly worked on his texts. He repeatedly edited and chiseled his own translations, poems and prose. He also read already published books with a pencil in hand and thought about how to refine them for the next edition. From his diaries and now again from the Excerpts, it is clear how brilliantly he was able to formulate even in the first version.

Excerpts are like death – they take everything. High and low, essential and shallow, all that Zábrana could add up to make a tally of in the future. However, this did not happen, the man of letters succumbed to cancer at the age of only 53, and dust fell on the transcripts for years.

Torst published them in a slightly different format than previous Zábran writings. To keep the reduced facsimile legible, the Excerpts were enlarged.

It is not a volume that would bring Jan Zábrana closer to an uninitiated reader. However, those who at least have a basic understanding of it have a unique opportunity to be present in the creation of a work. It is essentially fragmentary reading, yet dense, complete in its own way. However, Zábrana was fighting for fullness. All life.

Jan Zábrana: Excerpce

Torst Publishing House 2024, 92 pages, 248 crowns