Contrary to the prevailing assumption until now, a team of researchers from France and Chad discovered that walking on two feet does not characterize only Homo sapiens and may have evolved several times. several times and gradually

authors: Jean-Renault Bousserieresearch director at CNRS, paleontologist, University of Poitiers, Endosa Lyciusthe Franco-Chadian Paleoanthropological Mission, University of N’Djamena (Chad), Clarisse Nkwlanang DjatunakuResearch Professor in Paleontology, University of N’Djamena (Chad), Frank GuyPaleoanthropology, University of Poitiers, Guillaume DaubertLecturer in Paleoanthropology, University of Poitiers, Lauren PalacePaleontologist, Kyoto University, Makiya Hasan TaisoPaleontologist, University of N’Djamena (Chad), Patrick VigneaultProfessor of Paleontology, University of Poitiers

Today’s species research has provided a clear verdict on humanity’s place in the living world: right alongside chimpanzees and bonobos. However, it doesn’t tell us much about our earliest human representatives, their biology or geographic distribution—in short, how we became human. To do this, we have to rely mostly on the morphology of frustratingly rare fossils, since paleogenetic information is preserved only from recent periods – and even then, in fairly cool climates.

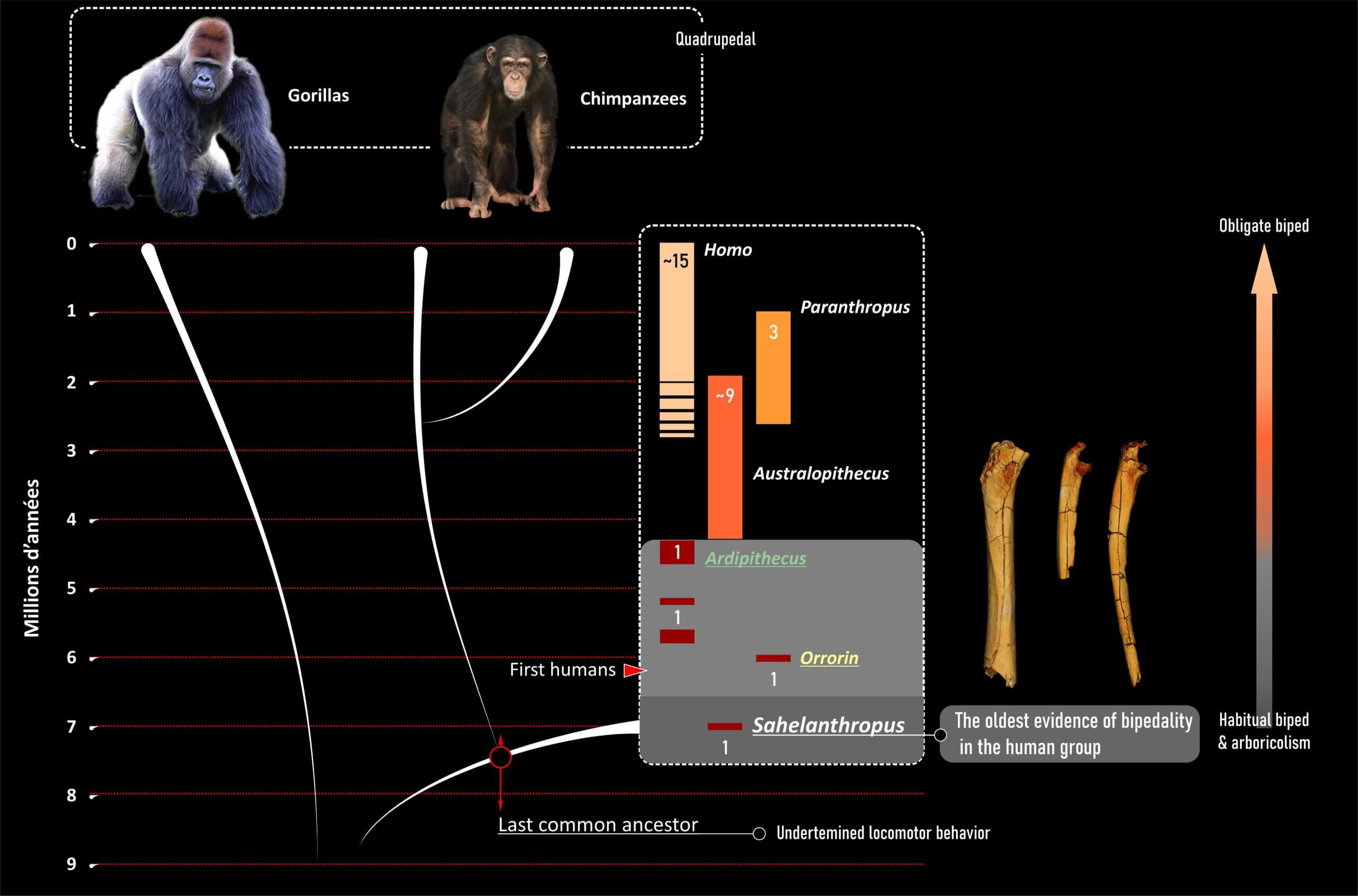

Since the 1860s and identifying the very early era of Australopithecus – including the famous 3.18 million year old Lucy, discovered in 1974 in Ethiopia – the adoption of walking on two legs is considered a decisive step in human evolution. Indeed, it is an essential trait that marks the transition from ancient human species to more modern species long before the significant increase in our brain size.

There was much anticipation for our study, which was published on August 24 in the Journal The journal Natureon the skeleton of Sahelanthropus tchadensiswho is a candidate for the title of the oldest known representative of humanity.

If so, were our distant ancestors human or non-human? In reality, asking the question in these terms borders on circular reasoning. Given that we have yet to discover the last common ancestor we share with chimpanzees, we do not know the initial state of human locomotion—bipedal or otherwise.

Until now, the earliest data available to us were the limb bones of Ororin (6 Ma, Kenya) – Ardipithecus (5.8 Ma–4.2 Ma, Ethiopia), which exhibited a different type of bipedalism than later species. It turns out that bipedalism is not an immutable characteristic of humanity and has its own history within our history. The right question is therefore: were the first representatives of humanity bilateral, and if so, to what extent and how? This is the question our Franco-Chadian team sought to answer by investigating the much older remains (about 7 Ma) of Sahlanthropus.

existence of Sahlanthropus First inferred in 2002 from a deformed but well-preserved skull (known as a tomai) and several other craniodental specimens discovered by the French-Chadian Paleoanthropological Mission (founded by Michel Brunt) at Touros-Manala in the Jurab Desert in Chad, dating from at least three Details. The study is based primarily on the morphology of the teeth, face and braincase of this species compared to more recent human fossils.

The limb bones described in our article include a partial left femur (femur) and two left and right ulna bones (along with the radius, the ulna is one of the two bones in the forearm that form our elbow). These bones were found in the same locality and in the same year as the skull, but were identified later in 2004. It is likely that they belong to the same species as the skull, since only one large primate was identified out of almost 13,800 fossils representing about 100 different vertebrates in 400 localities in Taurus- Manala. However, it is not known if the femur, ulna and skull belong to the same person, as at least three different individuals were found at the site.

A number of factors slowed our research, which began in 2004. For example, we were required to prioritize field study of other postcranial remains while struggling to analyze fragmented material. We eventually relaunched the project in 2017 and finished it five years later.

Bones studied from every possible angle

Given the poor preservation of these long bones (the femur, for example, has lost both ends), short analyzes cannot provide reliable interpretations. That’s why we studied them from all angles, both in terms of their external morphology and their internal structures.

To reduce uncertainty, we used an extensive array of methods, including direct observations and biometric measurements, 3D image analysis, shape analysis (morphometrics), and biomechanical indicators. We compared the Chadian material to today’s fossil samples using a prism of 23 criteria. Individually, none of them can be used to suggest a categorical interpretation of the material – indeed, there are no “magic” properties in paleoanthropology, and all will be subject to debate in the scientific community.

At the same time, these features result in an interpretation of these fossils that is much stronger than any alternative hypothesis. This combination therefore indicates that Sahelanthropus moving on his two legs all the time. Both on the ground and on the trees. In the latter case, it is likely to have been accompanied by a quadrupedal gait accompanied by grasping branches, in contrast to the quadrupedal gait practiced by gorillas and chimpanzees, known as “walking on the knuckles”, in which the weight is supported by the back of the phalanges.

The results are consistent with observations made on Ororin Vardipithecus, and they have several consequences. First, they reinforce the idea of a very early form of bipedalism in human history coexisting with other modes of locomotion. Thus there was no “sudden” appearance of a characteristic unique to humanity from the very beginning, but a long and slow transition lasting millions of years.

The human species is but a fragment of biological diversity

This phase of human evolution has thus occurred in fairly common ways throughout the history of life and throughout the world, and it reminds us that our species is but a sliver of biological diversity. This fact alone should lead us to rethink our relationship to the living world and the parameters that govern the hospitality of our planet.

Second, the characteristics of Sahlanthropus, Ororin and Ardipithecus point That the ancestor we share with chimpanzees was neither chimpanzee-like nor the exclusive chimpanzee we became. Contrary to the hypothesis that chimpanzees and bonobos retained their primitive morphology, it is more likely that their particular combination of vertical climbing and “knuckle walking” evolved long after our split.

Finally, if Sahelanthropus tchadensis It is a witness to human diversity among other things, it is, to this day, the only bipedal species known from that time. Given the complete, weakly diversified hominoid fossil record of Africa and Eurasia in the late Miocene (10 million years ago), the acquisition of bipedal walking by the human branch in continental Africa remains the only well-documented hypothesis to date. At this point, bipedalism appears to be part of an opportunistic locomotion repertoire—flexible, able to exploit different environments—that fits well with the diverse paleoenvironment of Toros-Manala as reconstructed by our team’s geologists, paleobotanists, and paleontologists.

This article was co-authored by Abdelmanah Moussa (University of N’Djamena, Chad).

For an article in The Conversation