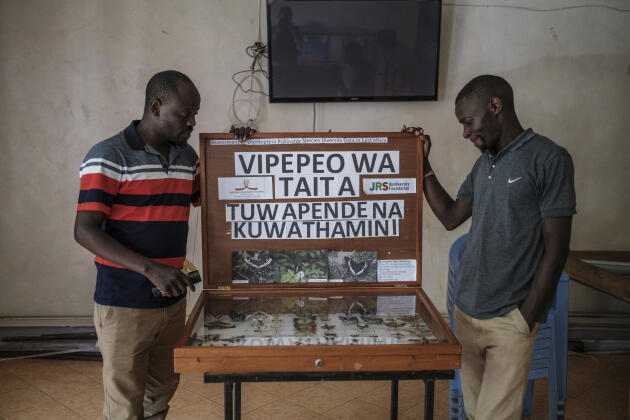

Failing to obtain the support of the Kenyan authorities, they themselves protect their forest. Nathaniel Mkombola and John Maganga have rolled up their sleeves to prevent the disappearance of the Ngangao Forest, in Wundanyi, in southwestern Kenya. This small jewel of biodiversity, nestled in the Taita mountain range, threatened to disappear under the pressure of neighboring villages, in constant search of firewood and new land to cultivate.

The two forties, co-founders of the organization Dawida Biodiversity Conservation Group, grew up on the edge of the woods. “I heard the streams flowing from the forest alongside my house when I was a child, remember John. Then growing up, nothing! » The awareness took place in 2011, when Dawida was created. Since then, they have been patrolling the forest, conducting awareness campaigns in the villages, listing bird species, replanting endemic trees in the Ngangao watershed.

Because if the government made the forest a public domain in the 1980s, it did not protect it from overexploitation. Witness the only ranger in charge of monitoring the 120 hectares of woods… In thirty years, the entire Taita mountain range has lost 50% of its forest cover. To reduce deforestation, Dawida members distribute stoves with low wood consumption.

Ngangao has sometimes come close to disaster. “We discovered earlier this year that there was only one Afrocarpus Usambarensis left in the forest”, says Nathaniel Mkombola. This endemic conifer is endangered in Kenya and Tanzania. Since then, they have replanted two thousand thanks to their nursery.

Ambitious goal

Officially, a permit is required to go into the forest and collect wood there, but in practice, the lonely ranger cannot control all the comings and goings. In 2015, Dawida therefore initiated a forest conservation recognition process with the Kenyan State, with a dual objective: to fully protect Ngangao while sharing part of the benefits of ecotourism with the surrounding villages. Seven years later, the project is at a standstill, the State does not respond.

The case of Ngangao encapsulates the contradictions facing Kenya today, as the country is set to commit to protecting 30% of its land areas by 2030, as part of the agreement on the menu of the United Nations Conference on Biodiversity (COP15), which begins its work on Wednesday, December 7 in Montreal.

The objective is ambitious: the country, renowned for its safaris, now only has 12.4% of protected land. However, Kenya had initially committed to preserving 17% of it by 2020, during the Aichi conference in 2010. If an agreement is reached in Montreal, Kenya will no longer have to protect 69,917 km2plus 174 795 km2 of its territory.

It is unclear how the country will move towards the 30% target. “The Kenyan authorities are not going to create new parks or nature reserves, informe Nancy Githaiga, directrice de l’African Wildlife Foundation, one of the African flagships for conservation on the continent. They plan to agree with local communities to protect public land. »

“Do no harm to indigenous peoples”

The idea would therefore be not to sanctuarize new spaces, such as parks or nature reserves (Kenya has fifty of them), because this would imply possible population displacements. For the future, the main axis of conservation is at the level of the creation of new conservanciesa hybrid mode of protection in which the land belongs either to private actors or to NGOs or local communities.

It is on this narrow crest line that the Kenyan State is committed, which promises both to extend the lands under protection and to include the indigenous communities, historical owners of these plots. “Obviously everyone says yes to the protection of the environment, but this must not harm the indigenous peoples”warns Ramson Karmushu, a researcher with the organization Impact Kenya. “It is high time to find conservation modalities that include indigenous populations, instead of expropriating them”, he continues.

Defenders of these local communities are particularly concerned about the precedent observed in Tanzania. A legal battle has started there after the Tanzanian authorities plan to expel 80,000 Maasai from their ancestral lands in the Ngorongoro conservation area, to promote tourist activities there.

“Africa must finance itself”

“We undeniably have a problem with biodiversity loss, but the model Kenya is pursuing could turn out to be the biggest land grab from indigenous peoples ever seen, alert Anuradha Mittal, director of the Oakland Institute. The risk of 30% is the accelerated exclusion of the natives “, she warns. According to the WWF, indigenous communities represent less than 5% of the population but protect 80% of the world’s biodiversity. To reassure them, Nairobi could proclaim the Natural Resources Bill, a law that would redistribute 12.8% of biodiversity benefits to local communities. But voted four years ago, the text is still waiting to be promulgated.

The other unknown concerns the financial resources to achieve this. Kenya is one of the countries that will demand the establishment of a global fund for the safeguarding of biodiversity, which could be between 10 and 100 billion dollars per year. According to the United Nations Environment Program, 536 billion dollars (510 billion euros) annually are needed to effectively combat the degradation of fauna and flora by 2050.

African conservationists, however, fear that donors will continue to dictate terms in Africa. “Previously, conservation was exclusively a colonial work, then almost entirely undertaken by Western foundations, assure Nancy Githaiga de l’African Wildlife Foundation. Now we have to think differently. Africa must finance itself, it is the only solution to have our own agenda, so that our voice is heard. »

Indeed, while Nairobi fully funds the rangers of the Kenyan Wildlife Service, the public entity for the protection of the parks, a large part of the funds intended for conservation come from abroad. The African Wildlife Foundation itself benefits from numerous sponsors from the West such as Royal Canin or the largest American environmental protection NGO, The Nature Conservancy.