On often presents Archimedes as the first great scientist to have used his scientific knowledge to build war machines. During the Siege of Syracuse in 212 BC, he is said to have constructed giant parabolic mirrors to ignite enemy sails by concentrating the Sun’s rays. While the anecdote is certainly not true, it illustrates one of the earliest uses of science in warfare.

However, Archimedes was also a “pure” mathematician to whom we owe treatises on geometry that have marked the history of science. When a Roman legionary came to disturb him while he was drawing a geometric figure in the sand, he replied: “Don’t Disturb My Circles”and the soldier killed him with a blow of his sword.

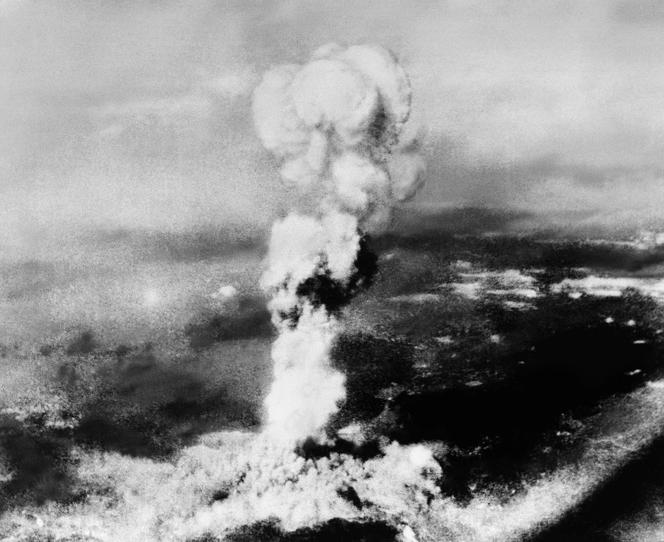

Much later, during the Second World War, the Manhattan Project in the United States brought together in the greatest secrecy a considerable number of engineers, physicists and mathematicians with the aim of building the first atomic bombs, far more powerful than the Archimedean mirrors. On August 6 and 9, 1945, the bombs killed more than 100,000 people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The whole world became fully aware of the determining role of the scientific community in the war.

At the end of the First World War, like the League of Nations, many scientific disciplines created international unions. The International Mathematical Union (IMU), for example, was founded in 1920 and organizes a very prestigious international congress every four years which takes stock of progress in mathematics: in a way, the Olympic Games of Mathematics.

No peaceful agreement

However, we should not believe in a peaceful understanding between all the mathematicians of the world, ignoring wars and political conflicts. For example, when the IMU was founded, German mathematicians were not invited, and to mark the victory, the opening ceremony took place in Strasbourg, recently again in France. The congresses were canceled during the Second World War and very disrupted during the Cold War.

In Cambridge (United States), in 1950, no Soviet delegate nor any from communist Eastern Europe took part, although several had been invited. The Soviet Academy of Sciences had claimed that Soviet mathematicians had too much work to travel. The United States had initially refused the entry visa for the Frenchman Laurent Schwartz, a communist, who came to collect his Fields medal. In 1966, Alexandre Grothendieck refused to go get his medal in Moscow. The congress which was to take place in Warsaw in 1982 was postponed and was held the following year. The history of this international mathematical union is indeed very chaotic.

You have 21.88% of this article left to read. The following is for subscribers only.