Scientists have detected lithium on Mercury, a discovery long sought but never confirmed. For decades, researchers suspected the elusive element might be present in the planet’s wispy exosphere, but attempts to find it proved fruitless until now. Instead of spotting lithium atoms directly, scientists used an ingenious method: they identified its distinct electromagnetic fingerprint. By analyzing magnetic waves, they managed to capture the unmistakable signature of lithium ions being swept along by the solar wind.

Electromagnetic Waves Reveal Mercury’s Hidden Lithium

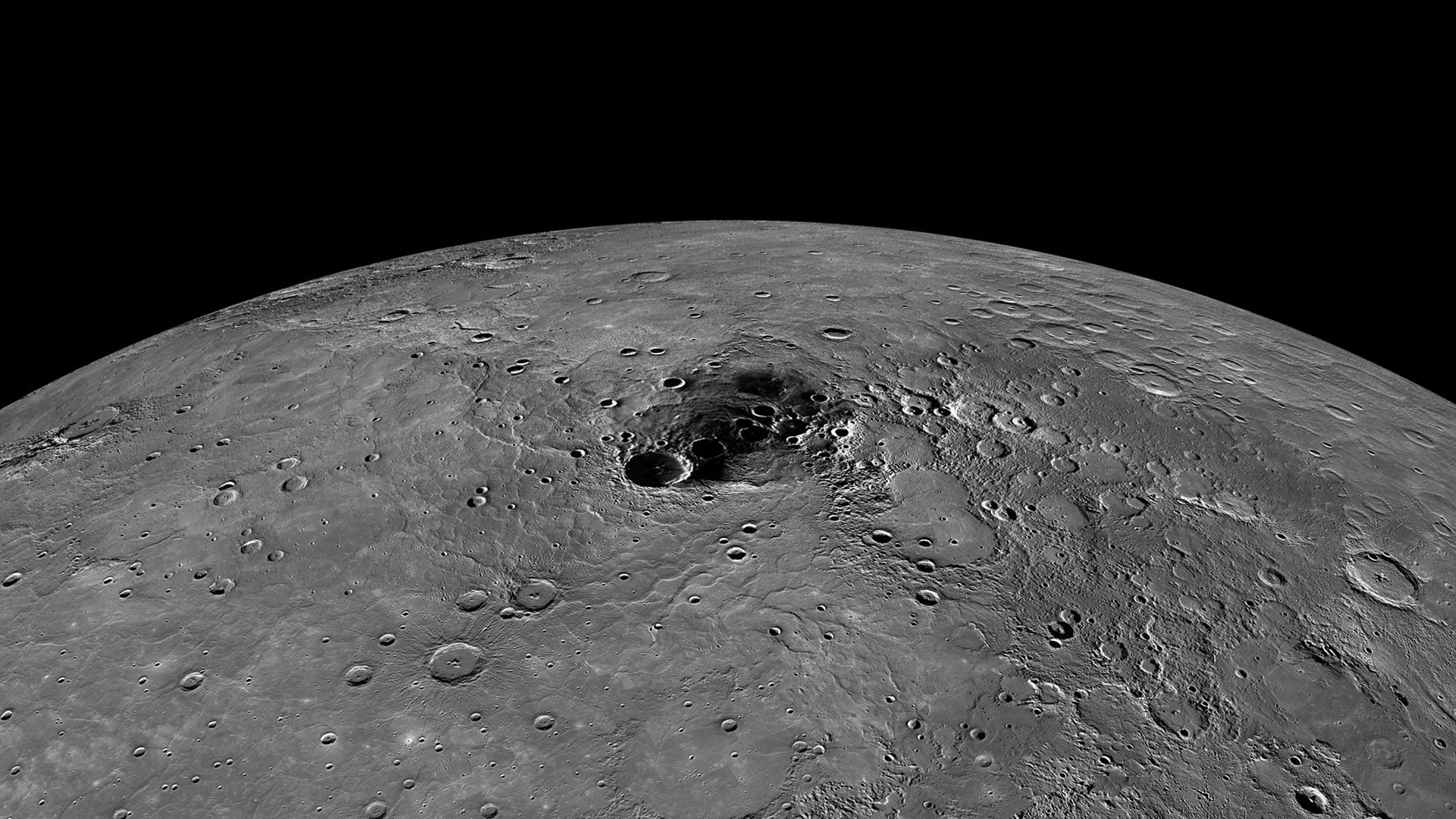

This groundbreaking finding marks the first confirmed identification of lithium on Mercury, offering crucial evidence of the planet’s ongoing chemical activity and its dynamic surface shaped by constant meteoroid impacts.

“During our survey, we identified signatures of pick-up ion cyclotron waves that could be attributed to freshly ionized lithium,” said Daniel Schmid, lead author of the study and a researcher at the Austrian Academy of Sciences.

Mercury’s exosphere is incredibly thin and sparse, unlike Earth’s dense atmosphere. Atoms here are so spread out they rarely interact. Previous missions, including Mariner 10 and MESSENGER, had already confirmed the presence of elements like hydrogen, sodium, potassium, and iron. Given that potassium and sodium are alkali metals, similar to lithium, scientists long theorized lithium’s presence.

Did you know? Lithium is notoriously difficult to detect in low concentrations, making direct observation on Mercury a significant challenge for traditional instruments.

The hurdle was lithium’s presumed extremely low concentration, making it nearly impossible to detect with standard particle detectors or telescopes. Schmid and his team pivoted their strategy, shifting focus from the atoms themselves to how lithium ions interact with the solar wind.

Meteoroid Impacts Unleash Lithium into Mercury’s Exosphere

When meteoroids collide with Mercury’s surface, they vaporize crustal material, releasing neutral lithium atoms. These atoms are then rapidly stripped of electrons by the sun’s intense ultraviolet radiation, transforming them into positively charged lithium ions. This is where the detection method shines: as the solar wind captures these fresh lithium ions, it generates a specific electromagnetic disturbance known as ion cyclotron waves (ICWs).

These waves possess a unique frequency directly tied to the mass and charge of the involved ion—essentially acting like a specific radio frequency for lithium. By meticulously sifting through four years of magnetic field data from the MESSENGER spacecraft, the researchers identified 12 distinct events exhibiting these “lithium-tuned” waves.

Each event, lasting only tens of minutes, provided brief glimpses into the process of lithium being ejected into the exosphere. The team confirmed these weren’t passive occurrences, ruling out gradual processes like solar heating and pinpointing sudden, energetic events: meteoroid impacts.

- Lithium has been confirmed in Mercury’s exosphere for the first time.

- The discovery was made by detecting electromagnetic “fingerprints” of lithium ions, not the atoms directly.

- Meteoroid impacts are believed to vaporize surface material, releasing lithium atoms that become ionized and interact with the solar wind.

- Data from the MESSENGER spacecraft was crucial in identifying ion cyclotron waves associated with lithium.

- This detection method could be applied to other celestial bodies with thin or no atmospheres.

Meteoroids ranging from 13 to 21 centimeters in radius and weighing 28 to 120 kilograms, striking Mercury at speeds up to 110 kilometers per second, create powerful mini-explosions. These impacts can heat surface material to temperatures between 2,500–5,000 Kelvin, launching lithium atoms into space. Astonishingly, a single impact can vaporize an amount of material 150 times the meteoroid’s own mass.

“The detection of lithium and its association with impact events strongly supports the hypothesis. It demonstrates that meteoroids not only deliver new material but also vaporize existing surface deposits, releasing volatiles into the exosphere and sustaining a dynamic cycle of supply,” Schmid explained.

A New Method to Uncover Planetary Secrets

Contrary to prior assumptions that Mercury’s proximity to the sun would have long ago stripped away volatile elements like lithium, MESSENGER data had already indicated the planet’s capacity to retain such substances. This new study reinforces a compelling hypothesis: meteoroid bombardments continuously enrich Mercury’s surface, acting as a delivery system for elements and releasing them into space through high-energy impacts.

The implications extend far beyond Mercury. The wave-detection technique offers a powerful new tool for studying other airless or thin-atmosphere bodies, including the Moon, Mars, and even asteroids, where direct detection of rare elements is exceedingly difficult.

“This has important implications for understanding surface chemistry and long-term space weathering across the inner solar system,” Schmid added. His team anticipates that future missions equipped with more sensitive instruments will further validate and expand upon these exciting findings.

The study is published in the journal Nature Communications.