Artemis Missions Poised to Unlock Lunar Secrets Hidden Within Ancient Impact Basin

A new study published in teh journal Nature suggests that NASA’s upcoming Artemis missions will land in a prime location to unravel the mysteries of the moon’s formation and evolution, specifically within the vast South Pole-Aitken basin. The research offers a compelling explanation for the dramatic differences between the moon’s near and far sides,and sheds light on the distribution of key elements crucial to understanding our celestial neighbor.

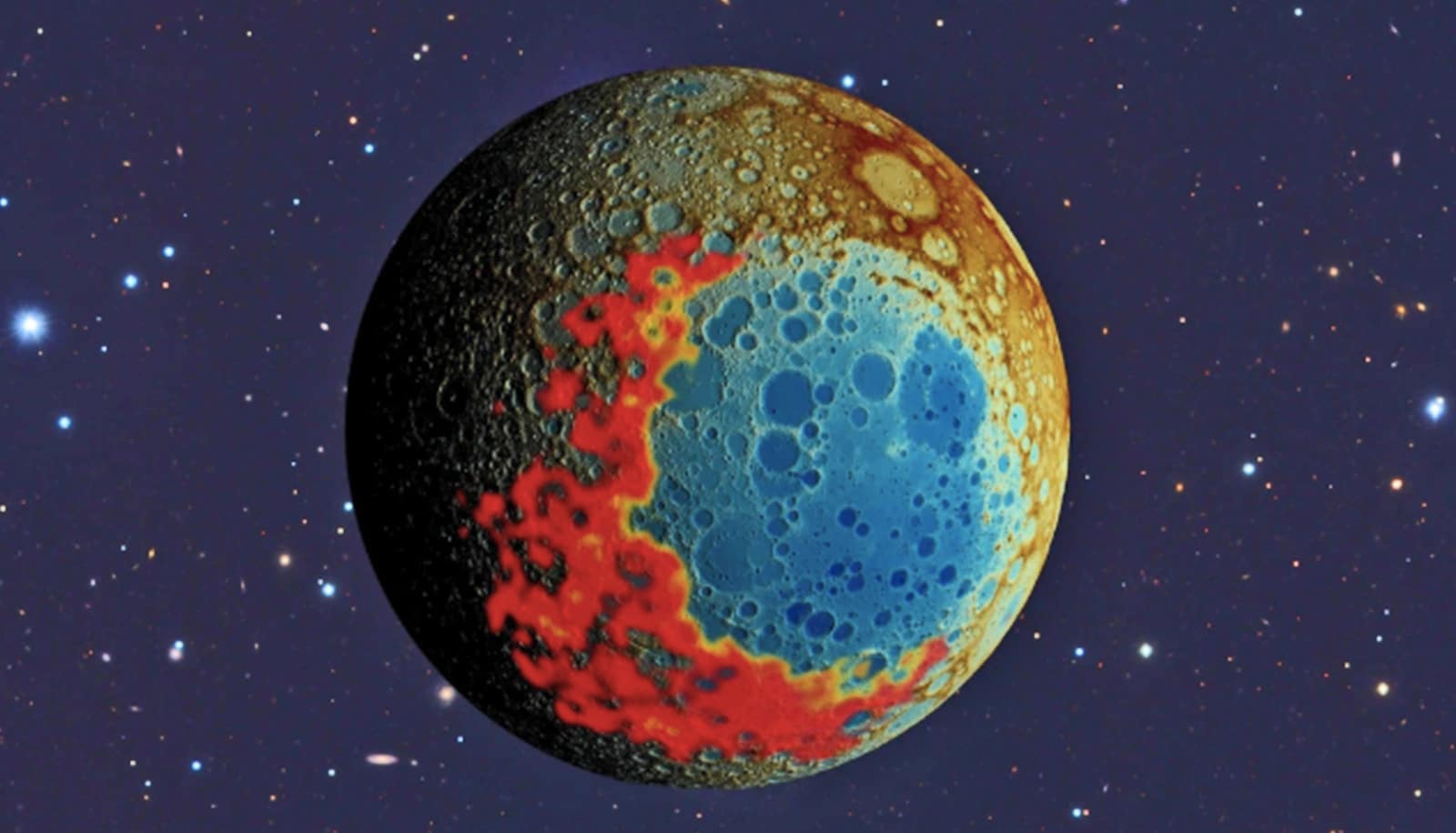

The moon’s history is etched in its landscape, notably within the South Pole-Aitken (SPA) basin, the largest known impact crater in the solar system.For years, scientists believed the impact that created SPA originated from the north, but new evidence suggests it came from the south as previously believed.

“By comparing the shape of SPA to other giant impact basins, we found they narrow in the down-range direction, resembling a teardrop or avocado,” explained a senior researcher involved in the study. this finding is critical as the “down-range” end of the basin-where material ejected from deep within the moon’s interior would have accumulated-is precisely where the Artemis missions are slated to land.

This strategic landing site will provide astronauts with unprecedented access to material excavated by the impact, offering a unique window into the moon’s deep interior. Analyses of the basin’s topography, crustal thickness, and surface composition further support the northern impact theory. The research also provides new insights into the moon’s internal structure and its evolution over billions of years.

Early in its history, the moon is believed to have been covered by a global magma ocean. As this ocean cooled, heavier minerals sank to form the lunar mantle, while lighter minerals rose to create the crust. However, certain elements-potassium, rare earth elements, and phosphorus-collectively known as KREEP-didn’t fit neatly into either layer. Instead, they remained concentrated in the remaining liquid magma.

“Think of it like leaving a can of soda in the freezer,” a planetary scientist explained. “As the water freezes, the high fructose corn syrup resists and concentrates in the last bits of liquid. Something similar happened on the moon with KREEP.”

This KREEP-rich material ultimately became concentrated on the moon’s near side, fueling intense volcanism that created the dark volcanic plains visible from Earth-the “face” of the moon. However, the reason for this uneven distribution remained a long-standing puzzle.

the moon’s far side boasts a considerably thicker crust than its near side,a key asymmetry that has baffled scientists for decades. Andrews-Hanna and his team propose a compelling solution: as the far-side crust thickened, the remaining magma ocean was squeezed out towards the sides, ultimately accumulating on the near side.

Recent analysis of the SPA impact crater provides strong evidence supporting this theory. the ejecta blanket on the western side of the basin is rich in radioactive thorium, while the eastern flank is not. This suggests the impact exposed a boundary between the crust overlying the KREEP-enriched magma ocean and the “regular” crust.

“Our study demonstrates that the distribution and composition of these materials align with predictions based on models of the magma ocean’s evolution,” Andrews-Hanna stated. “The last remnants of the lunar magma ocean ended up on the near side, where we observe the highest concentrations of radioactive elements.”

While remote sensing data has provided valuable insights, researchers eagerly anticipate the return of lunar samples from the Artemis missions. These samples will undergo detailed analysis in state-of-the-art facilities,including those at the University of Arizona,to further refine our understanding of the moon’s early history. .

“With Artemis, we’ll have samples to study here on Earth, and we will know exactly what they are,” Andrews-Hanna concluded. “Our study shows that these samples may reveal even more about the early evolution of the moon than had been thoght.”

Source: University of Arizona