Sept. 11, 2025, 03:23:00 AM EDT

The connection between your gums and your brain might be stronger than you think. New research suggests that chronic gum disease, known as periodontitis, could significantly increase the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. This link appears to stem from systemic inflammation and the infiltration of oral pathogens into the brain, potentially accelerating neurodegenerative processes.

- Chronic periodontitis may elevate Alzheimer’s disease risk.

- Oral bacteria and inflammation can spread to the brain.

- Lifelong oral hygiene is crucial for brain health.

- Early detection and treatment of gum disease are vital.

What is the link between gum disease and Alzheimer’s?

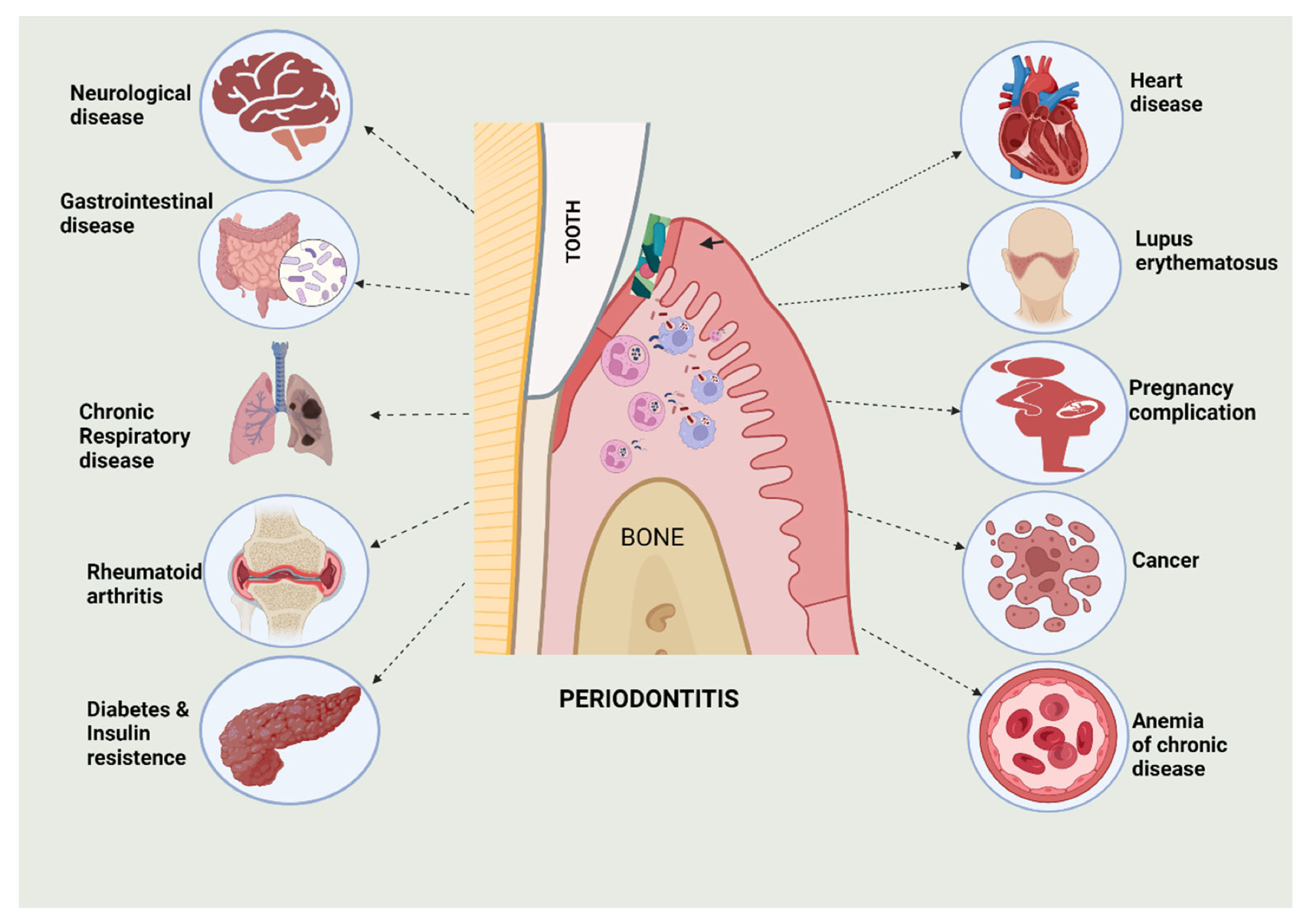

Periodontitis, a common inflammatory condition affecting the gums and bone supporting teeth, may increase Alzheimer’s risk by fostering widespread inflammation and allowing oral bacteria to reach the brain.

The Mouth-Brain Connection: Inflammation’s Role

Table of Contents

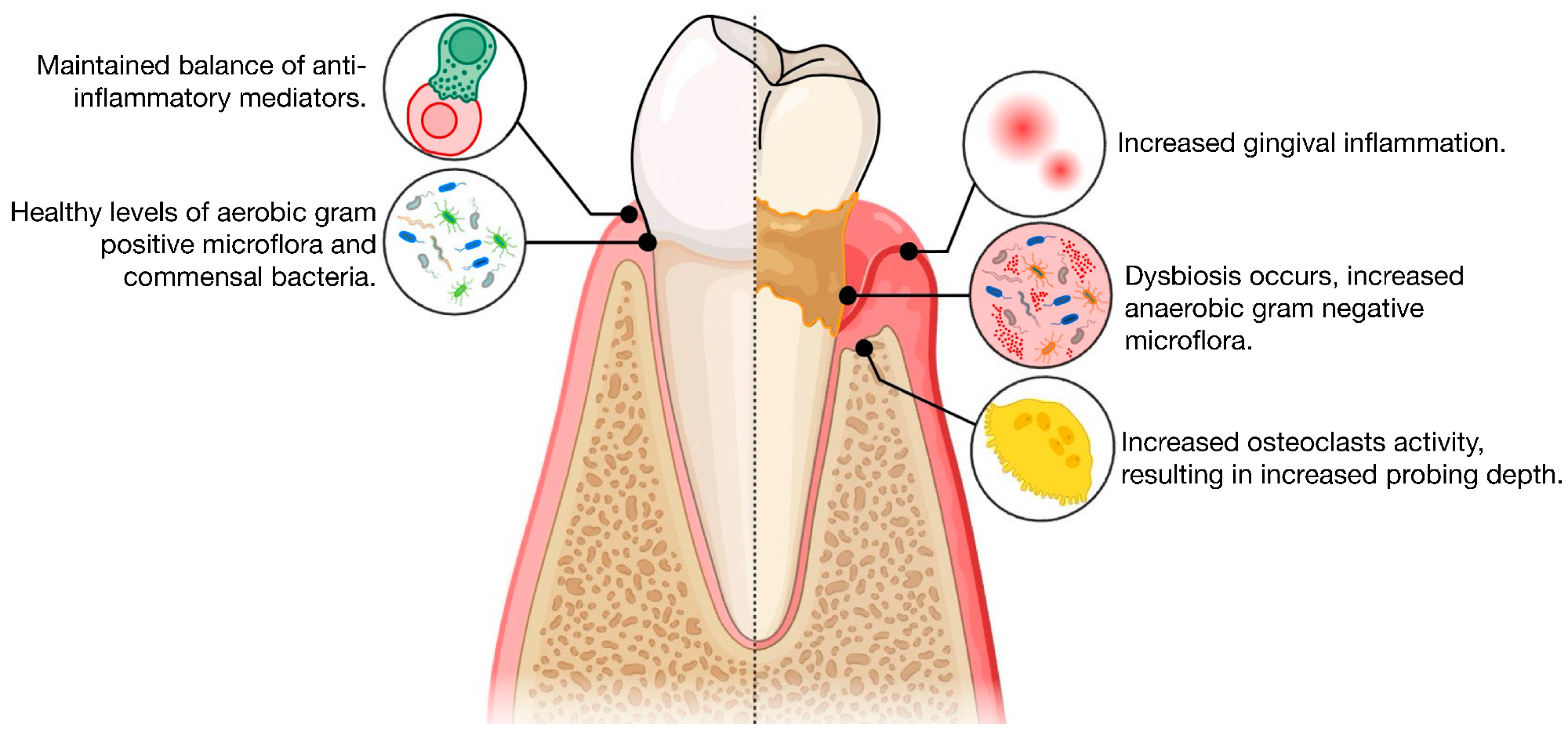

Periodontitis starts with a buildup of bacteria, forming a dysbiotic plaque. This persistent bacterial presence triggers chronic inflammation. Deeper gum pockets can then harbor anaerobic bacteria, including key culprits like Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia, and Treponema denticola. These microbes release substances like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and proteases that fuel inflammation by increasing levels of interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α).

This inflammatory response doesn’t stay localized. Bacteria and their toxins can enter the bloodstream, leading to transient bacteremia and potentially spreading throughout the body. This systemic inflammation is thought to prime the brain’s immune cells, setting the stage for neuroinflammation associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Studies have even found links between elevated biomarkers like alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and both severe periodontitis and reduced cognitive function.

How Pathogens Invade the Brain

Oral pathogens possess sophisticated ways to reach the brain. They can directly breach the blood-brain barrier or travel along cranial nerves, particularly the trigeminal nerve. The bacteria’s virulence factors, such as gingipains produced by P. gingivalis, along with their outer membrane vesicles, can compromise the integrity of this protective barrier. Once inside, they can activate immune cells in the meninges and brain tissue itself.

Indirectly, the chronic systemic inflammation caused by periodontitis primes the brain’s resident immune cells, the microglia. When exposed to bacterial products like LPS, these cells activate signaling pathways (NF-κB and STAT3) that lead to the production of inflammatory molecules. These inflammatory signals can then intersect with the biological processes underlying Alzheimer’s disease. Research suggests that LPS and gingipains might contribute to the buildup of amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques, a hallmark of AD. Furthermore, these factors can promote the hyperphosphorylation of tau protein, another key player in neurodegeneration, potentially through the activation of enzymes like GSK-3β.

What the Research Shows

A growing body of evidence links chronic periodontitis to an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Large-scale epidemiological studies have consistently reported a higher incidence of dementia and AD among individuals with periodontitis. Some reviews suggest this risk could nearly double. Animal models further support this connection, showing that oral infection with Porphyromonas gingivalis can accelerate the production of Aβ42, trigger neuroinflammation, and lead to damage in the hippocampus. Promisingly, preclinical studies using gingipain inhibitors have demonstrated a reduction in brain bacterial load, inflammation, and Aβ42 levels, suggesting a protective effect.

Moreover, analysis of post-mortem brain tissue from individuals with AD has revealed microbial signatures, including Porphyromonas gingivalis. The identification of gingipains, key enzymes from this bacterium, in AD brain tissue further strengthens the biological plausibility of this oral-brain axis. While observational studies and variability in case definitions mean causality is still under investigation, the combined findings paint a compelling picture.

Protecting Your Brain Starts With Your Gums

The implications for prevention are clear and actionable. Maintaining excellent oral hygiene throughout life is a simple yet powerful strategy for supporting brain health. This includes brushing twice daily with fluoride toothpaste, cleaning between your teeth daily, avoiding tobacco, and attending regular dental check-ups and cleanings.

For those with existing periodontitis, prompt and effective treatment is key. This typically involves scaling and root planing, followed by regular maintenance cleanings. Researchers are also exploring adjunctive therapies like probiotics and host-targeted anti-inflammatory approaches. It’s vital for primary care physicians and neurologists to integrate oral health screenings into routine check-ups, especially for individuals in midlife and later years. Asking about gum health and referring patients for dental evaluations can help identify those at higher risk.

For individuals already living with dementia, simplifying oral hygiene routines is essential. This might include using an electric toothbrush with high-fluoride toothpaste and ensuring caregiver assistance. Prompt treatment of active gum disease and consistent reminders can help manage the condition.

Unanswered Questions and Future Research

Despite the mounting evidence, several crucial questions remain. The most significant is establishing the direction of causality: does gum disease drive Alzheimer’s, or does cognitive decline lead to poorer oral hygiene? Human studies also suffer from inconsistencies in how periodontitis and cognitive function are defined and measured, along with potential confounding factors like age, diabetes, and smoking. More robust, long-term studies are needed to clarify these complexities.

The Path Forward: Targeted Therapies

Future research efforts are focusing on developing precision antimicrobials that can target specific periodontal pathogens without disrupting the beneficial oral bacteria. Inhibitors of P. gingivalis gingipains are a leading area of interest, as are compounds that block bacterial communication (quorum sensing) and biofilm formation. The development of localized treatments, such as topical applications, could enhance effectiveness within gum pockets while minimizing systemic side effects.

Beyond antimicrobials, researchers are exploring host-immune modulators to calm inflammation in both the gums and the brain. Success in this field will require close collaboration between dental professionals, neurologists, microbiologists, and public health experts to integrate oral care into broader brain health strategies.

What Does Gum Disease Have to Do With Alzheimer’s?

References

- Seyedmoalemi, M. A., & Saied-Moallemi, Z. (2025). Association between periodontitis and Alzheimer’s disease: A narrative review. IBRO Neuroscience Reports, 18, 360–365. DOI: 10.1016/j.ibneur.2024.12.004.

- Bhuyan, R., et al. (2022). Periodontitis and Its Inflammatory Changes Linked to Various Systemic Diseases: A Review. Biomedicines, 10(10). DOI: 10.3390/biomedicines10102659.

- Li, R., et al. (2024). The oral-brain axis: can periodontal pathogens trigger Alzheimer’s disease? Frontiers in Microbiology, 15. DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2024.1358179.

- Cichońska, D., et al. (2024). Periodontitis and Alzheimer’s disease—a narrative review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(5). DOI: 10.3390/ijms25052612.

- Brahmbhatt, Y., et al. (2024). Association Between Severe Periodontitis and Cognitive Decline. Life, 14(12). DOI: 10.3390/life14121589.

- Barbarisi, A., et al. (2024). Periodontitis and Alzheimer’s disease: A review. Dentistry Journal, 12(10). DOI: 10.3390/dj12100331.

- Haque, M. M., et al. (2022). Advances in novel therapeutic approaches for periodontal diseases. BMC Oral Health, 22(1). DOI: 10.1186/s12903-022-02530-6.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Sep 10, 2025