In 1913, the poem “In a Subway Station” by the American poet Ezra Pound was published in the United States.Toshort and withimaginary. Sstarted poet wrote something in thirty lines, then began to thoughtfully (or not so thoughtfully) cross out line by line until he left two, fourteen words in total. According to Pound, he tried to capture that moment when something external and objective turns into internal and subjective. Here is the poem:

These faces appeared in the faceless crowd. There were leaves on a black damp branch.

Does it remind you of Japanese haiku? Not without reason. Pound felt what and to what extent to take from the Western tradition, and what from the Eastern, in order to create new, a poetic gesture in tune with that time. There is a feeling that he was fascinated by exactly the Japanese spirit and art as the modern average Russian reader sees it. INDid Pound hardly know that at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries (by the standards of history – just now) his English-speaking colleagues in the person of Shakespeare, Byron, Longfellow and others burst into the territory of Japan, which had opened up to the world and brought itor The fallen literary world is in turmoil.

For centuries, Japanese poetry was in a mothballed state: writing, compiling poetry collections, competitions – well, that’s all – was a bothersome formality. The stagnation of the poetic process was partly helped by the eclectic religious views of the Japanese: since everything in the world is fleeting and transitory, it is necessary to record the eternal, and expressing oneself in art and poetry is a futile exercise. Japanese poets have become accustomed to repeating the same cliches and images for centuries and quoting recognized masters of the past. You, too, involuntarily feel respect for your interlocutor when he easily and appropriately manages to throw in some quotation from Khlebnikov? To those Japanese, far from us, such feints seemed very cool. Ready-made lists of seasonal words were also compiled, which necessary was to use. Yes, there were problems with diversity.

The Meiji era began in 1867: V countriesis, sitting for centuries in feudal self-isolation, startedindustrializationI. Under the influence of Western trends, economics, politics, culture and literature began to change. The Japanese began to read and translate European authors. And here we are alone, having abandoned ouror heritage, in an ecstatic impulse they raised Western poetry to the shield: “TOHow can you write these outdated tanks and haiki, because they cannot accommodate all the shocks and problems of modern Japanese!” They lacked Punda’s sense of proportion. In opposition, of course, were the bone “Japanophiles”: «traditions are above all, we must preserve “Japaneseness” at all costs and not succumb to the harmful Western spirit!” Meanwhile, the now well-known short poetic form of haiku fell asleep.orin death sleep and waited for the savior to appear and awaken heror from sleep.

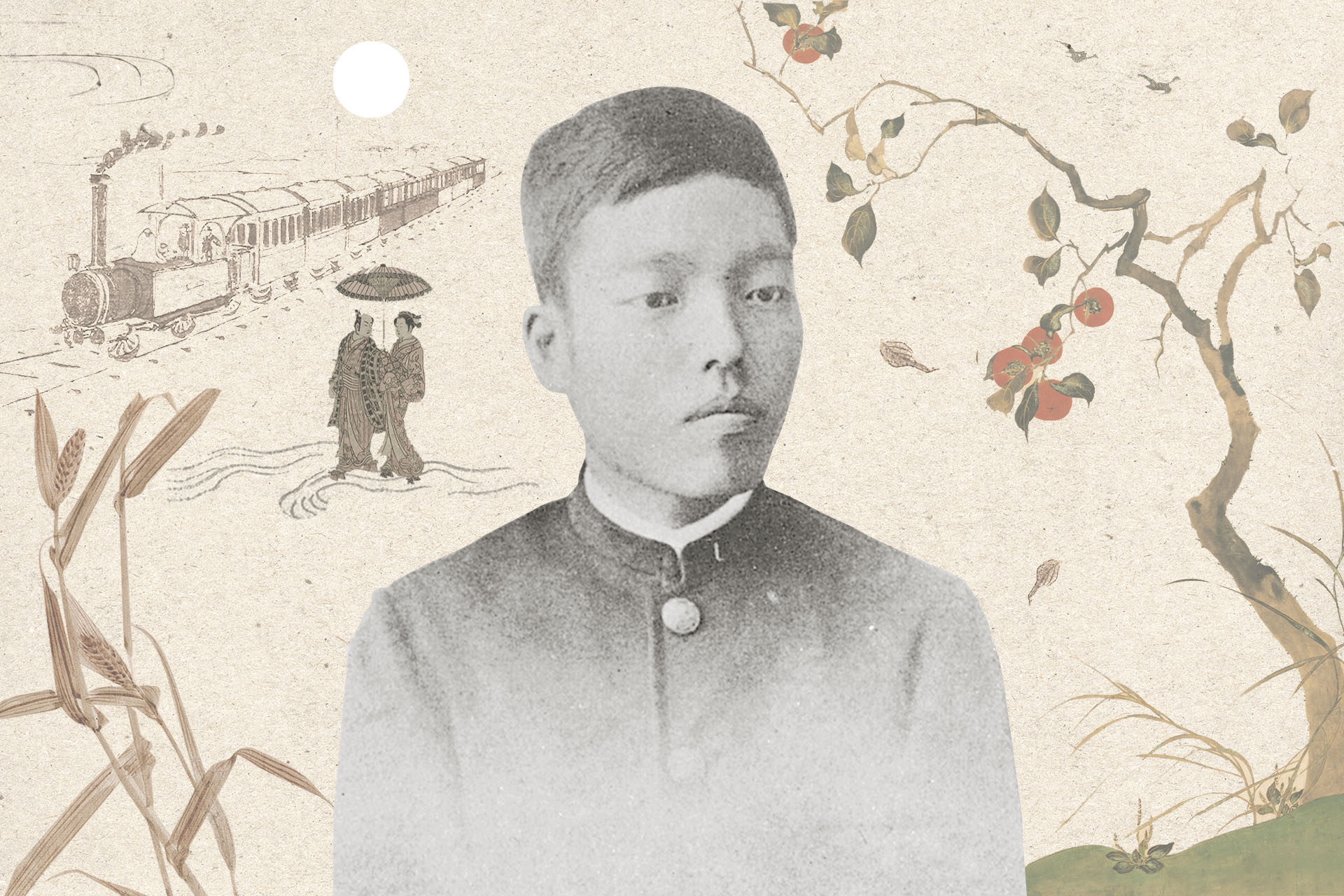

And how symbolic: in 1867, the poet Masaoka Shiki was born in Japan. There was little exciting in his life: he suffered from tuberculosis and, due to problems with the spine, spent part of his life bedridden (in this context, his later poems are especially poignant). He was not ashamed of his illness and did not hide it. “Shiki” is nothing more than a pseudonym – a Chinese-Japanese reading of the word “cuckoo”, which, according to legend, coughs up blood when it sings. Such is self-irony. But that’s not what interests us.

The Haiku’s Unexpected Revival

IN traditional Japanese poetry hasorm, undeniably disarming and demanding to be carefully preservedIwhether: eThat a hint For Japanese poets of utmost importance convey the invisible; The main thing is not what is written, but what is unspoken, what lies beyond the words. WellIf you express feelings too fully and clearly, it will disappear a secret Japanese art. And moreor – there should be nothing superfluous: need to focus on one thing. TOAs Yasunari Kawabata said: “One flower conveys the floweriness of a flower better than a hundred.”

Masaoka Shiki deeply understood not only the shortcomings of Japanese poetry, which threatened to reduce itor to the grave, but alsoall its charms. His revolutionary spirit was manifested precisely in his ability to balance. For example, calling to get rid of the idol Basho, in the same article he directly talks about why he respects him. Western realism taught Shiki to use his direct observations. This is how the principle of “shasey” appeared. Shiki argued that mindless repetition of the same clichés should be left in the past. The artist looks at nature and writesor as he sees, and not as the canons prescribe.

Of course, Shiki did not demand blind copying, but insisted on honesty and accuracy of perception. However, he himself did not immediately implement this principle. Let’s takeorm his poem from 1886:

Let him not rush to let the whole shaggy cherry bud blow into the wind.

Here an unspoken comparison is made between the shaggy eight-leaf cherry blossom and the regular one. Prichorm ordinary sakura falls gradually, petal by petal, but it is useless to beg eight-leaf sakura to do the same – it fades immediately. Shiki couldn’t help but know about this, but for beauty’s sake made this assumption. And here is his haiku from 1895:

Sowing wheat – The mulberry trees put their branches together.

Tut the shasei principle is implemented. Since mulberry trees grow next to wheat, duringor sowing their branches were tied together (so as not to interfere). Maybe, They still do that now.

Moreor Shiki developed the concept of two types of beauty: Eastern (passive) and Western (active). Ohe sought to combine the contemplative nature characteristic of Eastern beauty with the dynamism and expressiveness of Western beauty. INlocked in his own texts imagery, themes and vocabulary not previously considered suitable for classical poetry: for example, mentionsl about steam locomotivestooth powders and telegraph poles – about everything that allowed to reflect modern life. However, the most striking radical proposals of Shiki and his students were rarely implemented in practice. Sunor– Shiki wasn’t a nihilist, so some everyday objects and realities you still can’t find it in their poetry. For example, in collections of his poems can’t find not a single locomotive. WITHthere are several poems with a railway station (below is not one text, but five separate ones):

Look, the scarf hangs lonely on the station bench! The lotus is blooming, And the station is empty In the summer silence. The autumn rain is pouring. Two people at the station are waiting for the train to arrive. The Station is famous for the fact that they sell Persimmon here in the fall. At the station, a single fan was forgotten.

The example of these poems shows that Shiki does not refuse to use seasonal words (each poem has a marker of the season), that is, not an impulsemeat with poetic canons completely. Almost all of them melancholic, permeated motive of loneliness, abandonment. Except that the poem about persimmons looks more like a humorous sketch (a separate article can be written about Sika’s love for persimmons).

Baseball, Persimmons, and a Poet’s Mortality

Here’s what What really cannot be found in the collective Basho and Issa is this baseball. Masaoka Shiki is considered to be the first baseball fan in the ranks of high-kite sportsmen.. MYou can even google an article in which he explains the rules of the game and translates the names of baseball positions and other specific vocabulary into his native language. He is even credited with the phrase “baseball is the most exciting and noble of all wars.”

Summer herbs! The baseball players are getting further and further away. Everything is overgrown with grass. Only the road to the baseball field turns white.

In the famous play by Tom Stoppard, Rosencrantz’s buttorquestion: “TOwhen a person realizesort your mortality?»And myself same answers it: at birth. But Janine Beichman, outlining Siki’s biography, believes that the turning point in the poet’s sense of death occurredorl in adulthood. Shiki planned to work as a war correspondent during the First Sino-Japanese War, andorBy that time I already had tuberculosisorzom. According to Beichman, until the very moment of his departure, Siki was in high spirits and spouted phrases in such a way that let’s say samurai spirit. Mthe idea that death may befall him too, etc.I was just coming at that moment, as the train taking him to Hiroshima (from there he was to sail to China) set off from the Tokyo station. Then the poet was overtaken by an unbearable feeling of loneliness. INplay soon endedbut insights of this kind, of course, are not pass without a trace. And his condition worsened. B 189In the year 6 he composed the following poem:

The fruits are falling – And now the neighbor’s children are running past.

Also a cast of life. In the summer, the neighbor’s children, hiding from the heat, came into Siki’s house to play, and in the fall they were able to spend more time outside. In this “they run past”” – All the loneliness of the poet, which wanders from haiku to haiku. And here is one of the last poems from 1901. About persimmon. But not really about persimmons:

To enjoy persimmons I have the last year left – A thought dawned on me.

Masaoka Shiki was not a nihilist. NHe wasn’t Vvedensky, he didn’t write with a ladder — in short, he was not shocking to the same extent as our “silver” poetsbut still allowed me to look at the world of Japanese poetry from a slightly different angle. You can ask: “Well, I allowed it. So what?”

In 2026 in Russia I still meettsya two readerlyX approach. Some people certainly believe in the genius of the collective poet Basho. “Let them believe» — you will say, however this is resignedm adoration sees the destructive passivity of feeling. For others, the collective Basho is something a priori unknowable. Such a view of Japanese poetry and art already leads to a vulgar renunciation of any attempt toor it’s latet: “I’m in the house”

And here we return to Ezra Pound: ohbut he didn’t just write a beautiful poem, But saw in this alien poetic tradition something familiar. I recognized myself in her. If you don’t recognizeorIf you find yourself in Basho, then try to look into the face of Masaoka Shiki.