Donald Campbell is the son of Sir Malcom Campbell, a legend in the world of racing and, above all, of speed records, both on water and on land, with his famous “Blue Bird” or “Blue Bird”, a name that He was born when one day in 1912, he saw Maurice Maeterlinck’s play “The Blue Bird” at London’s Theater Royal Haymarket. He was so inspired by the theme of the performance, the pursuit of happiness, that he ran out of the theater as soon as the curtain fell, waking up the local hardware store owner to buy the store’s entire stock of blue paint. That night he christened his racing car “Blue Bird” and with the paint still wet, the next day he won his first race at the famous Brooklands circuit in Surrey.

This paternal inheritance of being the fastest encouraged Donald from his childhood, but the path would not be easy. It was all a job of self-improvement because the young Donald suffered violent episodes due to a rheumatic heart disease that banned him from all violent sports. Thus, he initially worked in an office. Come World War II, he was about to become an RAF pilot when another of his crises struck and he was cut off from his desire to fly.

Instead, business is going well. Once the conflict is over, he sets up a tool factory, which is a complete success.

family honor

Around midnight on December 31, 1948, Sir Malcom Campbell died of a heart attack. And three months later, Donald, in conversation with a family friend, finds out that an American named Henry Kaiser wants to beat his father’s record, 228,010 km/h on water with the “Blue Bird K3”, which dated from the year 1939. Donald recounts that he leaned back in his father’s favorite chair and “suddenly I felt angry, the next moment I was thinking that I would have a chance to improve the record myself.”

So he decides to reuse the last boat with which his father thought to break a new record at the end of the war. It was the “Blue Bird K4”, although instead of the turbine engine of this one, Malcom wants to use the old piston ones from the K3. But it turns out that these had been sold to a dealer and his recovery costs him a significant sum and the delivery of the Blue Bird of records on paternal land, which he had inherited.

On June 26, 1950, the American Stanley St. Claire Sayres, reaches 257,960 km/h with his boat “Slo-mo-shun IV”, one more motivation for Donald Campbell who is willing to recover the family honor, starting like this his “recordman” career.

With his father’s refurbished “Blue Bird K4″ (renamed Bluebird”), he makes an attempt in 1951, but a structural failure at 270 km/h over the waters of Lake Coniston puts an end to everything.

While another Englishman enters the fight. This is John Cobb, who is going to try to break the record with his “Crusader”, with a radical design inspired by aeronautics. On September 29, 1952, at Loch Ness, while going 210 miles per hour, about 338 km/h, the boat disintegrated and Cobb died. In 1954, the Italian Verga will also perish trying to beat the American’s record.

Donald Campbell with his K7, a real plane on water

In 1955, after having overcome many difficulties and with the new “Bluebird K7” built by the brothers Ken and Lewis Norris (provided with a Metropolitan-Vikers Beryl jet engine), Donald Campbell managed to reach 325.590 km/h, achieving thus being the fastest man in the world on water… And he will continue to break his own record year after year until, in 1959, he reaches 418,990 km/h.

on land

Now, like his father, Donald Campbell is made a Knight of the British Empire and he is drawn to being the fastest on land as well: the goal is to reach 400 miles per hour, more than 400 mph.

After multiple operations, he manages to collect the brutal sum that the construction of his new “Blue Bird” on wheels entails, no less than 150 million pesetas at the time. The construction of the car is also entrusted to the Norris brothers (50 other British companies collaborate or support its construction), and a Bristol-Siddeley Proteus turbine used in the Bristol Britannia airplane is chosen as the engine: no less than 4100 CV of power for move the 4,320 kilos of weight.

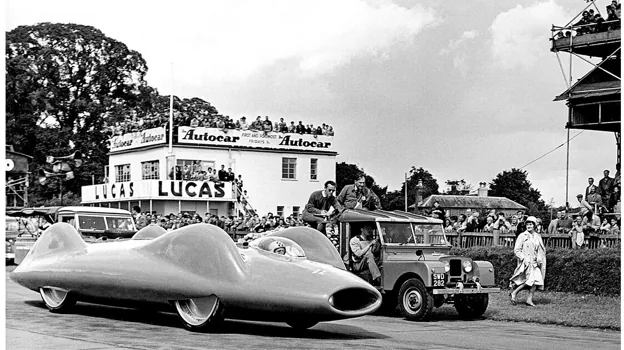

The Bluebird Proteus, during a presentation in England ahead of Donald’s first land record attempt

On September 16, 1960, Campbell gets behind the wheel of the American Bonneville Salt Lake. When it is close to 600 km/h, the car takes off and falls again, bouncing off the ground three times. Leo Villa (the faithful engineer-mechanic and friend of the Campbell family) and Ken Norris run, fearing the worst, to the scene of the accident. To his surprise, although the car is badly damaged, it has held up quite well and even its engine is still running. Miraculously, Donald is alive and, based on the violence of the impact, sustains relatively minor injuries, the most serious being a fractured skull. And he promises to try again.

Hearing this, Sir Alfred Owen (the owner of the BRM Formula 1 team) exclaims: “…if Campbell has the guts to try again, I’ll build him a new car.” The structure of the “Bluebird” was so strong that almost 80% of the car can be reused. However, significant aerodynamic changes were incorporated, most obviously a large vertical tailfin, to improve stability.

At the end of 1962, the car was ready again. By then, Donald had decided that a new framework was required for the attempt. The oil company BP, one of his sponsors, set out to search the world for a new site. From his selection, Donald chose Lake Eyre in South Australia, a large dry salt pan in a very remote location, approximately 700 km north of Adelaide, with 32 usable kilometers instead of the 18 of the American lake. It rarely rains on Lake Eyre, but when Donald showed up in 1963, the heavens opened up. And that same year it rained again, a situation that was repeated in 1964. Most of his backers had withdrawn from the project by then, so Donald was using mainly his own money to finance the attempt. On the morning of July 17, 1964 the weather had improved…

Everything ready to break the record: after the accident many aerodynamic changes were made

The track was not in a very good condition. The two roundtrips required to certify the record put the tires, the structure of the car and the courage of the driver to the test. But when it was all over, Donald Campbell, at 648,728, was the fastest man on earth in a classic transmission (wheel drive, not jet) car.

and back to the water

In Australia, on December 31, 1964, late in the afternoon, Donald broke his own water speed record with a speed of 276.33 miles per hour, 444.615 km/h. He thus became the only man to break the speed record on land and water in the same year. His attention then turned to a new project, building the Bluebird CN8, a rocket-powered car redesigned by the Norris brothers with an estimated top speed of over 850 miles per hour, 1,352 km/h.

But while work was underway on CN8, he wanted to make one more attempt to break his own water speed record. On the morning of January 4, 1967, at Lake Coniston in England, on the outbound journey, all had gone well.

Now it was time for the return route, necessary to homologate the record. It’s 8:51 in the morning when the jet engine roars as it pushes the K7 past 300 miles per hour. Suddenly, the boat rises and explodes… Malcom Campbell and the “K7” disappear forever under the waters of Lake Coniston.

The “K7” over the waters of Coniston

In October 2000, the project team called “Bluebird” led by diver Bill Smith, exploring the bottom of the lake, found pieces of “K7”. New remains are added and, on May 28, 2001, the body of the pilot appears.

Today Sir Donald Campbell is buried in Coniston Cemetery. And very close, in the Ruskin museum in Coniston, the reconstructed K7 donated on December 7, 2006, by Gina Campbell, Donald’s daughter, is exhibited.

But it is looking at the calm waters of the lake where you can see reflected the dream of that young man who wanted, like his father, to be the fastest.