THE International Space Station (ISS) He constantly faces the dangers of being outside the atmosphere, but lately the human factor continues to give him headaches. The reason is the growing number of space debris in orbit. So much so that it was known that, in less than a week, he had to carry out two maneuvers avoid collisions with debris in its path. A drama that, it seems, will be almost a constant from now on.

The latest occurred last Monday, November 25, when the Russian ship Progress 89 It fired its thrusters for three and a half minutes to divert the station from a piece of space debris. This maneuver raised the Space Station’s orbit by about 500 meters. It may not seem like much, but in terms of space and having to expend energy it is something very relevant.

This incident comes in addition to another maneuver carried out on November 19, when the same vessel mentioned above burned fuel with its thrusters for five and a half minutes to dodge a fragment of a weather satellite defense that disintegrated in 2015. Come on, it’s almost Groundhog Day for astronauts.

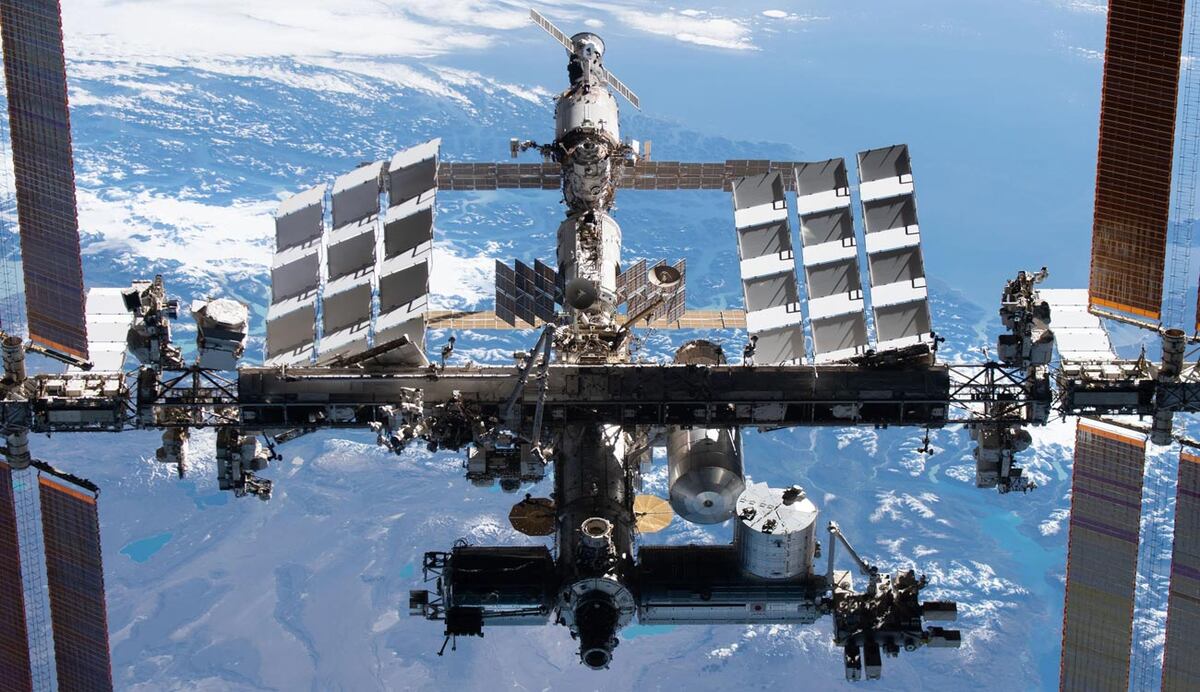

Space station part of NASANASA

Space debris already poses a big risk

Space debris poses a very serious threat to the ISS, as has been demonstrated. Even the smallest objects, traveling at high speed, can cause significant damage to the station’s structure – or endanger the safety of its crew. This problem it is especially severe in low Earth orbit (LEO)where the Space Station operates, which has become increasingly congested due to the increase in satellite launches and the remains of previous space missions.

This phenomenon has generated concern in the scientific and space community since it could not be otherwise. However, the Practical solutions to address the problem are quite limited and therefore, for the moment

As more and more satellites are launched into space, the risk of collisions increases. This phenomenon can trigger a cascade effectknown as the Kessler syndromewhere each collision generates even more pieces of debris which, in turn, increase the risk of future collisions. This cycle threatens the sustainability of space operations in Earth orbit.

How the danger to the Space Station is managed

To minimize the risk, NASA and its international partners constantly monitor space to detect and predict potential threat trajectories. Organizations like the European Space Agency (ESA) and the United States Department of Defense They provide key data to decide when to take evasive maneuvers. However, these measures are reactive and do not address the root of the problem.

The space community has proposed various solutions to address this challenge, including:

- Deorbit of deprecated satellites: implement mechanisms that allow decommissioned satellites to re-enter the atmosphere in a controlled manner, where they safely disintegrate.

- Stricter rules: establish international standards that control both the launch process and the dismantling process of satellites at the end of their useful life.

- Active Removal Technology: design devices capable of capturing and removing space debris from the most congested orbits.

THE international collaboration It will be crucial to manage this problem responsibly, as space debris does not respect borders and affects all nations operating in space, so the solution must be a joint effort. And a clear example is the gymkhana that the International Space Station had to carry out recently.

International #Space #Station #Lifestyle #Intelligent #life

How can international cooperation help in managing the space debris crisis?

Interview Between Time.news Editor and Space Debris Expert Dr. Emily Carter

Editor: Welcome, Dr. Carter! It’s great to have you with us today. You are an expert in space debris, and as we’ve seen with the recent maneuvers required by the International Space Station (ISS) to avoid collisions, this is quite a pressing issue. Can you start by giving us an overview of just how severe is the threat posed by space debris to the ISS?

Dr. Carter: Thank you for having me! The threat of space debris to the ISS is indeed significant. As you mentioned, even small pieces of debris can travel at incredible speeds—often exceeding 28,000 kilometers per hour. At that velocity, even a tiny screw or fragment can cause catastrophic damage to the station’s structure, which is critical for protecting the crew on board. The situation is particularly critical in low Earth orbit (LEO), where the ISS operates. This area has become increasingly congested due to a surge in satellite launches and remnants from previous missions.

Editor: That does sound alarming. The ISS recently had to perform two collision avoidance maneuvers within just a few days. What do these maneuvers entail, and how challenging are they for the crew and the spacecraft?

Dr. Carter: These maneuvers require the ISS to change its orbit slightly to avoid potential collisions. For instance, the maneuver on November 25 involved firing the thrusters of the Russian Progress 89 for about three and a half minutes, raising the station’s orbit by about 500 meters. While that seems small, it matters significantly in terms of energy consumption and mission planning.

The crew must remain alert and be prepared to execute these evasive actions at a moment’s notice, which adds stress to their already demanding schedules. Continuous maneuvers can disrupt science experiments and daily routines on board, so there is a lot to juggle.

Editor: Speaking of disruptions, you mentioned that this could become a regular occurrence. Could you elaborate on why the frequency of these maneuvers is increasing?

Dr. Carter: The frequency of avoidance maneuvers is increasing largely due to the rapid growth of space traffic. With the rise of satellite deployment—especially with companies launching large constellations for internet services—the risk of collisions is climbing. This situation brings us closer to what we fear: the Kessler syndrome. This is a cascading effect where collisions generate more debris, each of which creates further risks for future spacecraft. It’s a cycle that could threaten the long-term viability of space operations.

Editor: That’s a troubling prospect. What are some practical solutions that the space community is discussing to tackle this growing issue of space debris?

Dr. Carter: Unfortunately, there are no simple solutions at this point. Various ideas are on the table, such as improving tracking and monitoring systems to better predict and avoid potential collisions. Some concepts involve actively removing larger debris through methods like nets or harpoons, but these projects are still largely experimental. Another proposed solution is “design for demise,” where future satellites are built to burn up upon re-entry instead of leaving behind debris.

However, the challenge is that many existing pieces of debris can’t be removed easily, and as long as new satellites continue to be launched without proper end-of-life plans, the risk will remain high.

Editor: It sounds like a multifaceted problem that requires global cooperation. How can countries and companies collaborate to mitigate the risks associated with space debris?

Dr. Carter: Absolutely, international cooperation is crucial. We need agreements on best practices for satellite launches, operational procedures, and end-of-life disposal. There are also institutions like the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee, which promote guidelines for all spacefaring nations to reduce debris generation.

Moreover, sharing tracking information and investing in joint debris monitoring systems could lead to more effective collision avoidance strategies. With the increasing commercialization of space, it’s vital that companies also prioritize responsible practices to protect the long-term sustainability of space exploration.

Editor: It seems clear that as we push further into space exploration, we must be wise stewards of our orbital environment. Thank you, Dr. Carter, for shedding light on this critical issue. It’s been a pleasure discussing the dangers of space debris and what we can do to address it.

Dr. Carter: Thank you for having me! It’s important to keep this conversation going as we look toward the future of space activities.