On a rainy and stormy day about 77 million years ago in what is now southeastern Alberta, Canada, a certain dinosaur was having a hard time.

He Centrosaurus opened An adult, a medium-sized herbivorous cousin to the larger Triceratops that lived alongside Tyrannosaurus, it had a advanced malignant bone cancer on the shin The cancer had possibly spread to other parts of her body and is almost certainly believed to be terminal.

But probably this Centrosaurus did not die from bone cancer, because before this could happen, he and the thousands of others Centrosaurus in his herd were struck down by a catastrophic flood, possibly caused by a tropical storm.

Millions of years later, the bone bed preserved after this mass die-off event helped provide important evidence that these dinosaurs moved in huge herds.

But the diagnosis of osteosarcoma This particular dinosaur—a rare malignant bone cancer most commonly found in children and diagnosed in about 25,000 people per year worldwide—only occurred in 2020.

It was the first time a malignant cancer had been diagnosed in a dinosaur and required a multidisciplinary team to confirm the case.

“It turns out that the diseases that affected the dinosaurs essentially have the same appearance as those affecting humans or other creatures,” says Bruce Rothschild, research associate in vertebrate paleontology at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pennsylvania, United States.

The results of this and other research are revealing previously unknown details of how dinosaurs lived and died. Some argue that they could also provide new insights into diseases that still plague us today.

a peculiar find

The quest to accurately diagnose a dinosaur with bone cancer began when David Evans, a paleontologist at the University of Toronto and curator of the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada, met Mark Crowther, a human hematologist and chair of the University’s medical school. McMaster, in Canada.

They realized that they could use their combined experience to try to find an osteosarcoma.

Still, finding a potential case was no easy task. Pathologies are often seen in fossil specimens, but they’re not really organized according to this characteristic, Evans says. In contrast, bones with the characteristics of the disease are usually distributed throughout all collections.

After examining hundreds of bones at the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Drumheller, Canada, along with several other scientists, including Snezana Popovich, a bone pathologist at McMaster University, they recognized the possible signs of bone cancer in the shinbone of the Centrosaurus opened.

“I’ll definitely remember Snezana picking up this bone and saying, ‘I think this is bone cancer,'” he recalls.

The bone had a bulge at one end that was labeled as a fracture callusbut even at first glance it had several telltale signs of bone cancer: it was visibly malformed and had large, unnatural foramina (open holes) around the lump.

The team used every means they had to confirm a diagnosis in their 77-million-year-old patient.

They compared the bone to both a pimple Centrosaurus normal as with a human calf bone with a confirmed case of osteosarcoma.

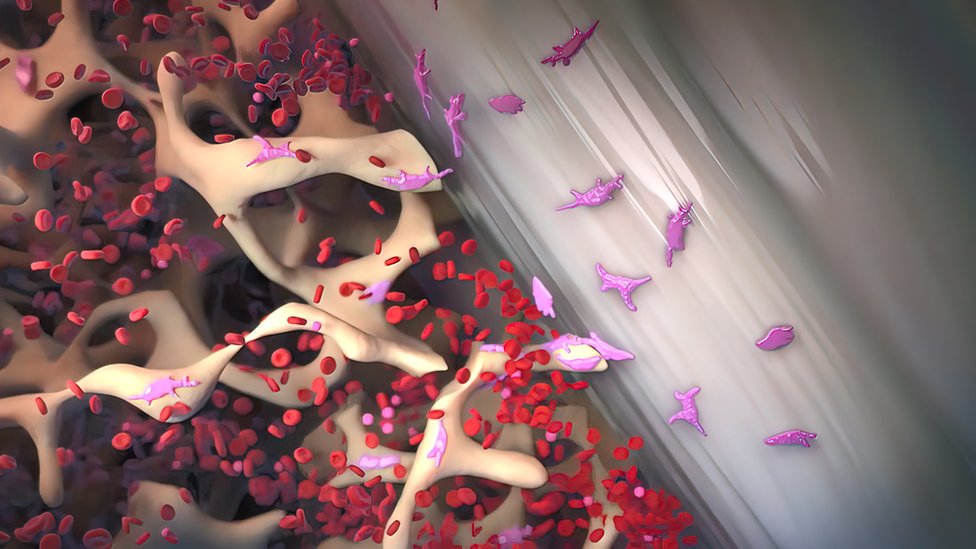

But they also used rX-rays, high-quality computed tomography (CT) scans along with 3D reconstruction and histology tools to create biopsies to be able to study it at the cellular level.

“That allowed us to make a positive cancer diagnosis that is on par with what the doctors on my team suggested. [que harían] in a human patient,” says Evans.

“We actually set out to serially section the bone… We were able to track the cancerous tumor working its way through the bone from the knee to the ankle.”

New focus

The difference with the diagnosis of live animals today is that for dinosaurs there is very little material to investigate apart from fossilized bones and other hard tissues such as teeth and sometimes skin, feathers or hair.

“Anything where only part of the diagnosis is bone, that’s really difficult,” says Jennifer Anné, senior paleontologist at the Children’s Museum in Indianapolis, USA.

“Since we have such limited information that we can use, those limited clues, we are the MacGyvers: we try everything we have to try to crack this information.”

Bone is often one of the least studied parts of biology, he adds. “Whereas in paleontology all we have are bones. So we know all about the bones.”

Diagnosing any type of disease in a fossil record is incredibly difficult, agrees Cary Woodruff, curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Phillip and Patricia Frost Museum of Science in Miami, Florida.

“We really can’t trust any of the medical tests that we would do today… The way we identify [enfermedades] It has to be radically different.”

Woodruff, who specializes in sauropods, huge, long-necked plant-eating dinosaurs like Brachiosaurusalso collaborated with veterinarians and doctors in his recent work to diagnose a dinosaur respiratory infection for the first time.

He had noticed something odd about a 150-million-year-old diplodocid sauropod specimen named Dolly: a lumpy, irregular growth on her vertebrae that had fossilized into the shape of a broccoli.

“I knew enough to know that what I was looking at was not normal, but not enough to be able to identify what I might be looking at,” he says.

He posted a photo on social media asking if anyone had seen something similar or knew what it could be, and quickly received a flood of responses, including from his future co-authors.

“The general response from the experts was, oh my gosh, we’ve never seen this before, but this is exactly what we would predict a respiratory infection would be in a sauropod“he adds.

The team he assembled began to investigate all the diseases that could have caused this growth. “It’s just as important to eliminate what it isn’t sometimes certainly in the first few passes as it is to help you focus on what it is,” says Woodruff.

They realized there were bumps in the exact areas of the bone that would have attached to Dolly’s air sacs (the air-filled structures still found in birds today and often become infected and cause the respiratory disorder airsacculitis).

“They were similar enough that to suggest that Dolly’s diagnosis was air sacculitissays Woodruff. “The ‘broccoli’ fossil that came out of […] it was a secondary bone infection.”

It is impossible to say what might have caused this infection as, for obvious reasons, the team was unable to run any blood tests on Dolly. However, the most common cause in living dinosaurs, today’s birds, is breathing in fungal spores.

“Most likely, this could have been what happened in our dinosaur 150 million years ago,” says Woodruff. “We know that fungi have a ridiculously long evolutionary history, it would have been an important component of these environments as well.”

Ailments that leave no trace

There are also many ailments and diseases that leave no trace in what’s left of the dinosaurs, so in most cases it’s hard to know what killed them.

“Probably a good part of our dinosaurs died from diseases or things like that, for which we don’t have osteological evidence, so there are no indicators in the bones,” Woodruff says.

Still, as science advances, we can get better at recognizing clues that point to certain diseases. “There may be a lot of bones that have diseases that are barely visible on the surface that no one would even think to look at.“, dice Evans.

The more diagnoses are made, the more information paleontologists can learn about how these dinosaurs lived.

For example, advanced osteosarcoma of the Centrosaurus opened would likely have affected his movement, making him a prime target for a Tyrannosaurusthe top predator at the time, says Evans.

Instead, however, he appears to have died with his pack in a natural disaster, indicating that maybe this one wasn caring and protectingsays Evans. “It’s a really interesting and unique insight into dinosaur life that we didn’t have before.”

an unexpected benefit

But the discoveries could also contribute to our modern understanding of disease. Rothschild, a rheumatologist, has used his analysis of hadrosaur fossils to help distinguish between osteochondritis and osteochondrosis, two different but similar-looking bone conditions.

Evans was even invited to participate in a US Osteosarcoma Institute symposium that focuses on finding a cure for the disease. “[Había] a group of the best bone cancer specialists from around the world [allí]and then there was me with the dinosaurs,” says Evans.

His article had diagnosed a giant tumor in exactly the same place where you would expect to find the disease in a human being. “It gives us some perspective to think about how old these diseases are.”

A cast of the original Centrosaurus apertus shin with osteosarcoma was also part of the exhibit. Cancer Revolution last year at the Science Museum in London.

“We wanted to show that cancer is not a uniquely human or modern disease,” says Katie Dabin, lead curator of the exhibition. “Dinosaurs seemed to be a shining example that cancer has been present in multicellular organisms for a long time.”

Evans hopes her paper will attract clinicians, researchers and experts interested in collaborating with paleontologists and vice versa, leading to other findings on rare diseases that can be found in the fossil record.

“Who knows where those discoveries could lead?he says. His team is already working with another group of researchers who believe they might have found evidence of osteosarcoma in a meat-eating dinosaur.

But there’s also something about diagnosing these diseases in dinosaurs that just helps us relate to them better, Woodruff says.

“You can hold that dolly bone [el diplodocus] 150 million years old on your hands and seeing those signs of infection caused by some kind of respiratory disorder, you know that 150 million years ago Dolly felt horrible when she was sick like we all do when we’re sick with similar things.

“And I think that’s fascinating.”