The negotiations for the capitulation of Granada were closed at the end of November 1491. The fall of the last Muslim enclave in Western Europe, after ten years of war between the Nasrid dynasty and the Crown of Castile, with thousands of deaths involved, seemed compensate for the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks in 1453 or the occupation of Otranto in 1480. Pope Innocent VIII himself went to the church of Santiago de los Españoles, in Rome, to officiate a victory celebration mass.

The end of the almost eight centuries of Muslim domination in the Iberian Peninsula was celebrated throughout Europe. The meetings to establish the conditions for the delivery of the city were held in the Alhambra, where the Castilian negotiators secretly went before returning to the camp at dawn. Contrary to what had happened in the times of her father Juan II and her brother Enrique IV, Queen Isabella I of Castile wanted to put an end to Islamic power once and for all, but trying to avoid at the last moment an assault on the city in which much unnecessary blood would have been spilled.

The final episode, therefore, was free of violence and sought to preserve the city intact, which at that time was undoubtedly one of the most fertile and important on the Peninsula, inhabited by more than 40,000 residents who enjoyed homes and comforts. uncommon at that time. The Catholic Monarchs went further and decided to respect their customs, institutions and beliefs, as well as offer tax exemptions and safe conduct to all those who wanted to go into exile, in exchange for surrendering the capital without putting up any resistance. The Monarchy did not want the defeated to prostrate themselves before the conquerors.

That was the reason why the Kings avoided entering Granada with armed men and occupied, at first, only its walls and towers. That was the first stone of Isabel I of Castile and Fernando II of Aragon of what would be modern Spain. On the night of January 1 to 2, 1492, 500 horsemen and 400 foot soldiers, with spy guns and lancers from Jaén, Úbeda and Baeza, under the command of the Major Commander of León, Gutierre de Cárdenas, took possession of the Alhambra. Three cannon shots at dawn warned the Santa Fe forces that the objective had been hit. At three in the afternoon, a sorrowful Boabdil greeted King Ferdinand of Aragon with respectful dignity and handed him the keys to the Alhambra so that he could take possession of it.

Preserve the Alhambra

Contrary to what might have been expected, the Catholic Monarchs had no interest in demolishing the Andalusian monumental complex. On the contrary, they fell in love with it and wanted to preserve it as well as possible so that it would last over time. The gardens full of fountains and waterfalls of the Generalife soon became Isabel’s favorite place, through which she liked to walk surrounded by those exotic palaces full of marble. It was on those walks where she decided that she did not want to be buried in Toledo, but in the Chapel of the Kings of the Granada cathedral built on the old great mosque.

Since then, the Alhambra has generated countless peculiar stories such as the bizarre property of the Generalife throughout the centuries and, above all, in the last century, when it was not even in Spanish hands, but Italian, with a lawsuit involved. of almost a hundred years to try to recover it for Spain in which several Kings of Spain were involved: Carlos IV, Fernando VII, Isabel II, Amadeo I, Alfonso XII and Alfonso XIII. Monarchs who, somehow, and just like the Catholic Monarchs, had to fight a second takeover of Granada, this time without blood, to recover that corner for the Spanish.

After the conquest in 1492, Isabel and Fernando turned the complex into a private estate managed by a kind of alcaidía that had the duty of managing and exploiting both the orchards and gardens of the Generalife, as well as “guarding its palace and land belonging to the kings, intended for recreation of the Royal Family”, in a position that would pass from father to son. The first two managed the impressive venue without a problem, but the third, Gil Vazquez RengifoCommander of Montiel, had no male offspring, only his daughter.

The Generalife, in the winter of 1926

The Generalife, in Italian hands

This was the first stumbling block in a family plot that would lead to the aforementioned litigation, after the daughter of Gil Vázquez married Pedro de Granada Venegas. This was the grandson and descendant of Sidi Yahya, Infante of Almería, governor of Baza and former vassal of the Catholic Monarchs during the conquest of Granada. A Muslim who had converted to Christianity together with his wife –hence the surnames that Pedro inherited–, thanks to which he was awarded by Isabel and Fernando with the titles of Major Constable, member of the Order of Knights of Santiago and Mr. of Campotejar.

In this accumulation of titles that Pedro de Granada Venegas inherited, together with his wedding with the daughter of Gil Vázquez and his role in the first Rebellion of the Moriscos in the Alpujarras between 1568 and 1571, he caused the successors of the Catholic Monarchs to grant him the precious property of the Generalife in perpetuity, which remained in the hands of his descendants for four hundred more years. This event marked the birth of one of the most important lineages of the European nobility after supporting Catholicism.

The Granada-Venegas family moved to Genoa in the 17th century after one of the descendants, Ana Venegas, married Juan Grimaldi, a nobleman linked to the Durazzo-Pallavicini house and the Landi family, resulting in a dynastic labyrinth difficult to find. explain. The important thing about this union is that, from 1672, the Generalife passed into the hands of this Italian family. Added to this is the fact that Mariana of Austria, Queen Regent during her minority, her son Charles II, once again granted “the perpetuity and ownership of the Royal Site with all the privileges that correspond to it.”

oblivion

The curious thing about this royal concession is that, after their final move to Italy, the Granada Venegas family never again set foot in Spain, Granada or the impressive Generalife gardens, which Muslims referred to in the past as “the gardens of paradise.” They remained closed, forgotten, suffering deterioration over the centuries, without being replanted or cultivated, with the only water from the rains, as if they no longer mattered to anyone, the people of Granada convinced that they would never recover the splendor of yesteryear. .

A century later, in 1805, Carlos IV filed a lawsuit to reinstate the Generalife and its annexed estates to his personal patrimony, with the sole objective of reselling it later to improve the Monarchy’s coffers. The acquaintance’Generalife lawsuit‘, therefore, it was actually started by his son Ferdinand VII in 1826, a decade after Napoleon’s troops had been expelled from Spain and three centuries after the conquest of Granada by the Catholic Monarchs.

If the matrimonial relations between the various Italian houses owned by the Generalife had already complicated everything a lot, the complicated and traumatic history of the 19th century in Spain did not help to solve the mess, with numerous civil wars, revolutions and regimes of all kinds. The Monarchy, expelled from power on several occasions, was in a weak position to demand anything. To this we must add the Spanish bureaucratic excess, which made it practically impossible to legally designate the Generalife as a property of the Spanish crown and not as a family inheritance of the Granada Venegas.

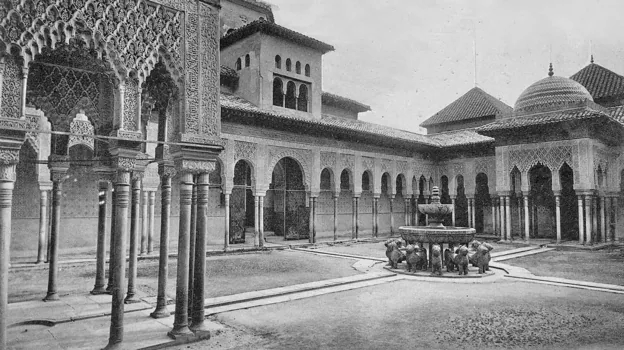

Court of the Lions of the Alhambra, in 1896

The struggle

It would be necessary to wait until the last years of the Restoration for the conflict to finally begin to see the light. In 1912, a resolution of the Granada judge Miguel Moreno Ortega it put the focus on the property of the Generalife, granting it to the State instead of to the Italian family. This did not give up and extended the process for another decade with a series of resources that are difficult to clarify after centuries of alleged ownership. In the end, other reasons weighed more, such as the difficulty of the Granada Venegas to maintain the land from abroad in an almost feudal system in the middle of the 20th century, the fact that they had not even visited it or that the last administrator of the Marquisate, Joseph Dane Morrionecommitted suicide in the Casa de los Tiros in 1918.

On August 23, 1921, the Royal Decree of August 23, 1921 was finally published, which produced the free transfer of the Generalife to the State by mutual agreement, as announced by ABC. The effective delivery was made in a public act in the Patio de la Acequia on October 2 of that same year. This included the aforementioned Casa de los Tiros, with the condition of converting it into “an institution for the promotion of intellectual or artistic culture.” From that moment until today, the complex will legally depend on the Board of Trustees of the Alhambra.