2024-10-31 14:07:00

+A-

“Oh, Russia, we know – Pushkin!”

The extraordinary fate of Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin. He had never been abroad, but he became the most famous Russian poet in the world. This happened when many were forced to leave Russia during the Revolution and Civil War of 1917. In a foreign land, Pushkin became for Russian refugees the homeland that they could take with them. His poems were translated, books were published in Russian and other languages, illustrations and decorations were created for the production of his stories, and memorable dates connected with the name of the poet were celebrated. An exhibition at the House of Russians Abroad, dedicated to the 225th anniversary of Alexander Pushkin, tells the story of the phenomenon of the Russian genius on the hill.

At the opening of the exhibition in the museum building of the House of Russians Abroad, venerable Pushkin scholars, museum workers, archivists and art historians gathered. The occasion is significant. Only the lazy ones did not make an exhibition about Pushkin, but here the “sun of Russian poetry” is told from an unusual perspective. The focus is on his posthumous life abroad, which has accumulated a unique phenomenon – “Russia abroad”. In the center of the exhibition is a huge library with translations of Pushkin’s works into different languages and publications published outside Russia or the USSR in other countries. Here is Dubrovsky, superbly illustrated by Evgeniy Lanceray. The artist did not emigrate, but lived and worked for many years in Tbilisi, far from his hometown and in moments of nostalgia he was saved by Pushkin, whose lyrics he adored. Next to the furniture, in scale, there is an installation in the form of a large chair, where everyone can take a photo in Pushkin’s Abroad.

“Queen of Spades” on silk

To the left of the giant bookcase are photographs of the graduates of Tsarskoye Selo (Alexandrovsky) High School, many of whom left, taking Pushkin’s Russia with them, spreading it throughout the world. The photo gallery is completed with photographs of Prince Mikhail Gagarin: here he is in Surin’s image of “The Queen of Spades” behind the scenes of the first production of the Parisian theater La Gaite Lurique in 1928, and here in Washington, where he also brought Pushkin’s word. To the right of the literary installation is a section with illustrations and decorative art objects, decorated with Pushkin subjects. Among the exhibitions, where everyone can be selected, there is a particularly unique edition on silk: “The Queen of Spades” in Brazilian. The playing cards depicted on the soft pages with the old countess in the protagonist role can be looked at endlessly. Next to it is a stunning drawing by Vasily Shukhaev for the same “Queen of Spades”, where the classic image of the Countess is covered by a corner card figured with the Queen of Spades. It was made in exile in Paris, with numerous repetitions and variations by other artists, the plot turned out to be so attractive.

Bookshop with the poet’s publications abroad

In the next section, a photo gallery attracts attention, where one after another photographs are replaced at Pushkin evenings and exhibitions abroad. Many of the writers who moved abroad became Pushkin scholars. The poems of the “Sun of Russian Poetry” were translated, for example, by Vladislav Khodasevich and Vladimir Nabokov. The poet’s legacy was published by Pushkin scholar Modest Hoffman, and Ariadna Tyrkova-Williams published a two-volume biographical work, “The Life of Pushkin,” which is presented in the exhibition in a French translation with corrections by ‘author. But Serge Lifar became Pushkin’s main follower, collector, curator and publisher in exile. The ballerina collected one of the most complete libraries of Russian literature in Europe. A special place in it was occupied by Pushkiniana, where the poet’s original letters to Natalya Goncharova were kept. Lifar published them in 1936 in Paris and after the war transferred the poet’s autographs to his homeland.

Exhibition curator Daria Zhmyleva at the exhibition

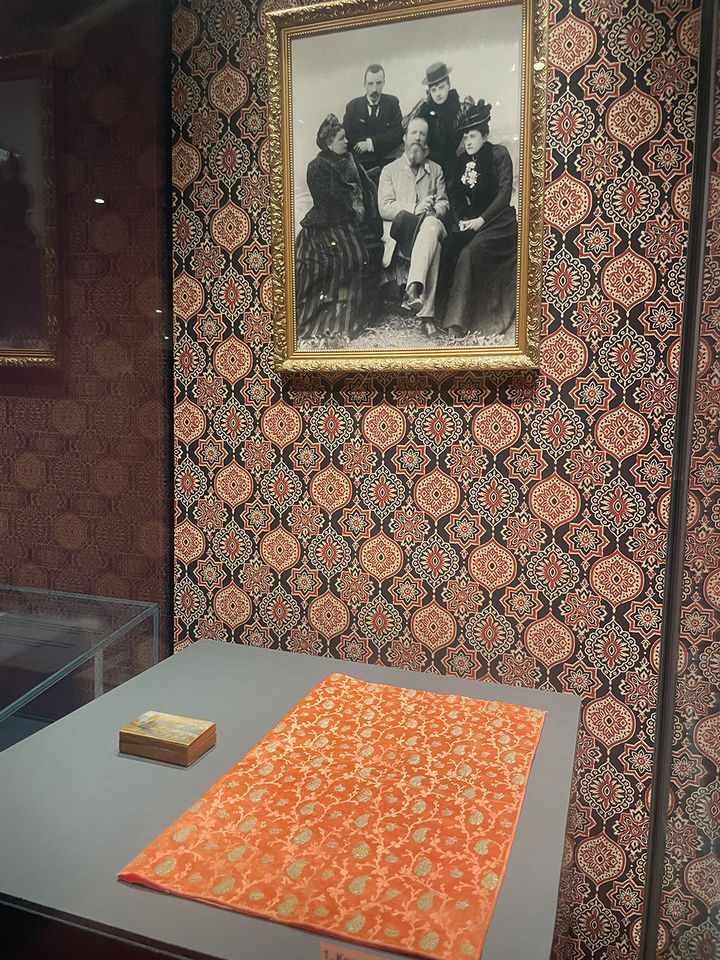

And on the centenary of Pushkin’s death, in 1937, Lifar initiated the creation of the Transatlantic Pushkin Committee and organized an exhibition in the Pleyel Hall in Paris, where he showed Pushkin’s Russia. The celebrations then took place in 42 states and 231 cities around the world. In addition to handwritten treasures, his collection also includes a curtain from an apartment on the Moika. Natalya Goncharova divided it into pieces between four children, and pieces of scarlet silk fabric traveled with them to different countries. The tone of this rag, presented in the exhibition in a separate display case, determined the color design of the entire exhibition. Subsequently, thanks to Lifar, the sections also returned to the Pushkin Museum Apartment on the Moika, which made the lion’s share of the pieces exhibited for the exhibition at the House of Russians Abroad.

Illustration by Vasily Shukhaev for “The Queen of Spades”

Next to a piece of fabric and photographs of Pushkin’s children, you can find another rarity – a sheet of yellowed paper with the recognizable handwriting of Marina Tsvetaeva – this is her translation into French of Lermontov’s poem “The Death of a poet”. Far from Russia, the longing Russian soul was saved by Pushkin. In 1937, Marina wrote “My Pushkin” – one of the most touching and sincere declarations of love to the poet, thanks to which he was rediscovered by many generations. 1937 was one of the most difficult years for Tsvetaeva in exile; he soon returned to the Land of the Soviets.

A piece of curtain from the poet’s apartment on the Moika

Pushkin abroad not only saved souls, but lives. Proof of this is the story of Peter Danzas, who emigrated with his family from revolutionary Russia in 1919 and lived in Paris, where he graduated from the Sorbonne. During the Nazi occupation of France he was mobilized and ended up on the Eastern Front as a translator. I was captured. When Russian counterintelligence learned that he was a descendant of Pushkin’s second, he was sentenced to execution in a camp. After his release, Peter Danzas worked as a journalist in the USSR and later returned to France. He almost didn’t live to see his centennial, dying in 2004.

Illustrations of Pushkin’s stories by Russian artists who found themselves in exile

Today, when you come to any country, be it Ethiopia, Brazil or France, if you have determined your Russian origin, you can hear: “Oh, Russia, we know – Pushkin!” The creator of the modern Russian language, who had never been abroad, spread throughout the world, where he became a living homeland for his compatriots and a symbol of Russian culture for foreigners.

General view of the exhibition with a portrait of Pushkin by Vasily Shukhaev in the centre. Work from 1937.

#foreign #Pushkin #shown #Russia #sun #Russian #poetry #illuminated #souls #emigrants

Org/QuantitativeValue”>

The impact of Alexander Pushkin’s work extended far beyond his lifetime, profoundly influencing Russian culture, literature, and the expatriate community. His poetry not only served as a connective tissue among those scattered across the globe, but also continued to inspire new generations of writers, artists, and translators who sought to preserve and honor his legacy.

This exhibition not only commemorates Pushkin’s profound influence but also symbolizes the enduring love and devotion his works inspired in those who admired him. Through various artifacts, letters, translations, and artworks on display, visitors can explore the indelible mark Pushkin left on the world, particularly during the tumultuous period of exile faced by many Russian intellectuals.

Among the highlights of the exhibition is the collection of Pushkiniana gathered by Serge Lifar, which shines a light on both the poet’s personal life and his broader cultural impact. The poignant connections between Pushkin’s works and the struggles of those who revered him can be felt throughout the exhibits, inviting reflection on the role of literary figures in the face of adversity.

As the exhibition concludes, attendees are reminded of the timelessness of Pushkin’s voice. His ability to resonate with feelings of love, loss, and longing remains as relevant today as it was in the 19th century. It serves as a reminder that the arts possess a unique power, capable of transcending borders and bridging the divides formed by time and circumstance.