The sun goes down and a group of burly men planted in the arena of the Colosseum shouts in unison the most famous phrase in the history of Rome: “Ave caesar, morituri salute you!”. They then fight, sword in hand, until only one remains. Does it ring a bell? This is the image that has been sold of gladiators, but it couldn’t be more wrong. They did not die, because it was very expensive to train them, they fought in the arena of the amphitheaters and, although it hurts us, they never pronounced that hackneyed maxim. But let’s be understanding. The ‘munus’, the gladiatorial combats, were the most popular of the Roman spectacles. And, as such, it is not uncommon that they have been mythologized in all the places that the legions trod. Among them, Spainwhere there is evidence of up to half a dozen fighters.

The story of these gladiators was not collected by the great classical authors and, therefore, has not been replicated in modern essays either. But their lives were not overlooked in the Hispania of the 1st century AD How many cheers would they get from the public, that the ancients left a record of their names and their deeds in a series of inscriptions on tombstones that were found in Córdoba in the decade 1950. According to experts, they would have fought in a series of exhibitions that were held in the first third of the century in the Betica province, at that time one of the richest in the Roman Empire. The same in which the third largest amphitheater in the world was built.

Gladiators in Hispania

One of the earliest recorded Hispanic heroes was Quintius Vettius Gracilis. The details of his life, revealed by the historian Antonio García y Bellido –born in 1903–, are not wasted, although they are scarce. The inscription found in Córdoba reports that he died in Nemausu when he was young, at the age of 25, and that he faced his enemies with the techniques of the Thracian people, located in the Balkan Peninsula. As the Doctor of History Alfonso Mañas explains in ‘Gladiators, the great spectacle of Rome‘, this type of gladiators were born in Rome in 80 BC, when Sulla took a group of prisoners of war from the Mithridatic army to the capital. When they stepped onto the sand, their teammates copied their techniques.

As a gladiator who fought in the Thracian manner, Vettius carried a ‘parma’ – a small rectangular or square shield – in his left hand and a ‘sica’ – a dagger with a curved or ‘L’-shaped blade – in his right. His defenses were the ‘ocreae’ – a decorated greave that covered his right leg and compensated for the small size of the shield – and a ‘manica’ or leather bracer on his right arm. Thus he won three laurel wreaths as a reward for his multiple victories. Although mystery remains, because we cannot know the exact number of battles in which he defeated his opponent. In the words of García and Bellido, the inscription on his tombstone was placed by his trainer, L. Sestius Latinus, and it is possible that he was an ‘autoratus’ or condemned.

Classic representation of the gladiators

The second Hispanic gladiator on record in Córdoba was called Emerald and hides a story even more concise than that of his colleague. We only know that he was from Cadiz, that he was probably a slave and that it was his wife who raised the tombstone in his honor. Little more. Neither the number of matches, nor the age at which he died, nor whether or not he won crowns as a prize are specified. What is indicated is that his specialty was ‘hoplomachus’. According to historian Pliny O’Brian, this type of gladiator would go out into the arena with a circular shield, full armor and a helmet. And, as offensive weapons, a spear and a short sword. They were the battle tanks of the time.

The third in discord was a gladiator whose inscription, damaged, could not be interpreted by García and Bellido. We only know of this anonymous hero that he also fought in the Thracian way. Little more. The Spanish expert also suspects that one of the words seen in the legend, ‘Sagitta…’, refers to ‘Sagittarius’. The ‘sagitari’ were a curious type of arena fighters, as they were equipped with bows and fought on horseback. Their equipment is believed to have consisted of a helmet, ‘balteus’ (a shoulder strap) and ‘lorica’ (an armor covering their torso). Next to this unknown warrior another Hispanic was buried, although not much is known about him either.

Hispanic and Vacceo

But neither Quintius Vettius Gracilis, nor Smaragdo. The Hispanic gladiator about whom we have more information was Marcus Ulpius Aracintus. Although his story navigates between palpable reality and assumption based on real events. García y Bellido, based on the inscription found in Córdoba about this character, argues that he was a vacceo –a people living in the Duero basin– who was recruited by the emperor Trajan to fight in one of his many auxiliary bodies. It is not strange, since our protagonist’s compatriots had a good military reputation for having stood up to the Roman legions of the Republican era.

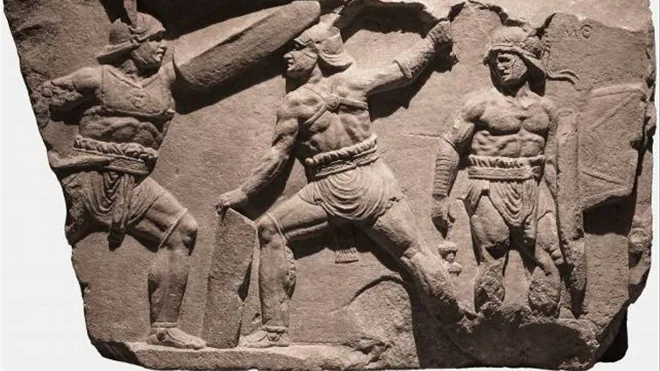

Relief of gladiators from the 1st century AD

However, it is difficult to trace it, since the classical authors do not refer to the existence of any empty auxiliary column. In the words of the Spanish historian, it is most likely that Aracintus went to nearby towns, those inhabited by the Arevaci and the Vetones, and, once there, he enlisted in the Roman legions. The inscription reveals that he fought eleven times and that, at the time of his death, he had risen to ‘primus palus’. Before, therefore, he had had to go through ‘quartus palus’ –title awarded for surviving the first fight–, ‘tertius palus’ and ‘secundus palus’. The last two, awarded for getting more and more victories.

«If he managed to win a certain number of combats, or showed great skill in some of his victories, the gladiator received the title of ‘primus palus’. This title would be granted by the college of ‘summae rudes’ that existed in each city with an amphitheater (in the Colosseum it was awarded by the college of ‘summae rudes’ in Rome). This implies that the members of these associations witnessed the combats (including the ‘summa rudis’ who refereed the combats, assisted by the ‘seconda rudis’), after which they decided if any of the combatants was worthy of receiving the title of ‘primus palus’”, he explains in his essay Mañas.

Schools… also in Hispania

Is it possible that there were more Hispanics on the arena of the amphitheaters? In the dossier ‘Hispanic participation in the Games of Olympia and the Roman Empire’, Juan Serrano Sayas confirms that the number was reduced because the Eternal City recruited a small number of soldiers on the Peninsula. However, he also specifies that an inscription found in Barcelona confirms that there was a school of gladiators in Hispania and that a certain man was in charge of it. L. Didius Marinus, ‘procurator of families through Gaul, Brittany, Spain, Germany and Raetia’. “Era, pues, una suerte de inspector general de aquellas tierras y provincias”, completa el experto.

Schools like the one in Barcelona were at the heart of the fighting; the place where novices learned through constant work by the ‘lanista’, the owner of the ‘ludus’ where gladiators were bought and trained. It all started with the arrival of the new recruits. The majority, slaves and volunteers with enough naso to put their physical integrity at stake in exchange for savoring the succulent honey of the glory that was acquired in that show. The professor emeritus of the University of California Robert C Knapp points this out in his conscientious work ‘The Forgotten of Rome’, in which he confirms that it was not strange that “free men” decided to be part of the gladiatorial family.

Borea, a Leonese known in the Roman Empire

Although he did not have a tombstone in Córdoba, Borea was also one of the most popular gladiators of the Roman Empire. Born in Asturian territory, in La Bañeza, to be more specific, he is known today for having received a thesarea, a distinction that was given to these fighters after being released for their exceptional career. Along with Spiculus, the favorite of Nero, he was one of the most famous fighters of the time. On the field he was a ‘provocator’, the first to go out into the ring.

Once in the arena of the ‘ludus’, those unfortunates received a blunt wooden sword and went through several tests in which their abilities were analyzed. At this first point, no special attention was paid to how they fought, but rather to whether or not they could put on a good show in the arena. Their speed, their physical abilities, their agility… and much more were studied. If he proved not to be too skilled in the art of fighting, the applicant was sent to the ‘gragarii’, large groups that fought together to make up for his clumsiness. Otherwise he was sent to learn the real trade. If he was more robust, to heavy weapons and, if he was lighter, to light weapons.

From then on, the capable soldier was known as a ‘shot’ or ‘novicius’ (a condition that he did not lose until he had overcome his first combat) and was trained by two characters. The first was the ‘doctor’, a retired gladiator who had excelled in the arena in a certain type of fighting and who instructed his pupils on a theoretical level due to his advanced age. The second was the ‘magister’, a younger arena veteran who had no problem taking on the recruits and showing them, first-hand, the best techniques to defeat his enemies. Next, the applicant fought (with blunt weapons, yes) against his companions to begin to tan. Caesar himself made reference to this structure in one of his many writings: «The lanista made the gladiators train by pulling».