Updated:

Save

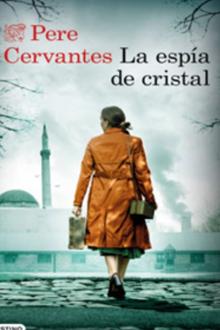

The deep voice and flat tone of the writer Pere Cervantes They echo through the phone. Although his weapons today are the pen and blank paper, there was another time, back in 1999, in which an automatic pistol rested on his waist. It hasn’t been long since this Catalan went to Kosovo as a United Nations Peace Observer. There he spent two years that marked him forever. “I started writing in 2012. I could have narrated the story then, but I needed time,” he tells ABC. He needed two decades for the wounds of what he lived there to heal. We have the result in our hands today,’the crystal spy‘ (Destiny); a black novel with police overtones that acts as a Time.news of one of the most atrocious conflicts of the last century.

And a book in which there is a lot of vital Time.news.

– When did you find out you were going to Kosovo?

A fax arrived at the judicial police in Barcelona in which they offered twenty places to go to the UN mission to Kosovo. They required English and five years of experience. I accepted. Then they put us through language, driving and shooting tests. We went with a certain idea, but, in the end, when we arrived, we dedicated ourselves to eradicating the weapons that were in the streets. You stopped a car and in the trunk there were two hidden rifles; we couldn’t arrest anyone because there was no room to incarcerate them; the vehicles were stolen from the east and did not have license plates; the street signs were ripped off… That level of madness made us wonder what we were doing there, living badly without electricity or running water, when we weren’t going to solve the problem.

– How was the situation when you arrived?

I arrived in August 1999. Officially two months had passed since the war in Kosovo had ended. The problem is that it was a hoax: although we were peace observers, we went armed with our pistol National Police. And I say little pistol because what was seen on the streets there were weapons of war, from Kalashnikovs to grenades… I came across a war scene, not a post-war one. There were no embers; there were still embers.

– What do you remember about Kosovo?

The noise of generators and helicopters, which was constant.

– What did you see on the ground?

I found all kinds of barbarities. Kosovar Albanian interpreters who are victims of rape, for example. That was the worst. There were 20,000 rapes in a war that killed 10,000 people. But it wasn’t the only thing. When we were on patrol, on the ground, we discovered mass graves on a daily basis. Some small, with a score of bodies, others more serious, with a hundred. Today, 23 years later, there are still 1,800 missing persons. It was something that changed my life.

– Why this ‘shock’?

For all. We brush against tragedy with anti-personnel mines. In January 2000, with 29 degrees below zero and on a road in full thaw, we saw how a van exploded with a family inside. Of our contingent, which was made up of about thirty policemen and civil guards, three did not return due to a plane crash due to a local error at the airport… We used to say that nothing works in the war and that, after the war, it works badly.

– Who are the good guys and the bad guys in this war?

It’s hard to tell without understanding the context. In 1989 Slobodan Milošević, President of Serbia, claimed that Kosovo was more Serb than Albanian. He took away the autonomy of Kosovar Albanians and made an apartheid. The worrying thing is that he carried out these measures in a territory where 80% of the citizens were Albanians. The population exploded and a kind of ETA was created, the KLA or Kosovo Liberation Army. Its members dedicated themselves to killing Serbian soldiers and policemen.

– What was happening, meanwhile, in nearby countries?

In 1991 the conflict of Bosnia; Yugoslavia he began to have the problem of radicalism alleging that the Muslims were conquering his territory; Slovenia became independent and Croatia y Bosnia everything flared up. Meanwhile, in Kosovo the situation and the war hardened by attacks. In 1999 barbarism was unleashed.

– Who were the bad guys from then on?

The Serbs. They committed atrocities, rapes, massacres, disappearances… I remember the images of exile, Kosovar Albanians crossing the border… But there was a third agent that we should not ignore. In March 1999, NATO decided to bomb Serbia, and it was done in a very brutal way. They launched 450 cruise missiles with a 15% error rate. If we do the math, about 60 fell who knows where. They also planted antipersonnel mines in Kosovo, hundreds of which are still buried. To make matters worse, when we arrived, the Kosovar Albanians took their revenge.

– Payback?

They took advantage of the fact that the Serbs were a minority. It was not a massive rematch, but moments of terror were suffered. I lived many of them. We gave protection to small villages of Serbs. We organized their security. Sometimes it went well, but other times it didn’t, and when you arrived, several families had already been killed. I think what I did the most was escort civilians when they went to buy food. I even transported milk in the UN police car, which we later distributed. And I’m not ashamed of it. We were going to give them an easy speech promising them security? We looked each other in the face and knew that it was impossible to fulfill it.

– An episode that particularly shocked you?

I remember that we were young and sometimes we shared time with the girls there. They could be between 19 and 25 years old. There was one thing that surprised us: many had false teeth. And we didn’t know why. One day they told us: when they were raped, the Serbs broke their teeth with the butt of the rifle so that the next person who came to their house would know that they had already been abused.

– Aren’t you surprised that such a conflict was experienced in that new Europe that yearned for peace?

The old continent, where we boast of having the best culture and of having illuminated works of art such as the Sistine Chapel, is where all these barbarities have taken place. And not in Auschwitz in 1942, but in the nineties, when the Barcelona Olympics had already passed.

– Was it worth going to Kosovo?

For me yes, it changed me; For the comrades who lost their lives, I would say no, but you never know. War is the worst thing that can happen to human beings, but for those who pass by, like me, it makes them a better person. I also do not know what the war journalists would answer. I have documented myself with books of Ramon Wolf, Gervasio Sanchez, Perez Reverte o Alfonso Armada and I have seen that they still carry many ghosts in their backpack. Normal, because what they saw was atrocious.

– Is this conflict over?

No, it’s still dormant. The war does not end when it is said on the news or on Wikipedia. Still continues. And you have to be careful because Ukraine could cause the Serbs to rise up, with the support of Russia, against the Kosovar Albanians.

– Was the conflict fomented so that the eastern countries would move away from Russia?

In the end, in the name of nationalism, the flag that was raised to justify their actions, the conflict broke out when the Serbs, backed by Russians, saw that the United States was going to establish the most important NATO military base on their territory. Something similar has happened with Ukraine, using post-truth – because Putin is making an overwhelming distortion of reality to justify his attack – a war has broken out that is still between the Russians and the Americans. In it, the poorest European countries have paid. Twenty years ago the world was less globalized and the Balkan war affected us less. Now the opposite happens.

– Has the fall of the USSR condemned the small countries of the East?

Yes. When I left Kosovo, a part of me said that I had lived through the last war in Europe. Call it naivety. When I found out what had happened in Ukraine I couldn’t believe it. Both will have the postwar in common. I did not see the current degree of destruction in Kosovo. Maybe some town. Now we have Mariupol or Kharkov ruined. The residue of that fall of the communist empire has condemned them. Russia, in return, has not fallen for its nuclear power and gas. If not, it would be a failed state.

– Why didn’t you write this book before?

I started my time as a novelist in 2012, and I could have done the history of Kosovo. But he hadn’t digested it. He was too emotionally involved and did not have the objectivity that was required. Nor did I intend to make an autobiographical work. I didn’t want to put the spotlight on me because I don’t give a shit about this conflict, I was just one more piece. And that, fortunately, I did not have to shoot and nobody shot me. He believed that I did not suffer post-traumatic stress, or maybe I only suffered it the first year after returning, but I read that two decades are necessary to overcome what is experienced in conflict. In my case it was nailed. From there I began to weave history and document myself. If you see the pile of books… I look like a madman from the Balkans.

– Does your novel follow the historical facts?

In the novel I forced myself to try to be as objective as possible. Reflect what happened. It is said that cruelty is the meeting point of humanity, and cruelty was the meeting point in the Balkans.

– Its two main characters are journalists…

Panco and Olga are two bitter people. In the end, a war reporter tries to portray the worst of the conflict so that what is happening is recorded and the madness stops. When they see that, despite their work and effort, everything goes on, or that these places are forgotten after the war, discomfort arises.

– Wouldn’t you have preferred the protagonist to be a policeman?

I was very tempted, but I didn’t want to reflect my experiences at that level. I created a character, Ricardo, who is a UN police officer and who lives the same as the reporters, also a spy, but the weight belongs to the journalists.

– Did you meet any spies there…?

Yes, several. They were between 30 and 50 years old. At first they manipulated you, they told you that they belonged to a Spanish NGO. But we caught them. When we asked them they told us yes, that they belonged to the CNI, but nothing more. I have created an espionage subplot because it bothered me so much to be a nerd. I was with the CNI, German agents, some of the Albanian intelligence services… We live in a small White House, and I didn’t know anything.

– What did your family tell you when you came back?

When I returned, my family asked me if the war was over. And no. I had finished my period there so as not to go crazy. Twenty years later it still hasn’t died down.

– Is it possible to forget?

We confuse the closing of wounds with oblivion. A rape victim whom I met, and with whom I have contact, confirmed to me that she is willing to close the wounds and forgive the new Serb generations. What she can’t do is forget. They forced fathers to rape their daughters, forced children to watch while their mothers were abused… How are you going to put that aside?

– A final note on the conflict or the novel?

Yes. The main idea of this novel is that those who cannot remember the past are doomed to repeat it. It is an anti-war book with every intention.

See them

comments