2024-07-14 03:59:36

“Men don’t turn to me anymore,” says Chantal. And blushes. She blushes like she hasn’t blushed in a long time. This unintentionally starts the crisis of a love relationship, which is told in Milan Kundera’s novel called Identity. Although one of the world’s most important novelists of the second half of the 20th century wrote it in French as early as 1996, it is being published in Czech for the first time only now, a year after his death.

The book, already published in the translation of Anna Karenina by Atlantis, begins in a seaside town in Normandy. Sailboats, waves and clouds on the horizon.

At the dam, where the sandy plain spreads out and people fly kites, we meet a pair of aging lovers: PR agency worker Chantal, who has a tragic past, and Jean-Marc. Their split will cause misunderstanding. To get rid of intrusive questions, Chantal regrets that men are losing interest in her. But she doesn’t say the sentence as lightly as she intended, and she blushes, which Jean-Marc misinterprets. Before long, Chantal starts receiving letters from a secret admirer.

From this point, a semi-serious, somewhat light-hearted prose unfolds, which already introduces bad dreams and which refers to Cyrano from Bergerac and Franz Kafka. Although he works with themes ranging from jealousy to voyeurism, Milan Kundera quickly moves from a lover’s crisis to an identity crisis. He thinks about what makes a person. To what extent does he behave differently in private than at work or in society, what face does he present to the world and which is the right one.

Several times he shows the fear of being mistaken for the physical appearance of a loved one, whom he considers incomparable. He considers whether the unique thing about a person is hidden in his face or other parts of the body. And because he is Kundera, he also writes about how those bodies fail under the gaze of others. To what extent are people captive not only to uncontrollable bodily movements, those blinking eyelids and inappropriate blushing, but also to crowd instincts, advertising slogans, in general various social pressures – for example having children. And where in all the big city hustle and bustle, in the anonymous crowds of never-ending masses of bodies, all reacting in the same way, all “condemned to food, to sex, to toilet paper”, as one character says here – where is there room for the free, nobody and nothing unmanipulated individual. Does he have a way out other than a desperate escape?

Style change

For someone who last read Milan Kundera’s novels The Joke or The Unbearable Lightness of Being, the first encounter with Identity can be slightly shocking. Instead of an extensive narrative, the book is only about a hundred pages long. The story is as condensed as possible, divided into dozens of short chapters and brief sentences. At other times, Kunder’s powerful narrator holds back. He follows sketched characters in carefully constructed situations that illustrate his reasoning and allow the reader to think about it.

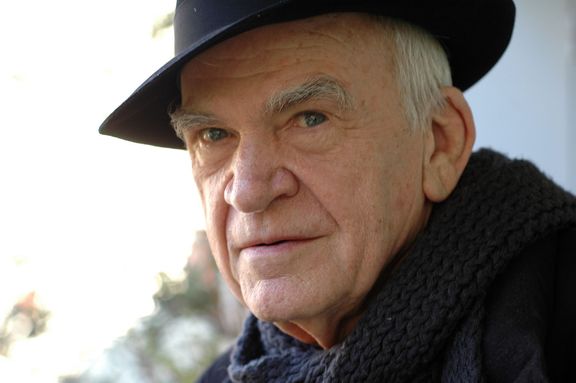

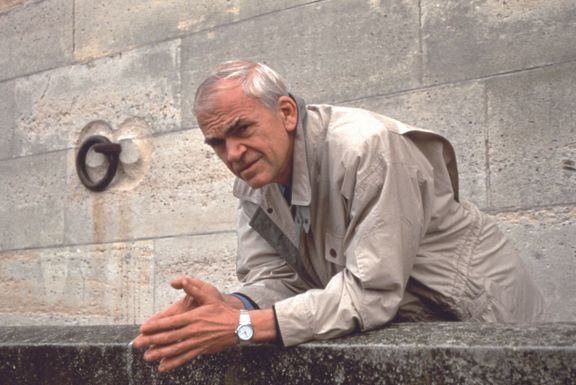

Milan Kundera lived in France since 1975. | Photo: ČTK / Gallimard

Probably the greatest contemporary Kunderov expert Jakub Česka, who published a book about the writer last year and has now written an afterword to Identity, explains this rather than a change in style as a gradual development. “I don’t think that the characters from older novels like The Unbearable Lightness of Being were significantly more fleshed out than the protagonists of Identity. Maybe they just worked on a larger surface. Also, the essayistic level was always present in his prose. In my opinion, the main difference is that in the 90s Milan Kundera started writing in French and these books of his are now much shorter, more condensed,” compares the literary scholar.

Kundera emigrated to France in 1975, where the following decade he achieved worldwide success with the bestseller The Unbearable Lightness of Being. In 1990, he completed the novel Immortality for the last time in Czech. And just after that, when he was a truly first-class literary star around the age of seventy, he wrote three short French prose works called Slowness, Identity and Nevédění in quick succession. He added the final Feast of Insignificance to them in the new millennium.

As before with Immortality, in Identity he leaves the Czech realities or history that he thought about before. “Identity is an intimate novel and the characters really seem almost removed from history. They are only anchored in time by a train ride under the English Channel,” notes Jakub Česka of the scene in which the protagonists travel to London through an undersea railway tunnel. It was commissioned in the mid-1990s.

Shortly thereafter, Miroslav Balaštík, the editor-in-chief of the Host publishing house and then head of the literary magazine of the same name, began to visit Milan Kundera. “We met for the first time in 1997,” he recalls, how he used to go to Touquet in the north of France every summer to see Kundera and his wife Věra, roughly the area where the story of Identity begins. “The Kunders had a summer apartment there, or rather two, where I spent four to five days with them and where we also agreed that Milan Kundera would translate some of his essays written in French for the magazine Host. He would then send them to Brno by fax,” describes Balaštík, how the author’s gradual return to Bohemia began.

Milan Kundera did not give interviews and did not like to be photographed. He wanted to disappear behind his work. | Photo: Catherine Helie © Éditions Gallimard

Stray echo

After 1968, the communist-banned writer could not publish in Czechoslovakia, so some of his most important novels, including The Unbearable Lightness of Being, were only known to readers for a long time from exile editions. After the Velvet Revolution, according to Milan Kundera, he did not want to overwhelm them, which is why he decided to introduce his books gradually, in the context of parallel translated essays explaining his thinking about the novel. Most of them were first printed in the magazine Host, then in thin volumes by the book Atlantis.

But the project stalled. The novelist, carefully guarding every word, had no time to edit his older Czech prose because he was writing new ones in French. And he didn’t have time to translate them into Czech, but at the same time he didn’t want to entrust that to anyone else. “Seeing yourself translated into your own language by a foreign hand seems like a perversion to me,” Kundera explained the unusual situation when, in the 1990s, his books were published in various world languages, including English, but not in Czech.

He apparently regretted it himself. “My novels are returning to Bohemia today, not as part of living Czech literature, but as a twenty-year stray echo left over from an unloved and irrevocably vanished era. Let no one suspect me of overestimating the role they can play in my former homeland today, ten, twenty, even thirty years after its creation,” he wrote at the time, for example, in the afterword to Immortality.

Because he rarely returned to the Czech Republic after the coup and always incognito, some accused him of resenting his native land. The consequence was sometimes criticism in the press, sometimes on purpose. For example, in the 1990s, the Votobia publishing house published an interview with Kundera as a book without the author’s consent, which it then had to withdraw from circulation. In 2006, a pirated translation of the novel Identity appeared on the Internet. The agency representing Kundera, Dilia, responded by filing a lawsuit. The unknown perpetrator could not be found.

Only in the last years of his life did Milan Kundera realize that he would not have the strength to translate his French books into Czech, and hired the respected translator Anna Kareninová. With her, he still had time to consult Slavnost bezzáznosti and Nevědění, published in Czech in 2020 and 2021. Exactly one year ago, the writer died, he was 94 years old.

The identity is now the first that the translator prepared without him. “I think that even a reader thoroughly familiar with Milan Kundera’s writing would not recognize the difference. The translation of Identity seems just as authentic as the novels he wrote in Czech,” praises the literary scholar Češka.

Kareninová studied the author’s style thoroughly and reconstructs it from the occasional use of transitions to the occasional choice of unexpected words – in the Celebration of Meaninglessness, it was the navel instead of the navel when describing the female body, in Ignorance and Identity, a snot is heard instead of a snot. The Brno native had previously used both terms in texts written in Czech.

After 1989, Milan Kundera only traveled to the Czech Republic incognito. | Photo: Gallimard

What comes out and what is left

Now only Slowness from 1994 remains to be translated from Kunder’s prose. Even then, Czech readers will still miss the quartet of essays The Art of the Novel, Betrayed Testaments, Opona and Setkání, compared to the French. “They also deserve to be published as a whole. The essays that he translated for Host and then published as books in thematically conceived notebooks had their own logic, but in retrospect it caused a bit of confusion in Kunder’s work,” states Miroslav Balaštík.

Literary scholar Jakub Česka would also welcome a book edition of the essays. “Perhaps I particularly like one of the Betrayed Testaments, which relates to Franz Kafka and whose title is often translated as Journeys in the Mist,” mentions the text, which reads several tens of pages and in which the writer also recalls an experience from the time of communism or returning to the homeland after in 1989. There is no Czech translation yet.

The Milan Kundera Library has been operating in Brno since last year, where, according to the ČTK agency, it was possible to transfer almost a ton of books from the writer’s apartment in Paris. They are now being processed by researchers led by Jindra Pavelková. And soon readers will meet the author again, at least indirectly. Already at the end of next month, Miroslav Balaštík will publish Kunder’s new biography, written by the renowned French novelist Florence Noiville, in the Host publishing house.

“It is not a scientific monograph, but rather a fictionalized personal report taking into account the fact that the author was friends with Kundera for many years and visited him in the last months of his life,” says Balaštík.

According to him, the volume is accompanied by photographs from the writer’s apartment and places associated with it. In addition to short interviews with Kundera, the memories and comments of his wife Věra and several Czech friends, for example the composer Miloš Štědroná, are important in the publication. “Of the books about Milan Kunder published so far, I find this one the most literary and the most readable,” concludes Miroslav Balaštík.

Milan Kundera: Identity

(Translated by Anna Karenina)

Atlantis 2024 publishing house, 136 pages, 330 crowns.