Low birth rate – Decrease in number of aspirants due to dereligionization

Accepting a foreign monk as a superior… Theological colleges are reducing the number of students and even closing them down.

There is no good way to increase the number of monks… “If this continues, there will be more empty temples and empty cathedrals.”

The head monk of a temple in the Gangwon area is seriously considering accepting a foreign monk as his superior (disciple who continues the master’s line). While I was unable to find a theravada due to the rapid decline in the number of monks, I heard from an acquaintance, “There is a Sri Lankan monk who wants to become a monk again in Korea.” He said,“The number of monks has decreased so much,and we are worried as no more people want to come to a small temple like ours.”

The religious world is shaking from the bottom as religious figures such as monks and priests continue to decline due to low birth rates and dereligionization. Beyond studying abroad, foreign monks are being accepted as therapists, and theological colleges are being abolished. Some predict that “if this trend continues, the import of foreign abbots and priests, as well as empty temples and cathedrals, may accelerate.”

A monk in the Jeollanam-do region received a Buddhist monk from Nepal as his therapist a few years ago. Foreign monks usually come to Korea to study, but they have returned to Korea to become monks. The monk who accepted the Nepali monk said, “I accepted it because of a connection, and contrary to my concerns, he speaks Korean well and has adapted well, so I am satisfied.”

According to the Buddhist community, it is indeed known that in small religious orders where the shortage of monks is more serious, the number of cases of receiving Southeast asian monks who have rejoined the Korean Buddhist community as therapists is gradually increasing. As a result, in some cases, the difficulty in recruiting monks is causing side effects, leading to employment fraud. In areas with relatively arduous economic conditions, such as sri Lanka, there is a situation where brokers turn ordinary people into ‘disguised monks’, bring them into the country, and then disappear. Unlike work visas, religious visas can be issued only with an invitation letter from a temple or monk, which is exploited.

For this reason, the General Affairs Office of the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism sent an official letter to temples across the country in July this year requesting management and supervision to prevent foreign monks from leaving and held a related meeting. The General Affairs Office said, “foreign monks from other religious orders often disappear after entering the country due to reasons such as a decrease in the number of monks, so as a precautionary measure, we held a meeting with the head monks of about 20 temples that invited foreign monks.”

Pusan Catholic University’s College of Theology, which trains priests, was abolished from the 2019 school year due to a lack of new students. Among the seminarians, those from the Diocese of Busan were sent to Daegu Catholic University, and those from the Diocese of Masan were sent to Gwangju Catholic University. According to ‘Korean Catholic Church Statistics 2023’, the number of students entering Catholic theological schools nationwide decreased from 143 in 2013 and 130 in 2018 to 81 last year. Catholic universities generally have a quota of

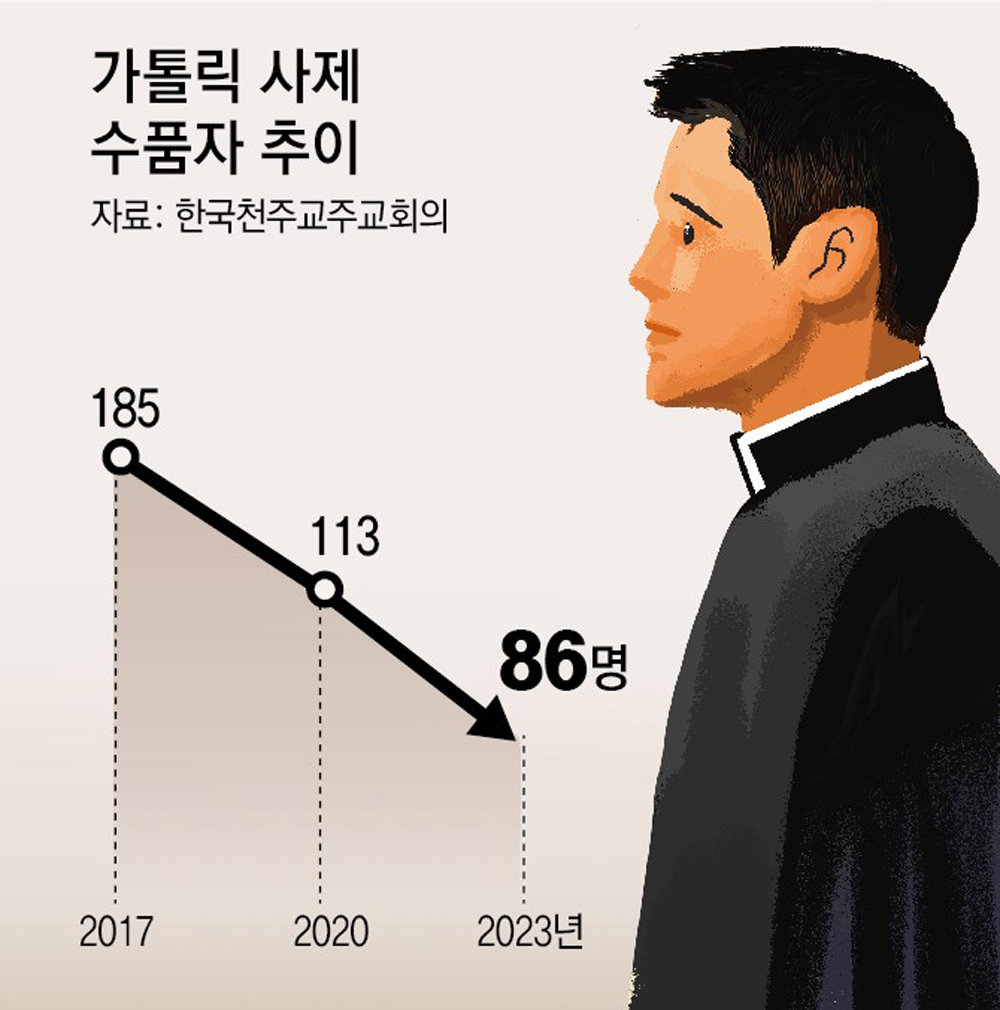

The number of priests receiving ordination each year fell from 185 in 2017 to 113 in 2020 and 86 last year. Since it takes about 10 years, including military service, to become a priest after entering school, there is not yet a shortage of priests, but some predict that if this situation continues, it will only be a matter of time before schools are merged and churches are integrated.

Though, some say that it is indeed difficult to find a sharp solution. The Jogye order, whose number of monks has plummeted from its peak of 532 in 1999 to 287 in 2010, 131 in 2020, and 61 in 2022, is implementing the ‘retired monk system’, which expands the age of retirement for monks from under 50 to 65, and ‘youth monks’ Due to the introduction of support measures such as the ‘short-term monastic order system’, the number of monks became monks last year was somewhat small (84). Although it has increased, the internal trend is that it is not enough to stop the trend.

An official of the Jogye Order said,“There are 25 parishes across the country,but if the number of monks last year was 84,it means that we can only assign 2 to 4 people to each parish.” He added, “But we are worried because there is no way to suddenly increase the number of monks.” An official from the Catholic Central council of Korea also said, “There has been no full-scale discussion yet, but there is talk that ‘if this trend continues for 10 years, we may begin to bring priests from Catholic countries such as the Philippines.’”

Reporter Lee Jin-gu [email protected]

- I’m sad

- 0dog

- I’m angry

- 0dog

Hot news now

- I’m angry

- 0dog

What are the potential cultural impacts of accepting foreign monks in Korean temples?

Interview: The Future of Monastic Life in Korea

Editor of Time.news (ET): Welcome! Today, we have an insightful discussion lined up with dr. Han Ji-soo,an expert in religious studies and the sociocultural implications of declining birth rates on monastic life in Korea.Thank you for joining us, Dr. Han.

Dr. Han Ji-soo (HJ): Thank you for having me. It’s a pleasure to be here.

ET: Let’s dive right in. the recent article highlights a concerning trend regarding the low birth rate and dereligionization, notably impacting the number of monks in Korea. Can you elaborate on what this means for the religious community?

HJ: Certainly. The decline in the number of monks is alarming, reflecting broader cultural shifts. With low birth rates, fewer individuals are entering monastic life, leading to a dwindling pool of spiritual leaders. This is exacerbated by dereligionization, where younger generations are increasingly distancing themselves from conventional religious practices.

ET: I see! There was a mention of temples considering accepting foreign monks due to this shortage. What are the implications of bringing in foreign monks as superiors or therapists, both for the temples and the Korean Buddhist community?

HJ: This is a complex issue. On one hand, accepting foreign monks can bridge the gap in leadership and provide fresh perspectives within the community. However, it poses risks of cultural disconnect, especially when integrating diverse practices into traditional Korean Buddhism. Moreover, if the trend of recruiting foreign monks continues, it could lead to a dilution of indigenous practices.

ET: Interesting! The article touches on some worrying side effects, such as employment fraud related to foreign monks. What do you think about this troubling trend, and how does it reflect the broader community challenges?

HJ: Employment fraud is indeed a notable concern. The exploitation of foreign monks, particularly from economically disadvantaged regions, highlights the desperation within some temples. It reflects not only the recruitment challenges faced by these institutions but also the broader issues of economic disparity and the need for tighter regulations to safeguard all involved.

ET: The article mentions that the Jogye Order is implementing measures to address the declining number of monks, such as extending the retirement age. Are these measures enough to curb the downward trend?

HJ: While these measures are a step in the right direction, they may not be sufficient in isolation. The decline in interest among younger generations is tied to societal changes rather than just institutional policies. Ultimately, revitalizing interest in monastic life will require more profound cultural shifts and engagement with younger audiences, perhaps reimagining how spirituality is presented in modern contexts.

ET: You mentioned engagement with younger audiences. What role do you see educational institutions playing in this renewal?

HJ: Educational institutions can play a pivotal role by modernizing the curriculum and making it more accessible. As a notable example, theology schools should address contemporary issues and incorporate diverse views to attract younger students. The declining enrollments in theological colleges, as seen with Pusan Catholic University, indicate that there’s a crucial need for reform to make these institutions more relevant today.

ET: Speaking of relevance, what are some strategies that could be employed to enhance the appeal of monastic life to the younger generation?

HJ: Engaging in social issues, such as environmental concerns and social justice, could attract youth to monastic life by connecting spiritual practices with real-world challenges. Additionally, using social media and modern communication tools to share stories and experiences of monastic life could also help to paint a more relatable image.

ET: Dr. Han, if current trends continue, what do you predict for the future of monastic life and religious institutions in korea?

HJ: If proactive measures are not taken, we may see more empty temples and diminished spiritual guidance for communities. It could lead to greater integration of foreign monks, but the essence of Korean Buddhism might fade. Innovation, adaptability, and a focus on community engagement will be critical for the survival and relevance of monastic life in Korea.

ET: thank you, Dr. Han, for your insightful perspectives on such a pressing issue. we appreciate your time and expertise today.

HJ: thank you! It’s been a pleasure discussing these critical topics with you.