«I started my professional life at FC Barcelona, at a time when the political environment imprisoned and governed all activities. In Catalonia he was heavily influenced by separatist ambition. My profoundly Spanish sentiments, of unity and greatness of the country, made me leave that environment that suffocated me and go to the Spanish Sports Club, where my affinity with its patriotic sentiments was evident”, wrote Ricardo Zamora in August 1940.

It was one of the arguments used by the Catalan goalkeeper in the appeal filed with the Spanish Football Federation (FEF), to try to get the dictatorship to lift a three-year penalty for not traveling to the Franco zone during the Civil War. Six pages full of details about his life that had not seen the light until today. ABC has obtained them exclusively, along with other documents, from the descendants of a high-ranking official of the Franco regime who tried to intercede for the star at the time, after she spent several months in a Republican prison and fled after the exile bombs.

«From that departure of mine from Barcelona [en 1922] –Zamora continued in the next paragraph– the press echoed the political meaning of my march. A sense that not only did I not try to avoid, but was reflected in a letter that was published by all the press, in one of which I said: ‘I am leaving after a three-year excursion abroad, alluding to Barcelona, to the land of my loves, in reference to the Spanish, identified with my idea of the homeland’». To make it clear, he underlined the expression “for the foreigner”, which he included in a section that the footballer called “Antecedents of my public performance before the National Movement.”

However, in that atmosphere of repression that followed Franco’s victory, the goalkeeper’s words should not be interpreted hastily, because his ideology had always been unknown. Was he left or right? Was he being honest or was he simply trying to survive and save his career, like so many other Spaniards at that time? “The sanction imposed is so serious that, apart from the pain that being separated from the only activity that gives me economic means to live represents, it morally supposes a more intense pain, since, always vigilant of the principles of the Glorious National Uprising, in the The moment in which these are established as the guidelines of the new state, is when my harsh postponement arrives, ”he insisted.

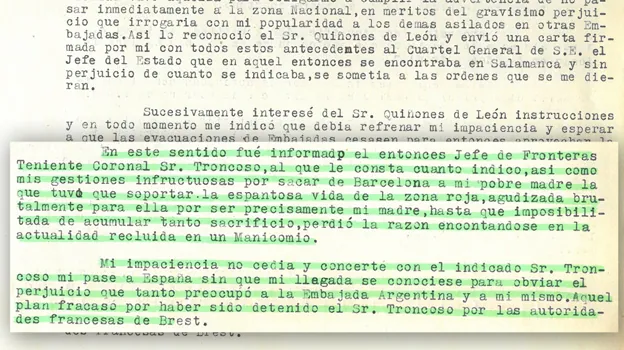

Extract from the appeal that Ricardo Zamora presented to the FEF in 1940, where he refers to his past at FC Barcelona and the reasons why he decided to sign for the Spanish

Zamora, against Nazism

The truth is that in the months prior to the outbreak of the war, Zamora fueled the confusion regarding his political ideas. And, being the equivalent of Messi or Cristiano Ronaldo of the time, it was impossible for the press and the radio not to talk about him on a daily basis. For many he was a monarchist and a Catholic because he wrote a column in the conservative newspaper ‘Ya’. In February 1936, however, when the Germany players gave the Nazi salute at the start of a match against Spain at the Estadio de Montjuic, he raised his fist defiantly at the sound of the Republican anthem.

On June 21, on the other hand, during the celebration in Valencia of the Republic Cup that he won against Barcelona –the same day that he said goodbye to his career as a player with that impressive save for Josep Escolà–, Zamora concluded his speech as captain with a “Long live Valencia, Madrid and Spain”. At that moment, a journalist yelled at him “and long live the Republic too!”, but the goalkeeper did not join. He remained impassive. It is as if he were not attached to any ideology, or to all of them at the same time, in a lack of definition that brought him problems twice, since he was persecuted and imprisoned by both sides during the war, before they imposed the sanction that threatened his coaching career.

In principle, Zamora had nothing to fear in July 1936. Six years earlier, Real Madrid had paid 150,000 pesetas for his signing, an exorbitant figure that took years to be surpassed. Wherever he went he was treated like a star by all Spaniards, regardless of the party they voted for. In July 1936, at the age of 35, he was still the great hero of the silver medal at the 1920 Antwerp Olympic Games. However, he made a mistake. Upon returning from the final, the climate of insecurity and violence was so great that his teammates took advantage of the club’s permission to leave Madrid, but Zamora decided to stay, trying to go unnoticed in the middle of the powder keg.

Paragraph of the appeal in which Zamora expressed his concern for his mother’s health

You take them out of Paracuellos

Clashes in the streets led to the assassination of Socialist Lieutenant José Castillo and Conservative Deputy José Calvo Sotelo on July 12 and 13, respectively. When the war broke out on the 18th, Zamora began to be harassed by the Republicans and decided to take refuge in the houses of friends, but was arrested by a group of militiamen. Years later, his son remembered those days: «They came home and took cups and medals. Even your car. Once in the Modelo prison, a militiaman recited several names every day that they took away and did not return. My father was quoted several times and he got tremendous scares. What happened is that the commissioners in charge of the list included it just to get to know it ».

This is how the Madrid captain survived the sacking of prisoners that, between November and December, caused thousands of deaths in Paracuellos. Several historians have inquired about the identity of the militiaman who saved him. Ramón Gómez de la Serna published a Time.news in the Argentine newspaper ‘La Nación’ in which he mentioned the poet Pedro Luis Gálvez: «Gálvez’s appearance in prison is a blast of fright. He addresses the prisoners in a boisterous attitude and bombastic tone. He plays with guns like a juggler. He every once in a while he saves a man. One morning he showed up at La Modelo and went out onto a patio balcony with a prisoner on his arm and shouted: ‘Here is Zamora, the great international player. He is my friend and many times he fed me. He is imprisoned here and it is an injustice. Let no one touch a hair. I forbid it’. Then he kissed him and hugged him while he shouted ‘Zamora Zamora!’, Before the astonished prisoners ».

In mid-November he was released, perhaps helped by the friendly match between the Valencia and Catalonia teams to demand his release and the letters from foreign players that arrived at FIFA headquarters. Fearing that he would be assassinated, he took refuge with his family in the Argentine embassy. «Ricardo considered leaving, thinking that they would respect him because of his popularity, but we dissuaded him. They would have killed him for sure,” said one of the refugees who accompanied the Zamora family on the delegation later.

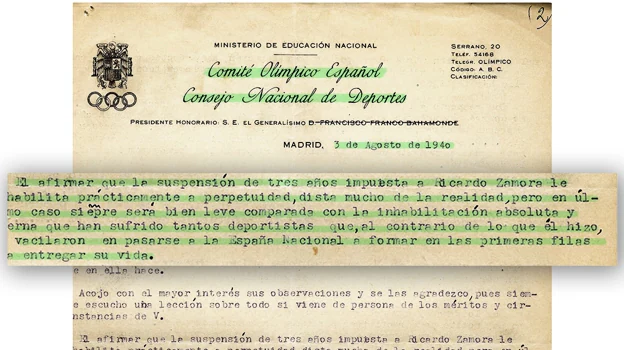

Private letter from General Moscardó, in which he explains the reasons why the sanction against Zamora has not been withdrawn

The departure from Spain

In February 1937, the goalkeeper was escorted to Alicante by a very large crew of motorists from the Assault Guard, and from there he embarked for Marseille, to later go by road to Paris and Nice. He was in this last city until December 1938, extending his career as a player two more seasons in the city club. There he met José Samitier, his teammate at Madrid and Barcelona. At the beginning of his stay, the news of his assassination by the Republicans circulated. The French newspaper L’Auto came to report it: «The news has reached us as abrupt as dry: Ricardo Zamora is no longer here. He was probably the best goalkeeper of the last ten years. He earned his reputation on the fields around the world and was still the best goalkeeper in Spain, despite being over thirty ». In Valladolid, a funeral mass was even celebrated in his honor and Queipo de Llano condemned his death in one of his fierce radio speeches.

When the Francoist authorities learned that Zamora was in Nice, they invited him to return, but in his appeal he explained why he did not: “The Embassy attache, Edgardo Perez QuesadaHe warned us that his government had given the word to the red government that the evacuees would not go into the national zone. I didn’t give it any importance, given my desire to move to the Spanish zone clean of that rotten and criminal environment. However, Mr. Quesada warned me in particular to be careful, signing a document, because given my popularity, if my passage to the national zone became known, it would harm other Spaniards who were anxiously awaiting their release.

Zamora finally returned to Spain in August 1938. A law from the first Franco government in Burgos established that those fleeing from the Republic who wanted to enter the Franco zone only had two months. Franco did not like that he had taken more than a year. He also did not forget the tribute paid to him, in 1934, by the Republican president Niceto Alcalá-Zamora and the footballer’s statements in Paris, published by the newspaper ‘Sport’ on April 2, 1937: «I will never go to Burgos. Say in Spain that I am not a fascist ». He was arrested after playing a charity match in San Sebastián and imprisoned this time by the opposing side, but released a few days later to avoid an international controversy. Then came the sanction.

In the old folder that contains the appeal, it appears written in pencil: “Summer of 1940. Moscardó refused to lift the sanction.” This was the case, at least, initially, as confirmed by an apology telegram that he sent to Zamora for not having been able to help him and a letter from General Moscardó, head of the Military House of the Head of State, in which he explains his reasons. : «Affirming that the suspension disables you in perpetuity is far from reality. In the latter case, it is very slight compared to the absolute and eternal disqualification that so many athletes have suffered who, on the contrary, did not hesitate to go to national Spain and give their lives at the front.

Read more history reports here.