The Unexpected Rise of a 21st-Century Guide to Tyranny

A history professor’s slim volume, On Tyranny, has become a surprising bestseller, fueled by TikTok and anxieties about democratic backsliding—but its prescriptions for resistance clash with the very platforms driving its success.

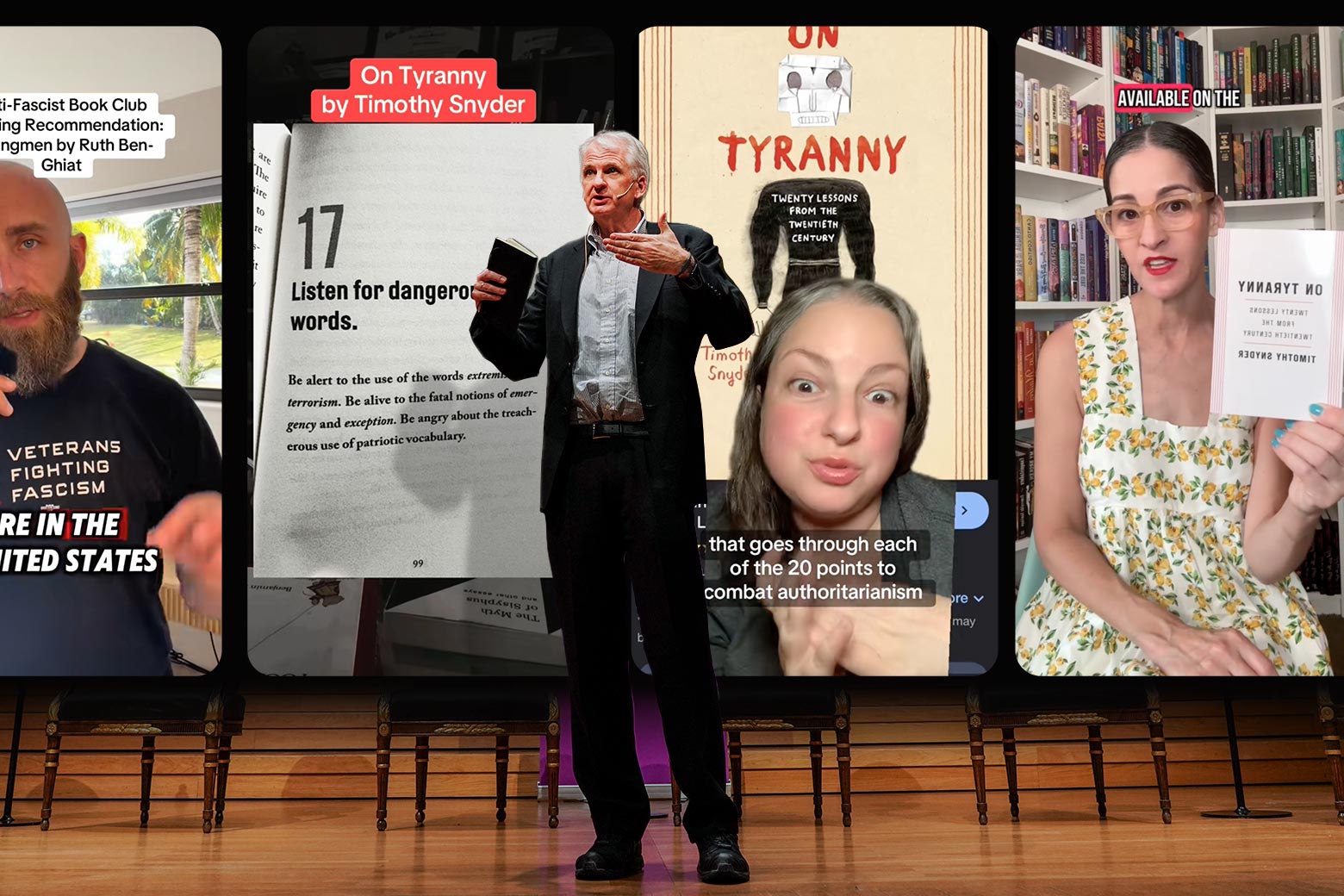

A peculiar phenomenon is unfolding in the world of books: every time I succumb to the brain-rotting allure of TikTok, it seems I see the same figure—a wiry, middle-aged man with a grizzled gray beard and knit beanie, standing in a vaguely rural setting. He’s often discussing On Tyranny, a 2017 book by historian Timothy Snyder. In one video, he holds up the book, insisting that if it were “required reading in every middle school across the country, we wouldn’t be in the mess we’re in now.”

That man in the beanie is far from alone. Publishers Weekly reported last month that On Tyranny is a top seller at numerous independent bookstores, coinciding with a surge in sales for titles addressing autocracy. TikTok and other social media platforms are awash with posts about Snyder’s work, which, as its subtitle explains, offers 20 lessons from the 20th century on how tyrannical governments take hold in democracies and what citizens can do to stop them. The book’s concise, bullet-point format and short chapters lend themselves perfectly to shareable snippets of exhortation; lesson No. 1, “Do not obey in advance,” urging resistance to appeasement, is a particular favorite. Some TikTok users even temporarily cede control of their accounts to narrate the entire book, one chapter per video.

On Tyranny’s success isn’t unprecedented. Bookstores have long displayed impulse-buy books near cash registers, a mix of serious and frivolous titles—in 1982, Jonathan Schell’s The Fate of the Earth and Thin Thighs in 30 Days were the two biggest point-of-sale bestsellers. However, traditional retail merchandising isn’t the driving force behind On Tyranny’s current popularity. It’s the internet—primarily testimonials on TikTok (and links to the TikTok store), alongside memes shared on Facebook and other platforms—that has propelled Snyder’s book to 1.4 million copies sold, with 250,000 copies sold this year alone. While social media is crucial for most bestsellers, the “memeification” of On Tyranny is particularly ironic, given that Snyder attributes our drift toward authoritarianism, in part, to the internet itself.

The book’s brevity and simplified “lessons,” presented in the popular listicle format, might irk some historians. Those familiar with 20th-century history will likely recognize the patterns of European authoritarianism Snyder illustrates, drawing examples from the Soviet Union, Nazi Germany, and Czechoslovakia. Yet, works like On Tyranny serve a purpose. Published a year into the first Trump administration, it provided a readily accessible framework for citizens unfamiliar with that history to assess the regime’s actions for signs of a similar slide into autocracy. As Snyder himself—whose more academic work, The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999, has not achieved comparable sales—surely recognizes, not everyone has the time or inclination to engage with lengthy works of political theory or history. Many TikTok users have described On Tyranny as a “quick read,” unburdened by excessive dates and details. It’s a kind of “Hannah Arendt for Dummies,” but that’s not an insult—sometimes, readers simply need a basic explanation of complex concepts.

Furthermore, the core concepts within On Tyranny are sound. Snyder avoids partisan squabbles by highlighting both fascist and communist totalitarianism as examples of tyranny. The social pressure to conform, reluctance to resist even minor penalties, the degradation of language and truth, and the expansion of surveillance—all are factors that have historically signaled increasing authoritarianism. Many recognize this process as a gradual slide, not a sudden revolution, and understand that past generations complacently overlooked these changes. On Tyranny can help readers avoid repeating that mistake.

However, the book’s recommended remedies may perplex its online fanbase, particularly younger readers. On Tyranny urges readers to avoid getting their news from the internet and to “subsidize investigative journalism by subscribing to print media.” Snyder implies that truth is inaccessible online, writing, “Staring at screens is perhaps unavoidable, but the two-dimensional world makes little sense unless we can draw upon a mental armory that we have developed somewhere else.” He argues that learning from screens draws us into “the logic of spectacle,” making us susceptible to manipulation by any backlit content.

While acknowledging that “protest can be organized through social media,” Snyder maintains that “nothing is real that does not end on the streets.” He believes that without tangible consequences for actions in the physical world, nothing will change, and that citizens must engage with those they disagree with to defeat creeping authoritarianism.

Snyder’s assessment is largely correct, though his notion that information conveyed via a screen is inherently less reliable than print feels like a form of nostalgia. It’s true that conflating online life with reality can lead to the mistaken belief that reality can be curated like a social media feed, and that blocking dissenting voices will erase them. The internet’s echo chambers do foster extremism and paranoia. As Snyder succinctly puts it, “There is a conspiracy that you can find online: It is the one to keep you online, looking for conspiracies.” And privacy, readily surrendered by many, is anathema to authoritarianism.

But telling 21st-century readers to treat “email as skywriting” and to use the internet less feels out of touch. Effective 20th-century resistance movements, like the Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia, resisted in the streets and through samizdat publications—they didn’t have the internet. Many now believe their voices reach further online than through street protests, and see little difference between the two. After all, they might argue, their online posts are what are spreading the word about On Tyranny.

Only a few years ago, Snyder might have faced criticism online for this perspective, when younger audiences readily challenged their elders for “not understanding the internet.” The relative silence on this point now suggests a growing understanding of the internet’s complexities. The current political climate often manifests as the worst aspects of online culture—bigotry, unfounded confidence, trolling, and rage. No one is immune. Although On Tyranny was initially published in response to Trumpism and has been updated to reflect recent events, Snyder avoids naming the former president, referring to him only as “the candidate” or “an American president”—a choice that, while perhaps intended as high-mindedness, comes across as a book-length subtweet.

The internet, alas, is here to stay, and it’s unlikely the New York Times is seeing a surge in $780-a-year print subscriptions from On Tyranny’s TikTok admirers. Taking to the streets remains a powerful demonstration of public demand for change, but a viable online response is essential in the fight against authoritarianism—one that defends democratic institutions, upholds the rule of law, and articulates a compelling alternative for the digital age.

That comprehensive response is absent from On Tyranny, despite its other virtues. Perhaps that’s why, earlier this year, Snyder joined two Yale colleagues—including his wife—in accepting positions at the University of Toronto. Snyder has stated that he left primarily to support his wife’s protest against the Trump administration’s attacks on civil liberties, and considers her motives “reasonable.” However, squaring this with Lessons 19 and 20 from On Tyranny—”Be a patriot” and “Be as courageous as you can”—raises questions. Is weighing in on the American crisis from Canada a more immediate engagement than making TikTok videos? “Don’t be a bystander,” urges a promotional e-card for On Tyranny on Snyder’s website. But whether one is standing by or standing up depends on where one believes the fight lies.