Cells’ ‘Dark Mode’ Defense Against Viruses Unveiled in New Study

A groundbreaking study published in June 2025 sheds light on a previously misunderstood defense mechanism employed by human cells to combat viral infections, offering potential avenues for developing next-generation antiviral therapies.

Cells have evolved ingenious ways to defend themselves from viral attack, and researchers at The Wertheim UF Scripps Institute have uncovered one of thier sneakier strategies. If a home is threatened by an intruder, a natural response is to hide and seek help. Cells, it turns out, can do something similar – temporarily shutting down their metabolic processes to evade viral control.

How cells ‘Go Dark’ to Fight Infection

The research, detailed in the journal Genes & Development, focuses on the cellular response to infection with West Nile virus. According to a lead researcher, “One of the questions we wanted to address in this study was, how do cells make the decision to degrade all of their own RNA?” The answer, it appears, is far more complex than previously understood.

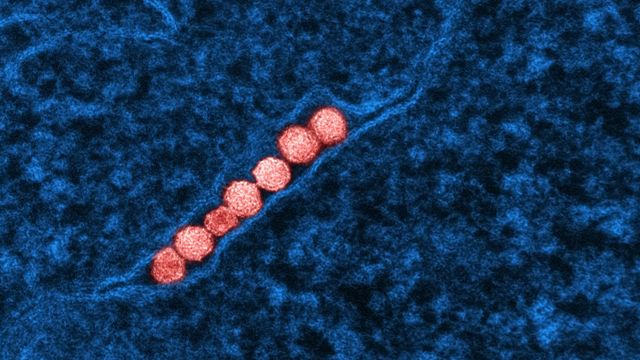

Viruses aim to hijack a cell’s protein-building machinery to replicate, but cells fight back by activating an enzyme called RNase L. This enzyme functions like molecular scissors, breaking down the materials needed for protein production.Cells respond to viral infection in a dynamic, back-and-forth manner. As one researcher described the dynamic, “It’s just like chess.The virus makes a move, the cell responds, the virus tries a new move.”

Experiments involving lung cells exposed to West Nile virus, observed under a powerful microscope with fluorescent tags, yielded several surprising findings. previously, OAS 1 was considered the primary activator of RNase L, largely based on research conducted in mice.However, this study demonstrated that it is the aggregation of OAS 3, a protein unique to humans, that truly initiates the defensive response.

redefining the Understanding of RNase L’s Mechanism

Scientists previously believed RNase L worked by dismantling ribosomes, the cell’s protein factories. This research showed that the enzyme rather targets the messenger RNA templates that ribosomes use to assemble proteins, leaving the ribosomes themselves intact.”within 30 minutes, RNase L will degrade almost all messenger RNA in a cell,” a researcher noted.

Further complicating the picture, the team found that in some cases, the release of interferon by white blood cells was sufficient to defend against West Nile virus, negating the need for RNase L to shut down protein production. this led to a significant realization: RNase L only activates when the infection overwhelms the interferon response. “This completely changes how we think about this pathway’s relation to interferon in human cells,” a researcher explained.

Future Research and Therapeutic Implications

Many questions remain unanswered. Researchers are now focused on understanding how West Nile virus evades RNase L and whether this process can be disrupted. They are also investigating whether RNase L plays a role in modulating inflammation and how other viruses,including SARS-CoV-2,adapt to this cellular defense mechanism.

While the study utilized West Nile virus as a model,researchers anticipate similar mechanisms at play in the response to other viral infections,albeit with potential variations. “This study completely changed my understanding of the RNase L pathway,” a researcher concluded. “Like a puzzle, every time you find a new piece that fits, the picture becomes clearer.”

Reference: Briggs S, Blomqvist EK, Cuellar A, Correa D, Burke JM. Condensation of human OAS proteins initiates diverse antiviral activities in response to West Nile virus. Genes Dev. 2025. doi: 10.1101/gad.352725.125