Disappointment with the system, fear of Palestinians and at the same time cruelty towards them, appear again and again in the analysis of the relations between Mizrahim and Palestinians. A policeman in front of Palestinian-Israeli protesters, in October 2000 (Photo: Flash90)

October again soon. For those who mark the death of a friend, every year, twenty-two years, the arrival of the month of death is felt a few weeks in advance. Already in August, the dates begin to remind that another year has passed since the last Memorial Day; We are getting closer to October 2nd, the day my Asil Asala member was shot dead by the police.

The events of October, during which 13 Palestinians were shot to death, including Asil, mostly occurred during the ten days of reckoning in the year 2000. For years, pent-up anger grew in me towards this month. I didn’t know who to talk to about the loss. Since publishing my personal story here on Local Talk last year, I have been given several opportunities to share it. On Memorial Day this year, for example, I will talk about October 2000 at the “House of Solidarity”.

The biggest stage given to the story in the last year is over the pages of the Guardian“ the British. The British editor I worked with posed questions to me, which made me think about Asil’s and my place in the Middle East, how to mediate this to an audience that does not know the Middle Eastern nuances: where exactly did we grow up, what languages did we speak, and finally – what class are you from? And of what class was Asil?

This is a very British question, I thought; In Israel there is no clear class discourse like in England. At first, I wrote to her, “There are really no classes in Israel”, but then I looked at the sentence and the cursor at the end of it flashed for long minutes. Are there no classes in Israel? I couldn’t believe I wrote that sentence.

In fact, since that moment I haven’t stopped thinking about the British editor’s question: What class are you from? I am the son of a Moroccan man who worked as a taxi driver and an Algerian woman who worked in the Ministry of Finance in front of Ashdod port importers; Asil was the son of Palestinian parents – an independent business owner and an educational consultant – who raised their children in the Arabah after Land Day.

Both of our families are Arab in origin, but I am Jewish and of Muslim descent. I am Israeli and a Palestinian refugee. I went to the army, Asil was shot dead by a policeman and the ambulance he was in was prevented from getting to the hospital quickly. I had the language to think in terms of differences of religion and nationality, but a question sent to me from London required me to look at this friendship in terms of class as well.

And when the ethno-class concepts began to enter my consciousness, I came across Professor Hillel Cohen’s book.

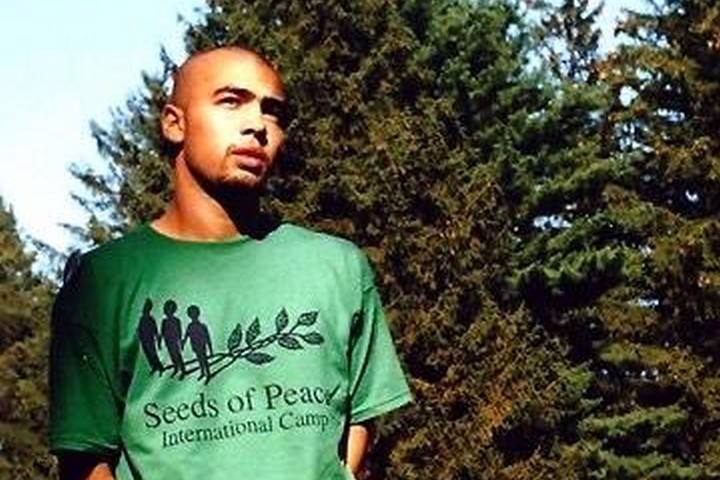

Asil Asala, a delegation of one. (Photo: Bobbie Gottschalk)

The fear of the Jewish-Ashkenazi view

I met Hillel Cohen once, at his lecture at the Van Leer Institute on settler-Palestinian relations in the occupied territories. He scattered anecdotes about “Rami Levy” branches in the occupied territories, about the Palestinians who work there, and about those who shop there.

A woman in the audience, who devoted much of her time to opposing the occupation, occasionally interrupted his words to remind those present of their political dimension – the Jews are the landlords in the places Hillel Cohen spoke about, the Palestinians suffer from oppression. It’s not that Cohen ignored the political dimension, he just didn’t insist on mentioning it explicitly in every sentence. At one point, my friend asked the woman to stop getting into Cohen’s words, and Cohen responded by saying something like: “Why do you think I have something more important to say?”

This phrase echoed in my ears when I saw two hundred copies of Cohen’s new book – “Haters: A Love Story”: About Mizrahim and Arabs (and Ashkenazim as well), from the beginning of Zionism to the events of the Palestinian Authority, which was published in “Hebrew Publishing House” – near the jams in the Annabel Cafe, on King George Street in Tel Aviv. I live not far from the Annabel Cafe, and the business there is excellent; They don’t need the additional income of a package collection point. In fact, Cohen’s new book is the only product not for sale on behalf of the cafe – no cake, no drink, no jam.

I asked the owner what was the meaning of the books taking over the shelves, and he replied that Cohen’s publisher had asked him to allow their collection. He pointed to a man in his sixties sitting outside. His skin color was like my father’s, his nose like my mother’s. Oriental man. I spoke with the publisher, Yosef Cohen, briefly while he was smoking a cigarette, and he told me that you could buy the book online and pick it up at the coffee shop.

I paid for the book in July, and for several weeks I avoided picking it up. The task the author undertook seemed impossible to me – to describe over decades the various dynamics between “Mizrahim and Arabs (and Ashkenazim as well)”.

The cover of Hillel Cohen’s book. Hebrew publishing house

The cover – two hamsas stuck together at the base of the palm – reminded me of the wink that accompanied what Cohen said in the lecture I attended. Why do you think I have something more important to say? I heard him say, and I wasn’t sure how that personal tone fit into good research writing. But I also saw the British editor’s question flicker before my eyes, what class are you from?

I thought, if the book claims to “reveal for the first time hidden cases and hidden evidence”, at least I can give it a chance. At most I won’t finish it.

Cohen writes a lot about meetings between Mizrahim and Arabs in the Levant, since the days of the Ottoman Empire. He defines an “Eastern act” as an action that the one who does it thinks of as a derivative of his Orientalism, or the one who observes it from the outside sees it as such.

According to Cohen’s analysis, there are three main types of Mizrahi operations: those that are in the service of Zionism, those that see the Palestinian Arabs as sworn enemies because of previous experiences in Arab countries, and those that try to use Mizrahi as a bridge to peace. The last group, he says, is the smallest. Too bad, I thought. Actually my group is the smallest.

I met Asil, who lives two and a half hours away from me, at the “Seeds of Peace” camp in the USA. We were forty Israeli teenagers (about a third of us Mizrahi or Palestinian) together with about a hundred from Arab countries – Qataris, Jordanians, Palestinians, Egyptians, Tunisians and Moroccans.

In LGBT culture there is the concept of “gender euphoria”, which describes a person’s ability to experience their own gender or sex in a way that feels authentic to them, that fits their experience. It is a complex concept, which in my understanding is related not only to the perception of the self, but also to society’s perception of the person, And so I borrow from him gently and carefully. Still, I think that part of what I felt in the camp was a euphoria of Arabness. I felt that there was a part of me that was expressed by being among Arab teenagers my age.

In his book, Cohen documents echoes of this feeling throughout the decades in the Levant – starting with Shimon Moyal, who spoke of a common nationalism in the pages of the “Haharut” newspaper at the end of the Ottoman Empire, to Jewish and Arab teenagers in the Jerusalem neighborhoods of Beit Tzafa and Feth in the 1970s, who became friends Or fall in love and marry. There were others like me. Not every book gives you that: a sense of community.

Of course, in Ashdod I also had friends whose families came from Arab countries. But the people I knew in the 90s didn’t hear Arabic music at home and didn’t speak the language.

Cohen points to a critical juncture in the Arabization of the Mizrahi Jews: the occupation of the territories in 1967. “The removal of the physical borders between Israel and the Territories strengthened the tendency of many Mizrahi to mark their non-Arab status… Even so, immigrants from the Mizrah were often accused of being Arabs, to symbolize their inferiority.” The fear of the Jewish view, usually the Ashkenazi, caused a renunciation of any Arab identity. what class are you Above the Arab.

You might be interested

The closeness between Mizrahim and Arabs is always an object of fear

Cohen’s book does not refer to the violent tragedy of October 2000 in the definition of an “Eastern act”. But his review of the placement of Mizrahim in units such as the MGB reminded me of the surnames of those interrogated in the Asil case, who, together with Alaa Naser, was shot to death at the Lotem intersection: policemen Hai, Shimoni, Kerso, Hatan. Not far from the shooting site, policemen Altit and Ezra. Policemen brought from different units, and sent to suppress a demonstration in an area they did not know at all; some of them isolated Asil, chased him and beat him. One of them shot him.

While reading the book, I was overwhelmed by a feeling of embarrassment, maybe even shame: how had I not thought of this before. The police officers who were questioned on suspicion of shooting Basil were Mizrahi men. I think that because they were representatives of the police, and not protesting on their own behalf in anti-Arab demonstrations such as in Acre (1961), in Samuel the Prophet in Jerusalem (1986) or in the events of May 2021 – Cohen did not refer to their actions as an “Eastern act”. But listening to their testimonies opens a window to further thinking.

Altit said: “We were called in to deal with incidents of disorder, without being equipped to provide an appropriate response, […] And apparently this created hardships for the policemen.” Chai said: “[ה]This division is not prepared, not professionally, and not with the proper equipment to respond.” Carso said: “We felt threatened and scared.”

I looked at these words, which I read over and over again in recent years, and now I couldn’t help but see that the “first line”, improvised, of the police at the Lotem junction was significantly made up of Mizrahi men, who felt frustration and even rage towards the system that sent them there.

While the police testified to themselves that they felt threatened all the time, one of the witnesses who watched them – Jobran Ne’mana, who was standing next to Asil’s mother – said that after the policemen shot Asil from behind the olive trees, they “exited impressively… as if it were the end of a movie”.

The same event, two perspectives: the Jewish-Mizrahi police officers testify to neglect by the system that sent them to Lotem and the fear they felt; The Palestinian witnesses testify that the police officers seemed confident, armed, full of purpose in the pursuit, full of pathos after the shooting.

And maybe all the things are true: disappointment with the system, fear of Palestinians and at the same time cruelty towards them, appear again and again in Hillel Cohen’s analysis of the relations between Mizrahim and Palestinians.

Prof. Hillel Cohen (Photo: Avshalom Cohen-Bar)

As someone who thinks of himself more and more as an orientalist in Israeli society, I found myself repulsed again and again by the thought that there is a history of orientalist-Palestinian enmity in this country. Then I realized that maybe the reason I didn’t want to read the book for a few weeks also lies in the title, which starts with the word “haters”. I just wanted the love story.

That youthful friendship in the 90s, which could probably only start at a distant summer camp, was loaded with identities and processes, which are slowly becoming clear to me.

Twenty years before, after the signing of the peace agreement with Egypt, the Ministry of Labor and Welfare established a team to discuss the consequences of the peace on Israeli society. The team determined that “in the absence of a capture target – an external enemy – Israeli society will find itself in a state of exposure and the disintegration trends of Israeli society as a uniquely Jewish society will increase.” That is, in the eyes of the task force, a peace process is a process that can disintegrate a “unique Jewish society”, because of the rapprochement with Arabs and Arab women. The possible closeness between Mizrahim and Arabs is always an object of fear.

At the end of the book I thought about the stories that Cohen reviewed, about relationships of enmity, love, betrayal and friendship. I could see my personal story fitting into these stories, even if Cohen didn’t write about my story directly. And in my eyes, this is a sign of a significant research and literary act: the ability to see something of the truth I know – about status, about ethnicity, about Israeliness, about Arabness – and to understand it on a historical continuum, from more perspectives and more experiences.

I’m pretty sure that in response to his question, even though it was rhetorical, Hillel Cohen has something important to say; He writes the truth. Complex, documented, relevant.

1 comment

Where can an English version of the book be obtained?