Forgotten Lung Rewrites History: 1918 Flu Virus Genome Unlocked in switzerland

Table of Contents

A groundbreaking analysis of a century-old lung sample has yielded the first 1918 influenza pandemic genome obtained in Switzerland, offering unprecedented insights into the virusS early evolution and adaptation in Europe.

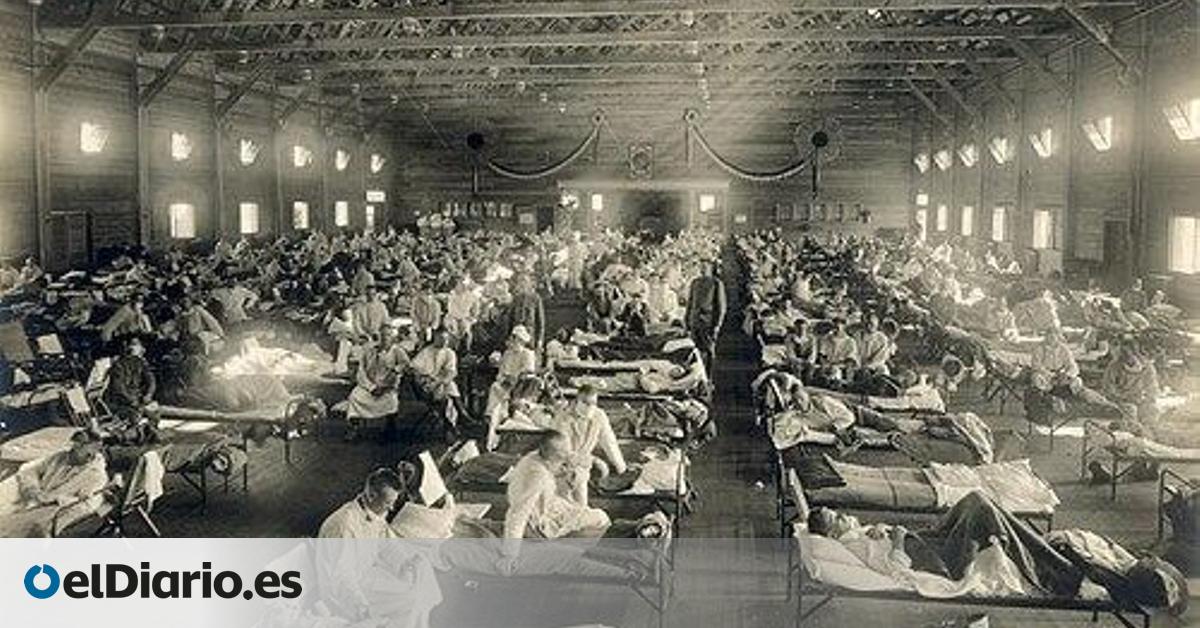

The world remembers the 1918 Spanish Flu as a catastrophe of unimaginable scale.Coffins stacked in municipal offices, overwhelmed doctors struggling to certify deaths, and newspapers filled with lists of the deceased paint a grim picture of a world ravaged by a deadly virus. Now, a century later, researchers are peeling back layers of mystery surrounding this pandemic, thanks to a remarkable finding: viral RNA extracted from a lung preserved in formalin, belonging to an 18-year-old who succumbed to the virus in july 1918 – the first wave of the pandemic.

Researchers at the University of Zurich have successfully extracted viral RNA fragments from this preserved lung,opening a new window into the virus’s origins and evolution. “This is the first pandemic genome from 1918 to 1920 obtained in Switzerland and contributes unpublished information about the adaptation of the virus in Europe at the beginning of the outbreak,” explained Verena Schünemann,the lead paleogeneticist on the study published in BMC Biology.

The team employed a elegant ligation-based sequencing method, crucial for recovering the highly degraded RNA. The genetic material of viruses deteriorates rapidly,especially when preserved in chemical substances like formalin,making this recovery a significant technical achievement. As one scientist involved in the project noted, “the old RNA is onyl preserved over time in very specific conditions, that’s why we created a new method to improve fragments recovery.”

Early Mutations Enabled Human Infection

The analysis revealed that key mutations enabling the virus to infect humans were already present in July 1918, well before the more devastating autumn wave. The research detailed how two modifications allowed the virus to evade the human immune protein Mx, while a third altered hemagglutinin – the molecule the virus uses to attach to cells. This mutation facilitated transmission, echoing a similar mechanism observed in the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2’s increased ability to bind to the ACE2 receptor in humans.

Researchers confirmed the virus was already circulating in Europe with a distinct advantage. Comparing the Zurich genome to those recovered in Germany and North America revealed a greater genetic diversity than previously understood in the pandemic’s initial stages. Fourteen differences were identified in viral proteins, especially within a key replication segment known as PB2.

The researchers emphasized that the simultaneous appearance of the same hemagglutinin variant alongside highly divergent segments, especially in PB2, represents the “first evidence of possible early reassortment in the pandemic.” This suggests the virus was already undergoing genetic mixing, possibly accelerating its evolution and spread.

The examination demonstrated that the virus circulated in Europe with adaptations that made it more effective from the outset. According to Schünemann, these results help to understand the rapid transition from an avian flu to a human pathogen and its global reach. Furthermore, the genetic variation observed in 1918 was even broader in some segments compared to the 2009 H1N1 flu pandemic virus, indicating a remarkably fast adaptation process.

Unlocking the Past to Prepare for the Future

The collaboration between the University of Basel, the University of Zurich, and the Museum of Medical History of Berlin allowed researchers to access past collections – a largely untapped resource for this type of study. “Medical collections are invaluable archives for rebuilding old virus genomes, even though their potential remains underlined,” stated Frank Rühli, a co-author of the study.

The team believes reconstructing flu genomes from over a century ago is a valuable tool for modeling future pandemics. “Understanding how viruses adapt to humans over a long period allows us to establish solid bases for prospective calculations,” explained Kaspar Staub, another author. This vision suggests that medical museums and archives worldwide could become hidden laboratories for deciphering the genetic history of viruses that continue to threaten global health.

If something makes this finding clear, it is indeed that even a forgotten lung in a bottle can rewrite what was believed true about one of the worst flu pandemics in history.