BarcelonaIn the year of Europe’s worst drought in five centuries and historic floods that left a third of Pakistan under water, the world was engrossed in the war in Ukraine. The fight against the climate crisis was taking a back seat to political agendas and government budgets, which have been focused on the arms race and mitigating the economic impact of the conflict. But not only that. The same energy crisis stemming from the confrontation between the West and Russia – the world’s second largest producer of fossil fuels – has led many countries to recover from coal and has soared purchases of liquefied natural gas to the point that, according to a report by Climate Action Tracker, the Paris Agreement knob.

But other voices, from international institutions and also experts, do not agree. “The narrative that the energy crisis will derail efforts to combat climate change is not true,” said the executive director of the International Energy Agency (IEA), Fatih Birol, in an article on the occasion of the first anniversary of the war, in which he was convinced that “the crisis will accelerate the transition towards clean energies”. Who is right? Has the war in Ukraine shot up the consumption of fossil fuels or renewables? Has it truncated the global climate fight or strengthened it?

“It has been a temporary setback, rather than a derailment of climate goals, and at the same time it is a reminder that the energy transition will not be a smooth process”, says Ben Cahill, specialist in energy security and climate change at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). He admits, however, that one of the “unfortunate consequences of the crisis” has been the recovery of coal, especially in countries in Asia that “have stopped buying natural gas because the prices were too high and have chosen to burn more Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh are some of them, but also – and much more importantly – China, which last year surpassed even its own coal consumption peak, which was in 2013. ” The whole energy transition depends on reducing coal as soon as possible in electricity production,” says Cahill. And this consumption has risen in the last year on a global scale, mainly due to this rise in Asia and also in countries like Germany, which has reopened coal mines to replace the loss of Russian gas.

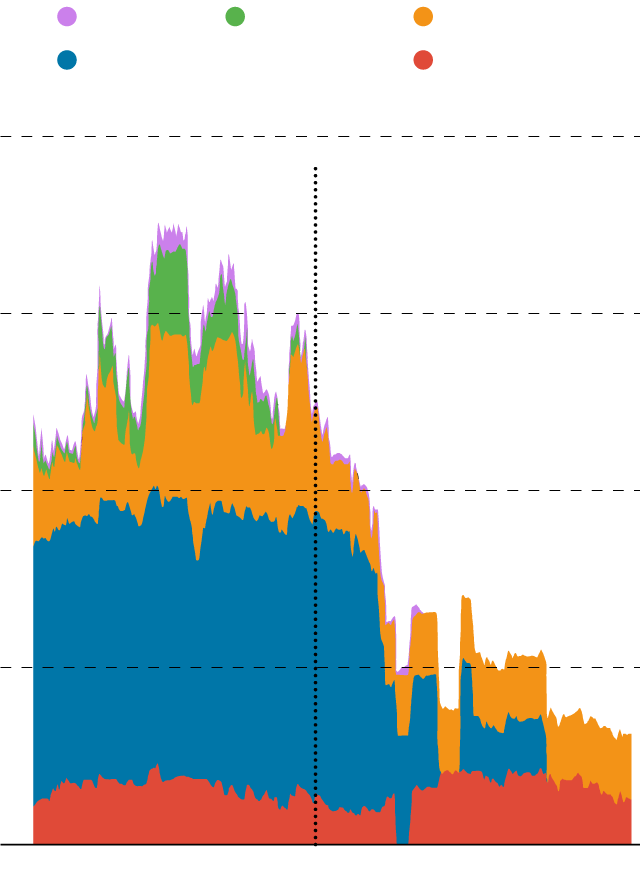

Global investment in the supply of oil, gas and coal

Investment by source type, 2015-2022. Data in billions of US dollars

But what has replaced Russian gas in Europe in general has not been coal, but liquefied natural gas (LNG). “Clearly, I think the big winners are the gas companies of the United States” because “their LNG, which arrives by boat, has come to stay for a long season”, says Aurèlia Mañé, professor at the UB and expert in relations international energy. LNG, mainly from the United States but also from Qatar and Nigeria, already represents 25.7% of European gas imports. Then comes gas from Norway (24.9%), Russia (24.6%; previously it was 40%) and Algeria (11%). And this LNG imported from the USA “has an environmental problem that Russian gas did not have” and that is that “it comes from fracking, an extraction method that is much more polluting and territorially extensive”: “In addition, it is transported by ship and the fuel used is also highly polluting”, adds Mañé.

In the same year that Joe Biden’s administration approved the most important climate package in US history, the US fossil fuel sector was growing thanks to European demand. The American LNG industry, in fact, has grown steadily since it was born in 2016 and has long positioned the United States as the world’s number one producer of fossil fuels. But, according to Cahill, much of the gas that has landed in Europe has done so because demand for LNG in Asia fell and Europe was paying a very high price for it. “Many of the volumes that would have been consumed by China have ended up in Europe”, he explains, but last year China was still in confinement due to covid-19. Now that it’s out, its return to the LNG market could complicate Europe’s situation next winter.

Liquefied natural gas imported from the US has an environmental problem that Russian gas did not have, because it comes from fracking, a much more polluting and territorially extensive extraction method.”

Aurelia Mañé Professor at the UB, expert in international energy relations

A new energy crisis?

Cahill warns that the energy crisis and the rise in gas prices – which are currently falling – may be repeated this year. First, for the recovery of China, which will compete with the EU for gas. And also because Europe, last year, was still able to feed its reserves with Russian gas. Moscow did not cut Nord Stream until June. Since then, the flow of Russian gas to Europe has indeed dropped by 80% from pre-war levels. But the entire first part of the year 2022 was still to come. That won’t be the case next winter, which may not be as mild as the one we just had, he says.

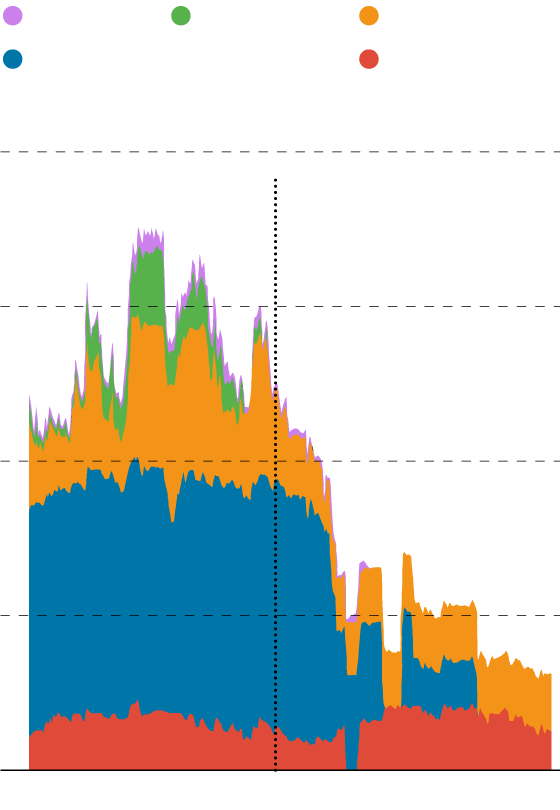

Flow of natural gas from Russia to Europe

Volume of natural gas destined for the EU and Turkey from January 2022. Data in mcm/d according to the channel

Russian invasion of Ukraine

Russian invasion of Ukraine

Russian invasion of Ukraine

Europe will bet on LNG again. But another problem is that “LNG plants can have a life of 40-60 years”, as the director of the Global Carbon Project and author of the IPCC, Pep Canadell, explains. And the world cannot continue to consume gas for another half century if it wants to avoid the worst effects of the climate crisis. The classification of gas as “green energy” by the European Union and which encourages investment in this fuel has played an important role here. But Cahill assures that the construction of new regasification plants, which have been launched in Europe and will not be operational until 2026, does not involve such prolonged gas consumption, because in most cases “they are temporary terminals that they can be used for a few years for LNG and then they can be rented for other uses”.

The American expert assures, in fact, that “even in the scenario of a faster transition towards clean energy, it will be necessary to use natural gas for another two decades”, because it is very difficult to replace it in large industry (for electricity and transport, the transition to renewables is easier). Cahill insists that “it’s not one thing or the other” – renewables or gas -, but both will have to coexist for a certain time “to guarantee energy security”. An opinion that is officially shared by the EU, and that also applies to nuclear energy, which has also regained momentum following the war.

Investment in clean energy is growing.

Annual investment in clean energy, 2017-2022. Data in billions of US dollars

Annual variation of investment in clean energy by country groups

Data in billions of US dollars, 2020-2022

But not everyone agrees. “The rhetoric of gas as green energy has been around for ten years and it has been seen that it displaces investments in renewables, and that it is friendly to the climate only in part. Despite being the fossil fuel that emits the least, if you look at the entire methane extraction chain [que se’n desprèn i és un potent gas d’efecte hivernacle] it has many impacts”, says Alfons Pérez, engineer and energy specialist at the Global Debt Observatory. In this war-torn 2022, investment in clean energy has continued to grow, but in Western powers the rise has been half as big as it was in 2021, IEA data show.

Another effect of the energy crisis resulting from the war in Ukraine has been the momentum of the debate on hydrogen as an alternative, but Pérez warns that fossil fuel companies are often behind it. “The Next Generation funds were mainly dedicated to green projects and most hydrocarbon companies couldn’t get in. How did they get in? Through green hydrogen,” he says. But many experts are already warning of the “very low efficiency” of hydrogen because, in reality, “it is not a source of energy, but a way of storing it”. To generate hydrogen, a lot of energy is still needed, and from renewable sources it is not cost effective in many cases. For Cahill, hydrogen “may be a long-term solution for industry, but not for other sectors.”

The only thing that remains clear, after the crisis, is that the energy transition will not be easy. It may not have derailed yet, but the world can’t afford any more theft. We only have this decade – now it’s time to accelerate.