The demographic landscape in contemporary society presents a concerning paradox: declining fertility rates juxtaposed against rising obesity prevalence. This contradiction is particularly pronounced in China, as noted by Chen19necessitating heightened vigilance regarding maternal safety during pregnancy. The HDP represents an unavoidable challenge in obstetric practice, ranking among the most common complications and potentially culminating in life-threatening sequelae including cardiac failure, placental abruption, and eclampsia. Despite their clinical significance, the pathophysiological mechanisms and predictive indicators of these disorders remain incompletely elucidated, underscoring the importance of identifying modifiable factors influencing blood pressure regulation during gestation.

Weight assessment constitutes a routine and relatively objective component of antenatal surveillance, comparable to fundal height and abdominal circumference measurements but with reduced vulnerability to observer bias. Excessive gestational weight gain may signify not only pathological fluid retention and hypoalbuminemia—indirect markers of disease progression in hypertensive disorders—but potentially reflects suboptimal dietary discipline and health behaviors. Additionally, cultural factors influence maternal nutrition, particularly in Chinese society where traditional perspectives emphasize fetal well-being, potentially encouraging excessive maternal nutritional intake without adequate consideration of potential adverse maternal consequences. Given the established role of obesity in the pathogenesis of both essential hypertension and pregnancy-specific hypertensive disorders, our investigation sought to characterize the quantitative relationship between maternal weight and blood pressure during pregnancy, with the goal of emphasizing the importance of appropriate weight management.

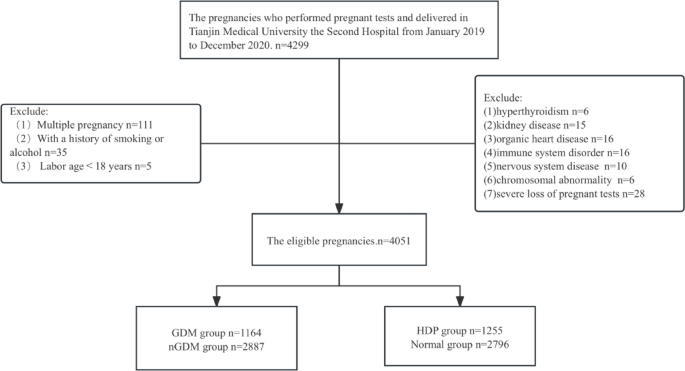

Tianjin, a coastal metropolis in northern China, is characterized by dietary patterns high in carbohydrates and sodium, predisposing the population to obesity-related conditions. As a regional referral center for high-risk pregnancies, our institution manages substantial numbers of women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (30.98%, n = 1,255/4,051) and gestational diabetes mellitus (28.73%, n = 1,164/4,051), providing a robust cohort for investigating these relationships. Our data revealed that 34.90% of women were overweight or obese at their initial antenatal visit, reflecting the concerning prevalence of elevated body mass index in our obstetric population.

The mean gestational weight gain in our cohort was 13.54 kg, with no significant difference observed between normotensive women and those with hypertensive disorders (13.35 kg versus 13.60 kg, p = 0.08). This finding suggests generally appropriate weight management across both groups, likely attributable to consistent antenatal counseling and patient adherence to recommended guidelines. In examining the longitudinal patterns of weight and blood pressure throughout pregnancy, we observed persistent weight gain from conception through delivery, consistent with the expected positive nitrogen balance of gestation (Fig. 2). In contrast, blood pressure demonstrated the characteristic mid-pregnancy nadir (Fig. 3) previously documented in our research15. This divergence in trajectories suggests that while weight contributes to blood pressure regulation during pregnancy, additional physiological mechanisms substantially influence hemodynamic parameters.

To elucidate the relationship between maternal weight and blood pressure while accounting for potential confounding factors including maternal age, gestational weight gain, and neonatal birthweight18we performed covariance analysis. This revealed a significant but modest correlation between maternal weight and both systolic (r = 0.322, p r = 0.304, p 4). Comprehensive analysis incorporating all antenatal measurements demonstrated a moderate correlation between maternal weight and blood pressure parameters (r = 0.427 for systolic and r = 0.397 for diastolic blood pressure, p 4; Table 5).

Several pathophysiological mechanisms may explain these observed correlations. First, gestational weight gain can induce excessive insulin secretion and insulin resistance. The resulting hyperinsulinemia may enhance renal sodium reabsorption and stimulate the sympathetic nervous system, contributing to blood pressure elevation22. Second, increased adipose tissue, particularly visceral deposits, secretes diverse functional adipocytokines including non-esterified fatty acids, leptin, angiotensinogen, endothelin, interleukin-6, and renin23. These bioactive molecules collectively influence blood pressure regulation by enhancing α1-adrenoreceptor vasoreactivity while simultaneously reducing baroreflex sensitivity, vascular compliance, and endothelium-dependent vasodilation24.

Additionally, gestational weight gain is frequently accompanied by dyslipidemia, which may exacerbate inflammatory processes and endothelial dysfunction. These pathophysiological alterations potentially contribute to preeclampsia-like phenomena and subsequent blood pressure elevation25,26. It is noteworthy that obesity directly impacts myocardial contractility and diastolic function, increasing cardiac workload and potentially exacerbating existing hypertensive conditions. The more pronounced effect observed for systolic compared to diastolic blood pressure (0.47 mmHg versus 0.325 mmHg per kilogram) likely reflects the greater impact of these mechanisms on cardiac output rather than peripheral vascular resistance27.

These findings suggest that appropriate weight management may contribute meaningfully to blood pressure control during pregnancy. Conversely, maintaining blood pressure within recommended ranges may help mitigate pathological fluid retention and albumin loss associated with excessive gestational weight gain28. The bidirectional nature of this relationship merits consideration in clinical management protocols for pregnant women, particularly those at elevated risk for hypertensive complications.

Based on the established pathophysiology of obesity, we hypothesized that women with gestational diabetes mellitus and hypertensive disorders would demonstrate stronger correlations between weight and blood pressure due to their pronounced insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction. Surprisingly, our results revealed no significant difference in this relationship between women with and without gestational diabetes mellitus (Figs. 5 and 6; Table 5). This unexpected finding may reflect the more intensive dietary counseling and weight management typically provided to women with gestational diabetes, potentially mitigating the adverse hemodynamic effects of excessive weight gain.

Perhaps the most notable finding from our subgroup analysis was the markedly attenuated correlation between maternal weight and blood pressure in women with chronic hypertension. In this population, maternal weight demonstrated only a weak correlation with systolic blood pressure (r = 0.202) and virtually no relationship with diastolic blood pressure (r = 0.095) (Figs. 7 and 8; Table 5). This distinct pattern likely reflects the fundamentally different pathophysiology of chronic hypertension compared to gestational forms, particularly regarding reduced vascular elasticity and diminished responsiveness to adipocytokines29. Women with longstanding hypertension typically exhibit structural vascular changes and altered baroreceptor sensitivity that may render blood pressure regulation less dependent on fluctuations in maternal weight.

Our analysis further revealed that correlations between weight and blood pressure in women with gestational hypertension and normotensive pregnancies were comparable. This observation may be attributable to appropriate gestational weight gain across our cohort, as well as the potential mitigating effects of antihypertensive and vasodilatory therapies in women with gestational hypertension. These therapeutic interventions may attenuate blood pressure fluctuations and potentially obscure the influence of maternal weight on hemodynamic parameters.

Our investigation has several limitations that warrant acknowledgment. First, our pregnant test materials lacked comprehensive third-trimester data, as this information was recorded in patient-held pregnancy handbooks rather than institutional electronic databases. This data gap potentially limits our understanding of weight-blood pressure relationships during the critical final weeks of gestation. Second, while our analysis identified significant correlations between maternal weight and blood pressure, the modest coefficients of determination indicate that weight represents just one of many factors influencing blood pressure during pregnancy. The multifactorial nature of blood pressure regulation is reflected in the relatively low R² values, suggesting that comprehensive blood pressure management requires consideration of multiple physiological and environmental factors beyond weight alone.

Future investigations should incorporate additional hemodynamic parameters, including cardiac output, systemic vascular resistance, and biomarkers of endothelial function, to develop more comprehensive models of blood pressure regulation during pregnancy. Prospective studies with standardized measurement protocols and detailed assessment of dietary patterns, physical activity levels, and psychological stressors would further elucidate the complex interplay between maternal weight and blood pressure during gestation. The integration of advanced techniques for body composition analysis, including assessment of visceral adiposity, might provide more nuanced insights regarding the specific adipose depots most strongly associated with adverse hemodynamic effects.

Despite these limitations, our findings have meaningful clinical implications. The quantifiable relationship between maternal weight and blood pressure suggests that appropriate weight management represents a modifiable factor in the prevention and management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. The observed differences across hypertensive subgroups indicate that weight management strategies may be particularly beneficial for women with gestational forms of hypertension rather than those with chronic disease.

Decoding the Pregnancy Paradox: Weight, Blood Pressure, and Maternal Health – Expert Insights

Time.news Editor: Welcome, everyone. Today, we’re diving into a fascinating yet concerning trend: declining fertility rates coinciding wiht rising obesity, and its potential impact on maternal health. We’re joined by Dr. Eleanor Vance, a leading expert in Maternal-Fetal Medicine, to unpack a recent study focusing on this very issue in China. Dr. Vance, thank you for being here.

Dr. Eleanor Vance: My pleasure. I’m happy to shed some light on this critical area.

Time.news Editor: The study highlights a paradox: lower fertility rates alongside rising obesity,especially in China. This presents unique challenges for maternal safety during pregnancy. Can you elaborate on the specific concerns surrounding Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy (HDP) in this context and its preeclampsia implications?

Dr. Eleanor Vance: Absolutely. HDP, including gestational hypertension and preeclampsia, are major complications during pregnancy and is a notable contributor to maternal morbidity and mortality in China and also globally.the study is emphasizing that while these conditions are common and serious, we still haven’t fully unraveled their root causes. A critical aspect of this inquiry is that weight has a modifiable factor in regulating blood pressure. The correlation between obesity and those complications are well established, and pre-pregnancy excessive weight is a great concern.

time.news Editor: The research emphasizes the role of weight assessment as a routine part of prenatal care. beyond just identifying potential issues like fluid retention,what is the importance of gestational weight gain and how do cultural factors influence maternal nutrition,particularly in China?

Dr.Eleanor Vance: Exactly, weight monitoring is a very practical element of routine care of pregnant women. The study correctly emphasizes how easily it can be measured. from a high level outlook,it can provide us a glimpse of general health behaviors.

The study also highlights a key takeaway for maternal nutrition. In China, culturally there is a strong emphasis on adequate nutrition for the baby and as a result, can lead to excessive caloric intake for mothers, without an understanding of the possible negative maternal impact.

Time.news Editor: This study centered around Tianjin,a coastal city in China. What makes this region a good case study for investigating the relationship between weight and blood pressure in pregnancy?

Dr. Eleanor Vance: Tianjin’s dietary habits, characterized by high carbohydrate and sodium intake, make its population more susceptible to obesity-related conditions. The hospitals manage quite a number of hypertension in pregnancy and gestational diabetes,therefore,it provides a large pool of people to study,which allow accurate statistical analysis and meaningful results.

Time.news Editor: The study found that while there was weight gain throughout the pregnancy, blood pressure followed a diffrent pattern, dipping in the middle. What does this divergence suggest about the relationship between maternal weight and blood pressure during pregnancy? Is there relationship between the two?

dr.Eleanor Vance: That’s a crucial observation. It tells us that while weight plays a role, blood pressure regulation during pregnancy is complex and multi-faceted which is a critical point in helping expectant mothers understand what to expect during a pregnancy. There are other physiological mechanisms at play, like hormonal changes and cardiovascular adaptations, that override the direct impact of weight in the second trimester. However, the study did confirm a moderate correlation between maternal weight and blood pressure across all antenatal measurements so appropriate weight management is still an important factor.

Time.news editor: You mentioned cardiovascular adaptations and the study also digs into the pathophysiological mechanisms that link weight and elevated blood pressure, mentioning things like insulin resistance and adipocytokines. Can you break that down for our readers who might not be familiar with the terminology?

dr. Eleanor Vance: Of course. Think of it this way: Weight gain, especially excessive weight gain, can disrupt the body’s normal processes.

Insulin Resistance: Excess weight, through excess insulin, can lead to renal sodium reabsorption and stimulate the sympathetic nervous system, ultimately raising blood pressure.

Adipocytokines: Fat tissue releases a variety of molecules, like hormones and inflammatory factors, that affect blood vessel function and blood pressure control.

dyslipidemia: Excessive fat leads to high cholesterol which in turn contribute to inflammation leading to blood pressure elevation.

Time.news Editor: The research also found that the correlation between weight and blood pressure differed across various subgroups,like those with chronic hypertension versus gestational hypertension. why is this significant?

Dr. Eleanor Vance: this is a vital insight for how doctors approach weight management advice. It suggests that weight management will more than likely benefit women going into pregnancy with gestational forms of hypertension, rather than with chronic diseases. we can infer that women with longstanding hypertension may have structural vascular changes,thus less dependent on maternal weight.

Time.news Editor: What do you think are the clinical implications of this study?

Dr. Eleanor Vance: The study underscores the importance of appropriate weight management as a modifiable factor to help prevent and manage hypertensive disorders. We need to provide tailored guidance for women based on the specific type of hypertension they have.

Time.news Editor: So,what practical advice can you give to women who are planning to become pregnant or are already pregnant,given the findings of this study?

Dr. Eleanor Vance: I would give the following points to women who are planning to become or are already pregnant:

- Pre-conception Counseling: Ideally, see your doctor before you get pregnant to discuss your Body Mass Index (BMI) and develop a plan for achieving a healthy weight.

- balanced Diet: Focus on a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, lean protein and whole grains. Limit processed foods, sugary drinks, and excessive salt.

- Regular exercise: Engage in moderate-intensity exercise*, such as brisk walking or swimming, as recommended by your doctor.

- Regular Prenatal Care: Attend all scheduled appointments so your doctor can monitor your weight, blood pressure, and overall health.

- Cultural sensitivity: Be aware of cultural influences on your diet and make informed choices for you and your baby.

Time.news Editor: Dr. Vance, this has been incredibly informative. Thank you for sharing your expertise with us today.

Dr. Eleanor Vance: It was my pleasure. I hope this information empowers women to take proactive steps towards a healthy pregnancy.