Updated:05/06/2022 00:26h

Save

the old emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar II He had a majestic air, a great palace, the blood of Genghis Khan and Tamerlane in his veins and he continued to squander luxury in his parades through the city of Delhi. But nothing more. The British had been stripping him of his power until turning what, according to the signed agreements, was a feudal lord of those lands into a mere chess king, a subject with airs not of the British Empire, but of a private company based in London . A mutiny in 1857 would change everything for Zafar and allow him to recover from the humiliations, although the price he had to pay in return was very painful for his people and for him.

After revisiting the origins of the Company of the Indies in ‘Anarchy’ and the British disaster in Afghanistan in ‘The Return of the King’ (both edited by Desperta Ferro), the Scottish historian William Dalrymple is now publishing a book in Spain, also with this publisher, ‘The Last Mongol’, about the twilight of an ancient dynasty due to its role in the Indian Mutiny of 1857. Using twenty thousand documents from Indian archives, Dalrymple gives a totally different view of this rebellion, without the British nationalist veneer and crude anti-colonialism that serves to remember what happens when you build an empire based on shortcuts.

a business empire

At the beginning of the 17th century, England was a second-class nation and resigned to taking the crumbs that Spain and Portugal left unguarded in their abusive control of oceans, islands and continents. However, at that time a group of disinherited Londoners organized themselves into a small initiative that, far from the facilities offered the east coast of north america, wanted to follow the example of the successful Dutch adventure in the Pacific. Unlike the Spanish model, where the colonizing baton was carried by the Crown, the Dutch opted for the merchants to prosper as they pleased in the most distant ports.

In the heat of Dutch benefits, the British East India Company took the capitalist experience to the next level. The first merchants arrived in India fearful of the Great Khan, but they soon let go of their tails as this private company, with more soldiers under its command than the British Monarchy itself, was eliminating its French competitors and taking advantage of the disagreements between the different Indian kingdoms, torn by religious and racial issues. The result was an exercise in total disregard for local sensitivities.

The politician Edmund Burke (1729-1797) denounced in the British Parliament the painful passage of this company through the country:

“The Tatar invasion was harmful, but it is our protection that destroys India. Before it was enmity, today it is our friendship. our conquest there […] it is as raw as it was on the first day. The natives hardly know what it is to see the gray hair of an Englishman. Young people, almost boys, govern there, without treatment and without any consideration for the natives. They have as much social contact with the town as if they still lived in England, just enough to amass a quick fortune. […]. Every rupee of profit made by an Englishman is forever lost to India. We do not provide any type of compensation […]. England has not built churches or hospitals or palaces or schools or bridges or roads or waterways or dams. Every other conqueror before him has left some monument behind him. If we were expelled from India nothing would be left to witness our presence during the ignominious period of our rule in nothing better than the rule of an orangutan or a tiger.

The so-called sepoys they nurtured the infantry that sustained the Company’s military power for decades over the European troops themselves, who were a minority and also had a mercenary nature. The discontent of the local population was growing with the abusive laws of the British, which marginalized those who were not European, the indiscriminate exploitation of resources, the introduction by force of Western customs and the famines that some regions suffered, in another prosperous time.

The Sepoys were no strangers to this growing anger. However, the trigger for the 1857 rebellion, whose epicenter was in a town northwest of Delhiwas related to such a shallow motive as the introduction of a new muzzle-loading rifle that used an oiled membrane, rumored to be made from the fat of cows or pigs, something offensive to both Hindu soldiers and Indians. the Muslims.

Skip the riot because of the cows

The British claimed that the fat was not from animals, but the rumor persisted and caused an unexpected outburst of fury in several barracks against their officers. They freed prisoners and attacked European enclaves in the area, killing all non-Indians in their path. In one of the great foci, the rebel forces were defeated by the British forces of Meerutwho made the mistake of letting them out alive on their escape to Delhi.

On May 11, 1857, the rebels reached the Red Fort and joined other rebels in their search for a leader who would unite them all against the British. Ironically, as Dalrymple points out in the book, although 85% of these rebels were Hindus, they turned in a moment of desperation to the Mongol emperor, who was a very tolerant leader, but a Muslim. “It’s fascinating that he kept that attraction as a symbolic figure. What does this tell us about the inclination of the people towards the Mughals a century and a half ago? Without a doubt, it gives us a glimpse of a completely different set of perceptions about Mughal rule, ”says the writer in a statement collected by the publisher.

The entrance of the sepoys in Zafar’s palace interrupted the placid life of the emperor. Calligrapher, Sufi, theologian, patron of painters, garden designer, and highly regarded poet, Zafar was many things, but he was not a man of action, nor a great military man. His first reaction was to be horrified at the sight of the brutish soldiers asking him for help, but then he made the risky decision to approve the uprising. Zafar’s blessing transformed what at first seemed like a simple mutiny into the largest uprising the British Empire had ever had to put down.

139,000 sepoys (nearly half of all company forces) joined the rebellion concentrated in the north of the country. The presence of such a large army in the city caused a serious problem of public order and logistics from the beginning. There was no food for so many mouths and the army was divided into many factions, each led by a warlord with its own demands on him. Zafar never got control over his troops and on more than one occasion he threatened to resign and retire to Mecca if they did not obey him. The soldiers dedicated themselves to raiding the houses of moneylenders and looting the bazaars, while the price of staple foods like legumes, rice and peas went through the roof. The famine hit the poor first, then the middle classes, and finally the troops.

By July, the 100,000 Sepoys gathered in Delhi were a starving mass of men who were disintegrating more and more every day. There was no food, no money, no weapons, and morale was rock bottom, with the emperor showing no sign of having a plan. Soon the few British, less than 10,000, that the Company had on the ground came to claim the dam. With this force and 100,000 mercenaries mostly from Pakistan, the Europeans surrounded Delhi in what was hell on earth.

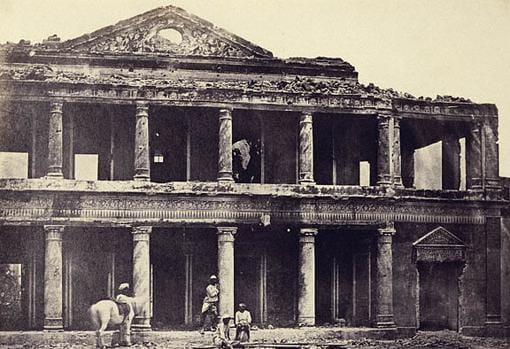

“The site of Delhi was the Stalingrad of the Raj: a fight to the death between two powers, neither of which could step back. Casualties were unimaginable, and combatants on both sides were pushed to the limits of their physical and psychological endurance,” explains the author of ‘The Last Mongol’. Massive siege cannons, each drawn by twelve elephants, prepared by mass bombardment the ground for an assault they imagined would be a doddle given the desperation of the defenders. Nothing is further from reality. Lthe sepoys were famished and many had returned to their villages, but the survivors organized street-by-street resistance, with snipers, shrapnel and booby traps on every corner of the labyrinthine city.

Of the 100,000 men with which the British stormed the city, a third were killed or wounded on the first day, “a catastrophic casualty rate on a par with the fiercest battles in history.” First World War». The other two-thirds of the British contingent ended the day in an unfortunate state of intoxication that predicted a very long siege. In the midst of the confusion, three days later, on September 17, a solar eclipse occurred that darkened the city by day, which was interpreted by Hindus as a sign of bad omen. That night, the sepoys flee the city in a great uproar, leaving the emperor without guard.

The British entered the city wiping out all life they encountered. “When the enraged lions entered the city, they killed all the weak and defenseless and burned their houses. Mass murder spread everywhere and horror gripped the streets. Perhaps these atrocities always occur after a conquest, “said a witness to the events.

Abandoned by all, Zafar was forced to leave Delhi in a humiliating bullock cart to go into exile in Burma (present-day Myanmar). Upon his death in November 1862, the authorities expressly forbade laments or eulogies for the deceased: “There should be no trace to distinguish the place where the remains of the last Mughal rest.”

The British Crown seized the government from the East India Company after having repeatedly acted so irresponsibly and formed a raj in india that would last 90 years. The new authorities abolished the occupation of land, decreed religious tolerance and opened the doors for the Indians to have a greater role in the different institutions of the country, although always as subordinates of the British.

See them

comments