Will Putin ever Face Justice? The Murky Future of Europe’s Ukraine War Crimes Tribunal

Table of Contents

- Will Putin ever Face Justice? The Murky Future of Europe’s Ukraine War Crimes Tribunal

- The Aspiring Goal: Holding Russia Accountable

- Echoes of Nuremberg: A Troubling Comparison

- A Court with Limits: National vs.International

- The ICC’s Shadow: A Prior Indictment

- Why Create a New Court? The ICC’s Failings

- A Missed Opportunity: reforming the ICC

- A law for Russia, But Not for Others

- The Stranded Whale: A Bleak Outlook?

- FAQ: Understanding the Special Tribunal for Ukraine

-

- What is the Special Tribunal for the Crime of Aggression against Ukraine?

- why is a new tribunal needed when the ICC already exists?

- can the tribunal arrest Vladimir Putin?

- Will there be a trial even if Putin isn’t present?

- is the tribunal widely supported internationally?

- What are the chances of the tribunal actually holding a trial?

-

- Pros and Cons of the Special Tribunal for Ukraine

- Will Putin Ever Face Justice? A Deep Dive into the Ukraine War crimes Tribunal

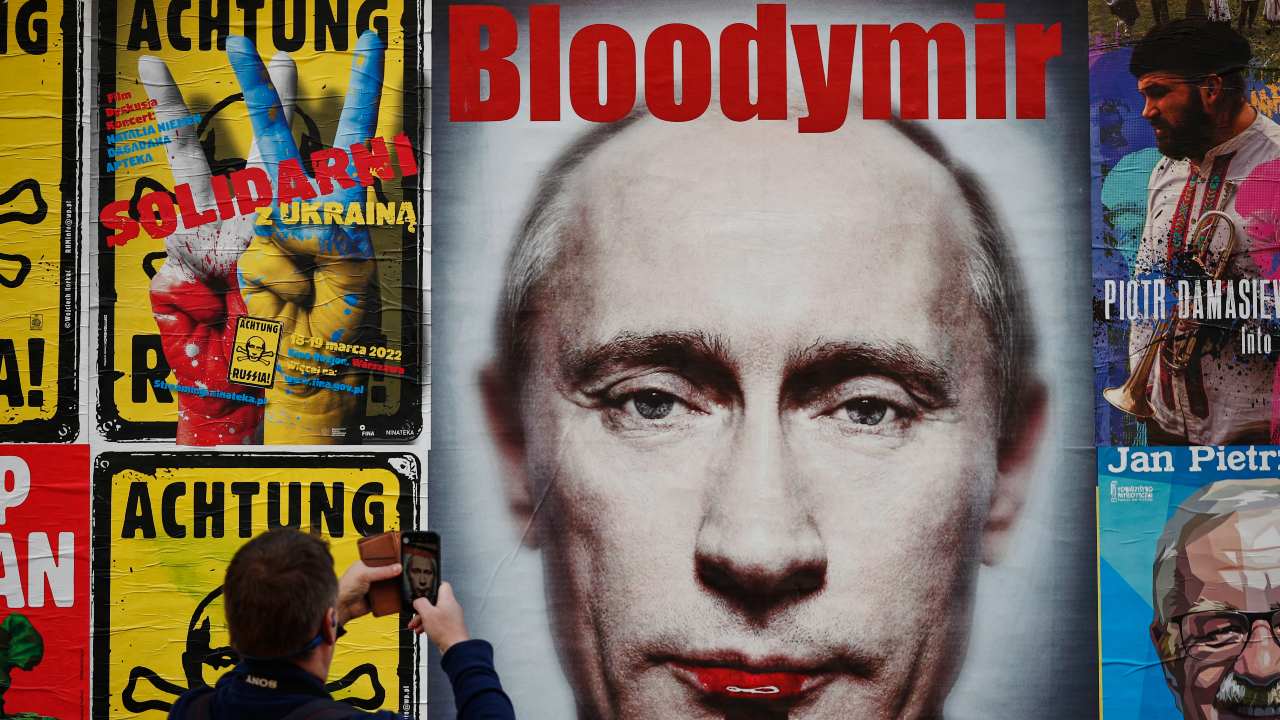

Is Europe’s new court for Ukraine, designed to prosecute Vladimir Putin for the crime of aggression, destined to become another well-intentioned but ultimately toothless international body? Like Churchill’s “stranded whale,” this tribunal faces meaningful hurdles that could prevent it from ever holding a trial.

The Aspiring Goal: Holding Russia Accountable

Launched with considerable fanfare and the support of 38 nations, the Special Tribunal for the Crime of Aggression against Ukraine aims to prosecute putin and his ministers for the invasion. The idea is simple: the UN Charter prohibits wars of aggression unless they are defensive or authorized by the UN Security Council. Russia’s invasion meets neither criterion.

Supporters argue that the tribunal fills a crucial “accountability gap.” While the International Criminal Court (ICC) has charged Putin with crimes against humanity related to the *conduct* of the war,it doesn’t address the *legality* of the war itself. This new tribunal aims to do just that.

Quick Fact: The crime of aggression is considered one of the most serious international crimes, alongside genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity.

Echoes of Nuremberg: A Troubling Comparison

The tribunal is being hailed as the first court to prosecute the crime of aggression as the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials after World War II. But this comparison highlights the challenges. Nuremberg and Tokyo had defendants in custody and access to enemy documentation. The new tribunal likely will have neither.

Russia’s leaders are unlikely to surrender themselves.Furthermore, unlike post-war Germany and Japan, Russia is not occupied, meaning the tribunal will have no access to Russian files. Proving that Putin and his inner circle exercised command functions in the invasion requires evidence that may be impractical to obtain.

Did you know? The Nuremberg trials established the principle that individuals can be held accountable for international crimes, even if they acted on behalf of their state.

A Court with Limits: National vs.International

The tribunal will be based in The Hague, with a panel of 15 international judges, prosecutors, and even a jailhouse. It will be administered by the Council of Europe, which also oversees the European Court of Human Rights. Though, crucially, it will operate as an extension of Ukraine’s court system, taking its orders from Kyiv.

This national character has significant implications. as the tribunal’s own briefing papers admit, it cannot arrest Putin or his ministers, even if they were to appear in The Hague. As heads of state, they enjoy sovereign immunity from national courts.

The tribunal’s only hope is to wait until Putin and his colleagues leave office and then travel to one of the council of Europe’s 46 member states. This is a long shot, to say the least.

The Problem of Recognition

Most of the world does not recognise the court. Despite intense lobbying, states in Africa, Asia, and South America have largely shunned it. The United States initially backed the tribunal under the Biden management, but a potential Trump return could reverse that support, leaving it as a primarily European endeavor.

expert Tip: International legitimacy is crucial for the success of any war crimes tribunal. Without broad support, the court’s decisions might potentially be seen as politically motivated and lack the moral authority to compel compliance.

The ICC’s Shadow: A Prior Indictment

Even if Putin were to leave office and travel to Europe, the tribunal faces another hurdle: the ICC’s prior indictment. The tribunal cannot try him until the ICC has completed its proceedings. This creates a potential bottleneck, further delaying any prospect of justice.

The Council of Europe has attempted to circumvent this problem by allowing trials *in absentia* – holding a trial without the defendant present. This is a controversial practice, as it deprives the accused of the right to defend themselves. Many countries that endorse the tribunal prohibit trials *in absentia* in their own courts.

Reader Poll: Should trials *in absentia* be allowed in international war crimes tribunals, even if it means possibly sacrificing due process?

Why Create a New Court? The ICC’s Failings

Given these limitations, many question the need for a new court, with an estimated annual budget of $60 million, when the ICC already has the jurisdiction to try Putin for the crime of aggression. the ICC’s reputation, however, is in decline. In its 22-year history, it has only convicted six war criminals and has been plagued by scandals, including a recent sex-harassment investigation of its chief prosecutor.

Moreover, the ICC faces significant restrictions on prosecuting the crime of aggression. Most of its 125 member states have secured immunity from prosecution for this particular crime. Court rules also prohibit aggression charges against countries that are not members, like Russia.

A Missed Opportunity: reforming the ICC

Former ICC chief prosecutor Luis Moreno Ocampo has argued that simply rewriting a few paragraphs of the ICC Statute would allow it to prosecute Russia for the crime of aggression,eliminating the need for the new tribunal. The ICC is holding a review conference this July,which could potentially make this change.

However, such a change is unlikely. World leaders are hesitant to expand the ICC’s powers to crimes of aggression, as it could threaten too many governments. This reluctance reveals a deeper truth about international justice: it is indeed frequently enough selective and politically motivated.

The american Outlook: A Double Standard?

Consider the case of former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown, a vocal advocate for the new tribunal.If the tribunal’s mandate were not limited to Ukraine, he could face scrutiny for the wars in Kosovo and Iraq, neither of which had UN permission and would be tough to argue were defensive. The same could apply to the other 31 states that participated in the 2003 invasion of Iraq, including the United States.

this highlights a potential double standard. While the U.S. supports holding russia accountable for its aggression in Ukraine, it is indeed wary of setting a precedent that could expose its own leaders to similar scrutiny. This tension between principle and self-interest is a recurring theme in international law.

Real-World Example: The debate over the ICC’s jurisdiction has long been a point of contention in U.S. foreign policy. The U.S. has historically resisted joining the ICC,fearing that its soldiers and officials could be subject to politically motivated prosecutions.

A law for Russia, But Not for Others

European states have carefully limited the new tribunal’s mandate to Ukraine, and Ukraine only. In effect, they have created a law that applies to Russia, but not to themselves. This selective application of justice undermines the tribunal’s credibility and raises questions about its true purpose.

Human rights groups insist the tribunal is a worthy cause, as it expands the reach of war crimes justice. Ukraine also supports it, seeing it as a way to share the burden of its ambitious war crimes investigations. However, the ultimate test will be whether the tribunal can bring suspects to trial.

Quick Fact: Ukraine is currently investigating thousands of alleged war crimes committed by Russian forces on its territory.

The Stranded Whale: A Bleak Outlook?

If the tribunal fails to hold a proper trial, it risks becoming a symbol of international justice’s limitations – a well-intentioned but ultimately ineffective body. Like Churchill’s “stranded whale,” it could become a costly and embarrassing reminder of the gap between aspiration and reality.

FAQ: Understanding the Special Tribunal for Ukraine

What is the Special Tribunal for the Crime of Aggression against Ukraine?

It’s a court established to prosecute Russian leaders for the crime of aggression – the illegal invasion of Ukraine.

why is a new tribunal needed when the ICC already exists?

The ICC has limitations on prosecuting the crime of aggression, notably against non-member states like Russia.

can the tribunal arrest Vladimir Putin?

No, as a national court, it cannot arrest sitting heads of state due to sovereign immunity.

Will there be a trial even if Putin isn’t present?

The tribunal may hold trials *in absentia*, which is controversial and not recognized by all countries.

is the tribunal widely supported internationally?

no, it primarily has support from European countries, with limited backing from other regions.

What are the chances of the tribunal actually holding a trial?

The chances are uncertain due to jurisdictional limitations, lack of access to evidence, and limited international recognition.

Pros and Cons of the Special Tribunal for Ukraine

Pros:

- Addresses the “accountability gap” regarding the legality of the war itself.

- Provides a platform to document and investigate Russian aggression.

- May deter future acts of aggression by other states.

Cons:

- Limited jurisdiction and enforcement powers.

- Potential for political manipulation and selective justice.

- Risk of undermining the authority of the ICC.

- High cost with uncertain outcomes.

Will Putin Ever Face Justice? A Deep Dive into the Ukraine War crimes Tribunal

Time.news: The Special Tribunal for the Crime of Aggression against Ukraine has been launched with the enterprising goal of holding Vladimir Putin accountable for the invasion.But is it destined to become another “stranded whale,” as some fear? We spoke with Dr. Anya Sharma, an expert in international law and war crimes tribunals, to break down the complexities and potential pitfalls.

time.news: Anya, thanks for joining us. Can you start by explaining why this tribunal is being created, especially given the existence of the International Criminal Court (ICC)?

Dr. anya Sharma: Absolutely. The key issue lies in what’s being prosecuted. While the ICC has charged Putin with crimes against humanity related to the conduct of the war in Ukraine, it doesn’t address the legality of the war itself – the crime of aggression. The UN Charter prohibits wars of aggression, except in cases of self-defense or with UN Security Council authorization. Russia’s invasion fulfills neither criterion. This tribunal fills a crucial accountability gap by focusing specifically on the illegal act of aggression.

Time.news: The article highlights the comparison to the Nuremberg trials as both promising and troubling. Can you elaborate on that?

Dr. Sharma: The Nuremberg trials are the gold standard for holding leaders accountable for war crimes. They established the very principle that individuals, even heads of state, can be held responsible for their actions. The problem is logistics. Nuremberg worked because the Allied forces had custody of the defendants and access to german documentation.This tribunal faces the likelihood of neither. Putin and his inner circle are unlikely to surrender themselves, and Russia is not occupied, making access to crucial evidence extremely difficult. Proving Putin’s direct command functions in the invasion will be a monumental challenge.

Time.news: The tribunal will be based in The Hague but operate as an extension of Ukraine’s court system. What implications does this “national character” have?

Dr. Sharma: It introduces some significant limitations. As the tribunal’s own briefing papers admit,it cannot arrest sitting heads of state like Putin due to sovereign immunity. Its only real hope is to wait until he leaves office and then travels to one of the Council of Europe’s 46 member states. That’s a substantial long shot. Add to it that most of the world does not recognize the court – Africa, Asia, and South America have largely shunned it and the United States support is uncertain.

Time.news: The article also mentions the ICC’s prior indictment of Putin. How does that impact the new tribunal’s prospects?

Dr. Sharma: It creates a potential bottleneck. The tribunal can’t try Putin until the ICC’s proceedings are completed. Now, the Council of europe is considering trials in absentia – holding a trial without the defendant, which is controversial but may be the only way forward.

Time.news: Given all these limitations, many question the necessity of creating a whole new war crimes court.Why not reform the ICC instead?

Dr. Sharma: That’s a valid question. Former ICC chief prosecutor Luis Moreno Ocampo has argued that simply rewriting a few paragraphs of the ICC Statute could allow it to prosecute Russia for the crime of aggression, eliminating the need for this new tribunal. The hurdle is political will.World leaders are hesitant to expand the ICC’s powers over crimes of aggression as that could threaten too many governments. There appears to be a very selective view of international justice at work.

Time.news: The article touches on the potential for a double standard, especially regarding the U.S. and its involvement in past conflicts. Is this a valid concern?

Dr. Sharma: Absolutely. The article correctly points out that if this tribunal’s mandate weren’t limited to Russia’s actions in Ukraine,figures like former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown could face scrutiny for actions in Kosovo and Iraq. This highlights a recurring tension in international law: the conflict between principle and national self-interest.

Time.news: So,what’s your overall assessment? Is the Special Tribunal for the Crime of Aggression against Ukraine likely to succeed? What will it take?

Dr. Sharma: It’s an uphill battle, without a doubt. For this tribunal to have any real impact, it needs broader international recognition and cooperation. Ultimately, the credibility and effectiveness of any war crimes tribunal hinge on its perceived impartiality and its ability to deliver tangible justice. Whether that happens here remains to be seen.

Time.news: Thanks for your insights, Anya.

Key Takeaways for Readers:

Understanding the Accountability Gap: The tribunal aims to address a gap in international law by focusing specifically on the legality of the war in Ukraine, not just the conduct of the war.

Sovereign Immunity Limitations: Know that the tribunal cannot arrest sitting heads of state like Putin due to sovereign immunity.

The ICC’s Role: Understand that the ICC’s prior indictment of Putin could create a potential bottleneck for the new tribunal.

International Support is Critical: Be aware that the tribunal’s success hinges on broad international recognition and cooperation, which is currently limited.

consider Implications of Trials in absentia: Consider the ethical and legal implications of holding trials without the defendant present. This is controversial and not recognized by all countries.

Target keywords: Ukraine War Crimes Tribunal, Vladimir Putin, International Criminal Court, Crime of Aggression, Nuremberg trials, Accountability Gap, Sovereign Immunity, Trials in absentia*, International Law, War Crimes Prosecution, Russia, Ukraine, UN Charter, International Justice.