Scientists Discover Molecular ‘Handedness’ is Electronic, Not Just Structural

Table of Contents

A groundbreaking study from ETH Zurich reveals that the chirality of molecules – their “handedness” – isn’t solely a matter of shape, but also a dynamic electronic property, potentially revolutionizing fields from drug design to advanced sensing.

Researchers have, for the first time, measured and manipulated the movements of electrons in mirror-image molecules using ultra-fast flashes of circularly polarized light. This discovery, published in the journal Nature, challenges long-held assumptions about the fundamental building blocks of life and opens up entirely new avenues for scientific exploration.

The Enigma of Chirality

The concept of chirality – derived from the Greek word for hand – describes molecules that exist in two forms, mirror images of each other, much like left and right hands. This property is critical in biology and medicine. As one researcher explained, “Some drugs, for example, are effective only in one handed form, while the other can be ineffective or even harmful.”

Until recently, chirality was largely understood as a structural characteristic. However, growing evidence suggested this view was incomplete. “Recently, however, there has been growing evidence that the structural approach is not sufficient to fully understand chiral phenomena,” stated Professor Hans Jakob Wörner, who led the ETH Zurich team.

Unveiling Electron Dynamics

The ETH Zurich team, under the direction of Professor Wörner, went beyond observing the structure of chiral molecules to directly observe the motion of electrons within them. Their innovative approach utilized attosecond pulses – incredibly short flashes of light lasting less than a billionth of a billionth of a second – to track electron ejection and control its direction.

The team discovered that when rotating light interacts with chiral molecules, electrons are emitted preferentially in either a forward or backward direction. Remarkably, they were even able to reverse this emission pattern, a feat previously considered impossible.

“We no longer understand chirality solely as a static feature of molecular structure but also as the dynamic behaviour of electrons in chiral systems,” said Meng Han, a former postdoctoral researcher in Wörner’s group and first author of the study.

A One-of-a-Kind ‘Electron Flash Camera’

This breakthrough was made possible by a specially designed “electron flash camera” capable of delivering circularly polarized attosecond pulses. This technology is essential for capturing the incredibly rapid dynamics of electrons. By combining these pulses with a second, circularly polarized infrared beam, researchers could not only measure the speed of electron ejection but also steer the direction of their movement.

The outcome was demonstrably linked to the molecule’s chirality, the light’s rotation, and their relative phase shift, proving that electron dynamics are now both observable and controllable. Until now, chirality as a controllable electronic phenomenon had only been suspected, but lacked the technological means for experimental verification.

Implications for the Future

This research fundamentally shifts our understanding of chirality from a static property to a dynamic electronic phenomenon. The ability to observe and control electron behavior in chiral molecules has far-reaching implications. Potential applications include:

- Drug Design: More precise drug testing and the development of safer, more effective medicines.

- Molecular Electronics: Advancements in the creation of novel electronic devices.

- Spintronics: Exploring new possibilities in data storage and processing.

- Biosensors: Developing next-generation sensors with enhanced sensitivity.

The discovery also offers a fresh perspective on fundamental questions, such as why life’s molecules overwhelmingly favor one “handedness” over the other. Ultra-fast electron measurements may help identify the handedness of drug molecules with greater sensitivity, paving the way for safer and more effective medicines.

This breakthrough represents a significant leap forward in our understanding of molecular symmetry and opens doors to a new era of scientific innovation.

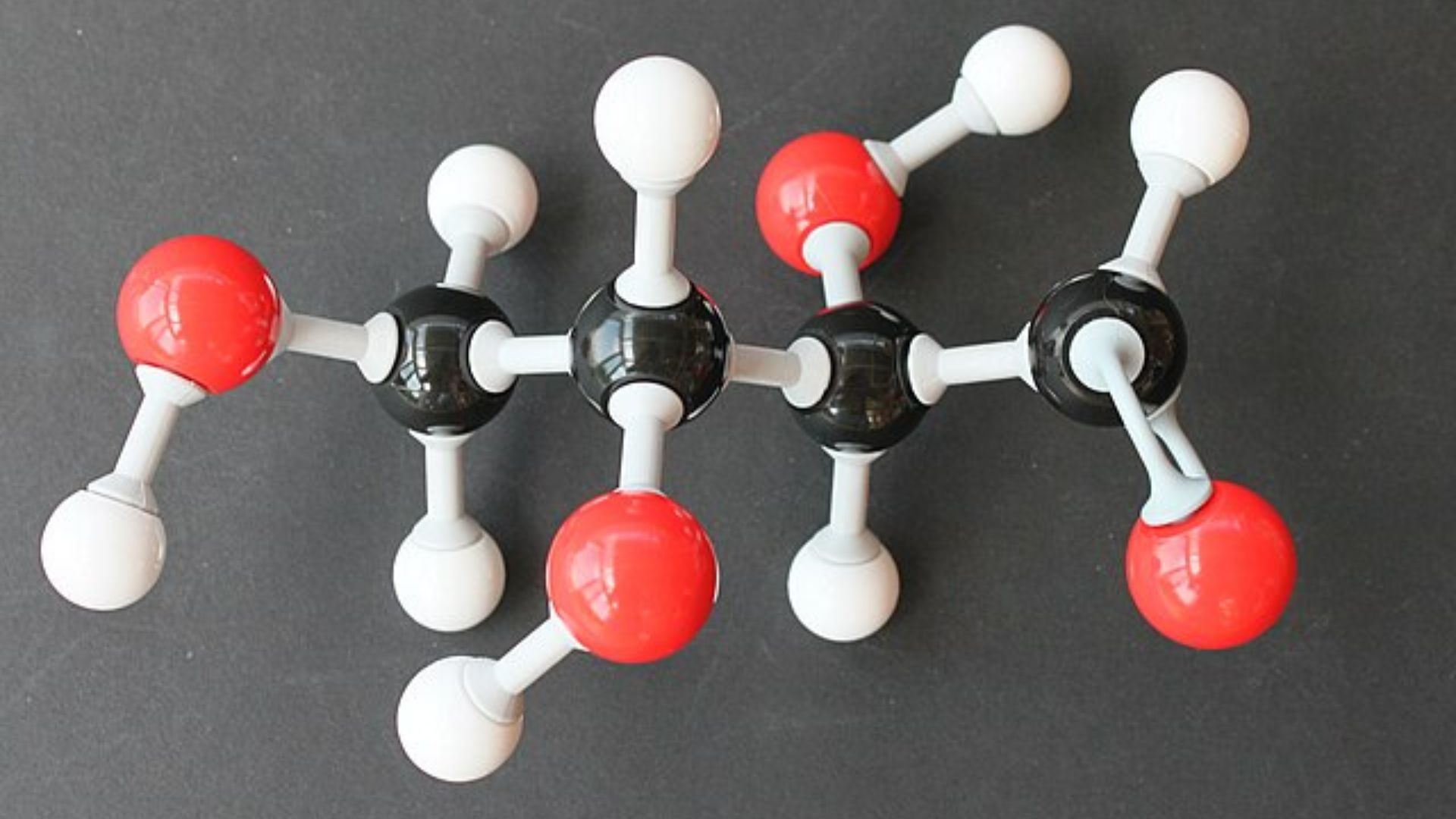

[Image of attosecond pulses and infrared pulses manipulating electron direction. Credit – Alexander Blech / FU Berlin]

The results have been published in the journal Nature.