London — Ethiopian jazz pioneer Mulatu Astatke played his final live concert last month, bringing to a close a six-decade career that reshaped the sound of music across the African continent and beyond.

A Last Bow for the Father of Ethio-Jazz

The 82-year-old musician’s November performance in London marked the end of an era, but his innovative sound will continue to inspire generations.

- Mulatu Astatke’s unique blend of Ethiopian musical traditions and jazz earned him international acclaim.

- His music gained wider recognition through its inclusion in the soundtracks of films like “Broken Flowers” and “Nickel Boys.”

- Astatke’s innovative approach, dubbed “Ethio-jazz,” combines Ethiopian pentatonic scales with jazz harmonies.

- Despite retiring from touring, Astatke remains committed to promoting Ethiopian music globally.

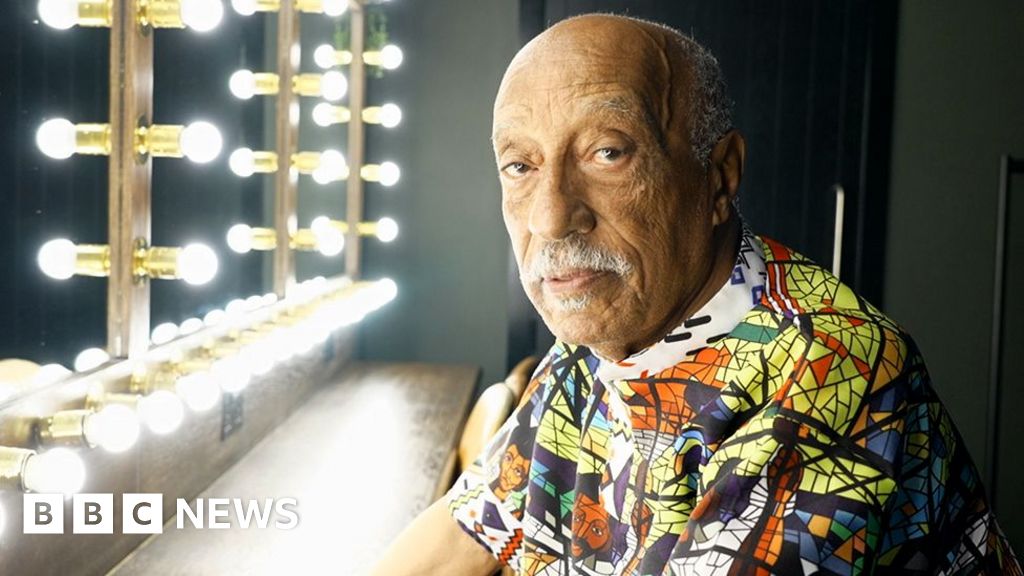

Astatke, dressed in a vibrant shirt featuring the work of Ethiopian artist Afework Tekle, walked slowly and steadily onto the stage, acknowledging the enthusiastic crowd with a wave. He moved past a set of congas to his signature instrument – the vibraphone – and began to weave his sonic magic.

What exactly *is* Ethio-jazz? It’s a captivating fusion of traditional Ethiopian melodies and scales with elements of jazz, Latin, and other global influences, creating a sound that is both deeply rooted and strikingly modern.

The first song of the evening was based on a 4th-century tune from the Ethiopian Orthodox church, a nod to his musical heritage and the Ethiopian pentatonic scale that gives his sound its distinctive flavor.

“It was a beautiful show. Really enjoyed it,” Astatke told the BBC in his gentle voice after the concert, though he remained reserved about expressing his feelings on saying goodbye to his international fans.

For U.S. musician and composer Dexter Story, the concert was “bittersweet.” “It was so vibrant and so alive. A reverent and gracious… and wonderful, wonderful energy,” he said. “I’m very saddened that we won’t have this genius… touring the world.”

Mulatu Astatke

Mulatu AstatkeBut Astatke’s influence extends far beyond the concert hall. London-based fan Juweria Dino explained, “My instinct when someone asks me to introduce them to Ethiopian music or to Ethiopian culture is to play Mulatu.”

Astatke’s music first gained wider recognition in 2005 when it was featured on the soundtrack for the Hollywood film “Broken Flowers.” More recently, his work appeared in last year’s best-picture-nominated “Nickel Boys,” further expanding his audience.

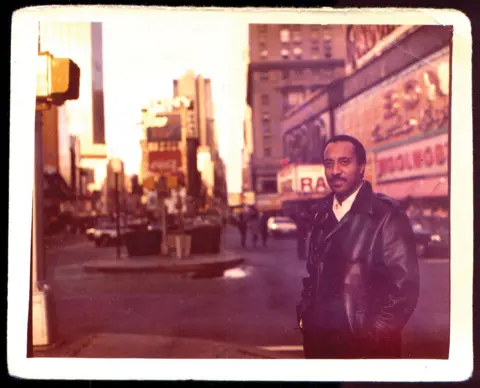

Born in Jimma, south-western Ethiopia, in 1943, Astatke was sent to Lindisfarne College in North Wales as a teenager to continue his education. Initially intending to study engineering, he was drawn to music, first learning the trumpet. Encouraged by the school’s headmaster, he eventually devoted himself to his musical gift and later attended Trinity College in London.

He recalls jamming with fellow musicians, including “[Jamaican] Joe Harriot, one of the greatest alto saxophone players,” at the Metro Club in London. He continues to hold the UK close to his heart, saying, “To me it was so really great to be back again here.”

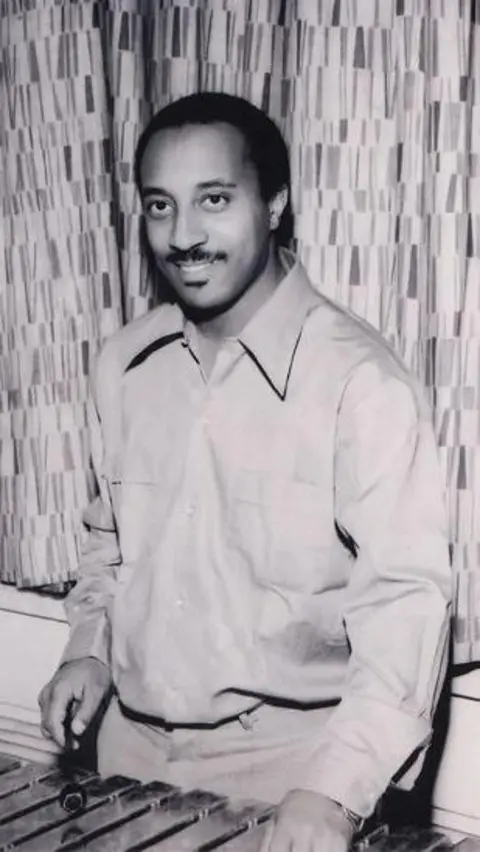

Mulatu Astatke

Mulatu AstatkeIn the 1960s, Astatke became the first African student to enroll at Berklee College of Music in Boston, where he studied vibraphone and percussion, incorporating Latin jazz into his evolving sound. However, it was upon his return to Addis Ababa in 1969 that he truly forged his unique style.

During the “Swinging Addis” years, he combined his Berklee training with Ethiopian modes, creating what he calls the “science” of Ethio-jazz. Initially met with resistance, his radical sound quickly gained traction. Even after the 1974 coup that deposed Emperor Haile Selassie, Astatke remained in Addis Ababa, continuing to create music.

Throughout his career, Astatke has drawn inspiration from traditional Ethiopian musicians, whom he refers to as “our scientists.” His tracks feature instruments like the washint (flute), kebero (drum), and the masenqo, a single-stringed fiddle that he says sounds remarkably like a cello. “But the question is, who came first? Was it the cello or the masenqo?” he pondered.

Astatke believes that African cultural contributions are often undervalued. “Africa has given so much culturally to the world. It is not being recognised as it should be recognised,” he stated.

Now, Astatke is focused on “computerising” the sounds of traditional Ethiopian instruments, aiming to broaden their reach and preserve their legacy. While his touring days may be over, his commitment to Ethiopian music remains unwavering. “It’s not the end,” he affirmed.