The shaping of characters as heroes in gothic art marked the strengthening of urban power, the weakening of religion and the beginning of social mobility.

Medieval art in Europe, from the end of the Roman Empire to the beginning of the Renaissance, is divided into several periods; One of them is Gothic art – a style that was common for about 350 years and especially at the height of the Middle Ages (from the middle of the 12th century to the end of the 15th century). This style included architectural, pictorial and sculptural elements, and was based on philosophical-religious and courtly conceptions.

Prof. Assaf Pincus, an expert in medieval art history, a senior lecturer in the Department of Art History at Tel Aviv University and an honorary professor at the University of Vienna, a researcher in culture and history through art. It focuses on Gothic sculpture and painting that took place in German-speaking areas of medieval Europe (especially between the 13th and 15th centuries). What is the question? Why were huge sculptures built in city squares in 14th and 15th century Europe? And why does their identity not match the markings that appear on them?

At the beginning of his career he dealt with the world of religious art and tried to understand the place of the imagination in it. He relates that he discovered a whole set of statues in medieval Europe that lacked identifying marks (such a mark is, for example, a white lily for the Blessed Virgin Mary and represents virginity and purity). After researching the subject he discovered that these sculptures were stripped and dressed from time to time, depending on the holiday celebrated. “When the sculptures were stripped, the viewer could project identities according to his imagination. This discovery made me delve into the world of medieval imagination, which also exists in religious art. I was interested in exploring a ‘secular’ experience in a religious world.”

Later, Prof. Pincus decided to explore the concept of violence in its modern and legal sense based on paintings and sculptures of martyrs created in churches in Germany in the 14th century. They expressed a variety of executions, such as hitting an ax on the head, nail extraction, eye poking and cooking in oil. He said, “Violence has always been expressed in art, but as an allegory and not as a representation of cruelty. The paintings and sculptures of martyrdom expressed a change in this matter and I asked myself what led to it. In a philosophical-sociological study I discovered .

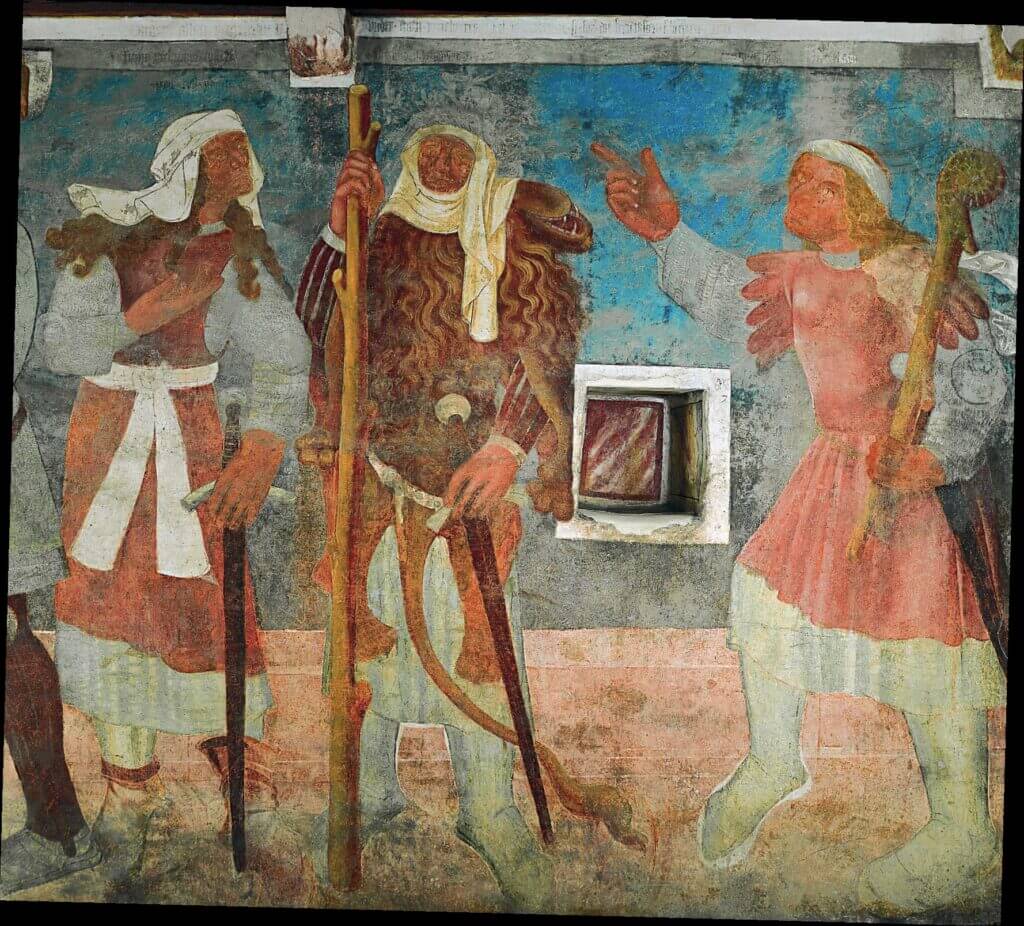

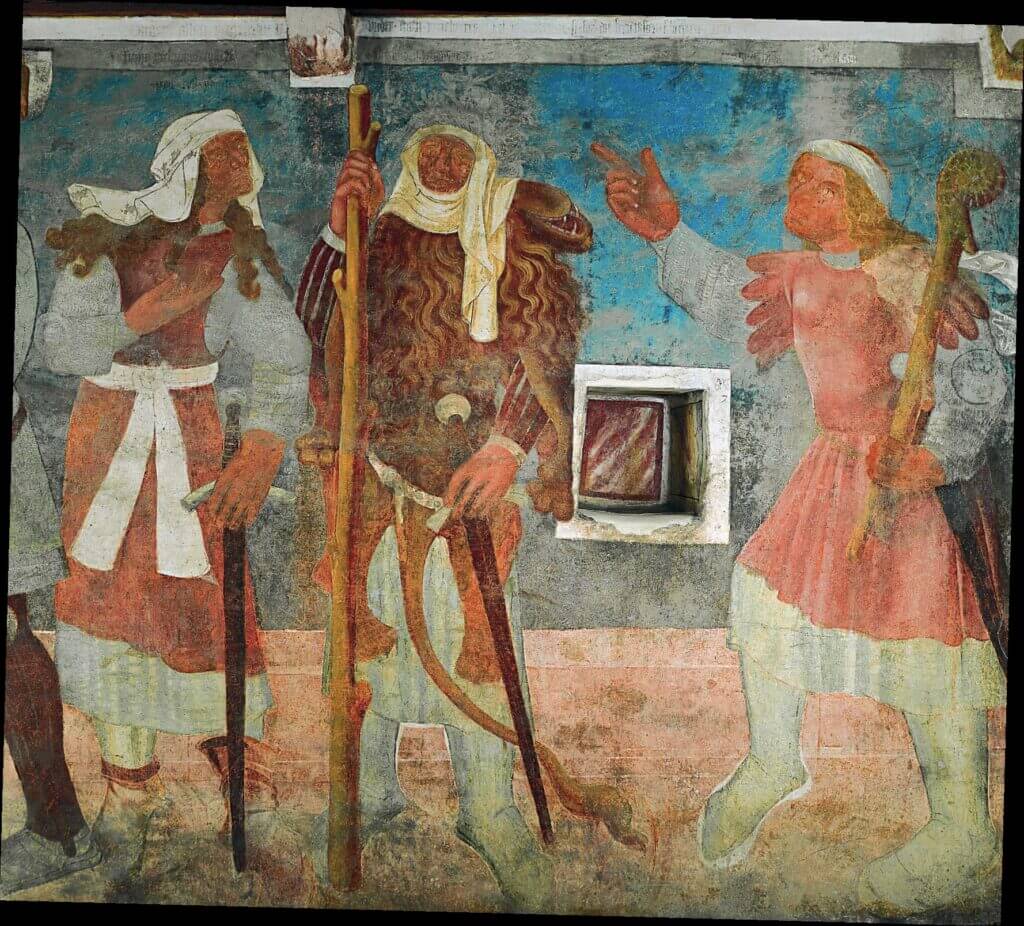

In the 14th and 15th centuries, statues about ten meters in size of heroes and heroines designed as giants and giants began to appear in city squares in Europe, in countries such as Germany, Russia and Croatia. Their symbols have been replaced by symbols that characterize giants from Norse and German mythology

In a current study by Prof. Pincus, a grant from the National Science Foundation, called “Giants in the City” and now in its third year, he found that in the 14th and 15th centuries, sculptures the size of cities in Europe, such as Germany, Russia and Croatia, began to appear. About ten meters, of heroes and heroines designed as giants and giants. Their symbols have been replaced by symbols that characterize giants from Norse and German mythology. Thus, for example, the statue of Roland / Roland from the city of Berman in Germany, the nephew of Charlemagne (one of the greatest rulers of Europe in the Middle Ages), who fell in battle against the Muslims in Spain (Battle of Ronsbo, 778); His regular insignia, such as a helmet and a horn with which he warned Carl against a military ambush, were replaced by legendary insignia – such as a hovering shield, a power belt of giants, and dwarfs and tiny animals at his feet. Prof. Pincus sought to investigate why these heroes were sculpted as giants, and why their identities did not match the markings on them, especially given the fact that they were located in such a central location in the city. He said, “In the 14th and 15th centuries, the world was Christian. If so, why did they begin to give heroes the identities of giants of pagan culture? In addition, in the Bible and mythologies, giants are a symbol of sin, excess of power, sexuality and pride.” God to wipe out giants from the face of the earth, Goliath, and the giants defeated in England by Brutus of Troy). Why, then, did they shape heroes as giants? “

To get answers to these questions Prof. Pincus scanned documentation appearing on 30 huge sculptures, in the libraries and archives of churches and cities in Europe, which include details of the circumstances of their construction and demolition. He discovered that in these centuries, urban-civilian power grew stronger, while religious power weakened. The cities liberated from church rule sought new symbols of identity and adopted the giants as a symbol of independence. Because the giants were creatures “in between,” between a wild and civilized world, between a monster and a human, between despicable and sublime, they began to symbolize states of transition and social mobility (the ability to transform from low to high class); Their symbol changed from threat to force. This is how heroes were shaped as mythological, legendary, superhuman giants. The contracts for their construction were drawn up by city councils or castle owners (especially those who climbed the social ladder, from the status of merchants to the lower aristocracy). Says Prof. Pincus: “This is how a new symbol of urbanity, independence and politics was created. I discovered that this phenomenon existed in other cultures (e.g. giant statues in China). Following this research I started writing the book ‘Global History of Giants’.”

Life itself:

Prof. Assaf Pincus, 52, married plus two (23, 20), from Herzliya. He is currently teaching art history at the International University of Venice. He previously studied confectionery in Austria and has been doing so for ten years. He later took a turn and began to study the history of art (“I have always loved art, I researched the field while still guarding what I did as a gunner, but I did not think it was possible to make a living from it”). Today in his spare time he bakes, writes novels and dances.

For an article on the website of the National Science Foundation