2024-05-01 05:43:39

The very first volume of the Leaning Church trilogy by the writer Karin Lednická from 2020 became a hit, although it was her debut. Last week, she published the expected final part of the novel chronicle of old Karviná, who fell victim to mining. The author did not disappoint. It continues to fill in the blanks of history and demystify the region, all against the backdrop of an engaging and dramatic generational story.

When you drive along the road leading from Ostrava to Karviná, before any buildings you see a bleak lunar landscape of overgrown trees, from which a mining tower juts out here and there. Somewhere between the falls crouches a small blue-gray church, leaning thoughtfully to the side. Strangely, melancholic, it stands in the middle of nowhere and most people only know about it that it is mined – a logical explanation in Ostrava. Especially from the younger generation, few people know the story of the lost city. Certainly not in full.

Karin Lednická, a native of Karvina living in Ostrava, partially changed this when, in the first part of the trilogy Šikmý kostel on the fate of one family, she described the rise and fall of this mining town between 1894 and 1961, flanked by two mining accidents. The writer soon became a bestseller with her debut, and especially in the Moravian-Silesian region, Šikmý kostel – both literary and real – became a household name. However, the novel was also dramatized the year before by the Petr Bezruč Theater in Ostrava.

Cover of the novel Leaning Church 3. | Photo: White Crow Publishing House

Readers had to wait three years for the final volume just released. It begins just after the Second World War and ends before the mining accident in 1961, which Lednická only leaves us guessing at the end, but it was brought closer in 2018 by David Ondříček Dukl’s film 61. Human tragedies, which form the basis of generational trauma, are not even in the last part of the emergency. Although the war is ending, its consequences remain, Czech-Polish relations in Těšín Silesia are still strained, the new era requires even more intensive coal mining, and the undermined old Karviná is falling apart.

The plot once again revolves around the Pospíšil family from Haví, already its third generation. The three youngest of the five siblings have the main say this time: Ženka, Wojtek and Halka. The former is still drowning in the fact that her fiance had to leave Karviná as a Czech during the war, that she could not finish her studies and married an alcoholic. Wojtek, on the other hand, looks to the future and looks forward to the beautiful tomorrows of socialism. Meanwhile, the youngest Halka blames herself for being raped by a Soviet soldier and does not know whether she is expecting a child with him or with her husband.

Beautiful 20th century

Each of the voluminous novels featured many characters with intricate destinies. From the beginning of the third part, Lednická tries to recall everything relatively non-violently and pretends the current state of affairs. The family tree on the front end also helps. Still, one would prefer to devour the engaging trilogy all at once like a series on Netflix.

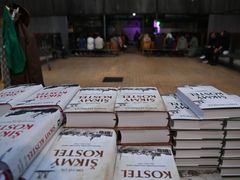

The final part of the Šikmý church was baptized in Dol Michal in Ostrava. | Photo: CTK

But it is clear why this was not possible and the volumes to the library were slowly increasing. Behind all the works of the Leaning Church, including the third one, is exhaustive research, consultations with experts on the history of everyday life and mining technology, interviews with witnesses and a search for the fates of the personalities of Karvinsk in the first half of the last century.

It is precisely in this that the great value of the writer’s work lies. He thoroughly and honestly describes the corner of history that is somehow forgotten in history classes, even in the region where it was written. Did everyone know that Těšín Silesia was occupied by Poland during the Second World War, while during the First Republic it was forcibly conquered? And that, in addition to the Germans, the Poles, who during the war were forced to apply for German nationality, were to be expelled from Karvinsko after 1945?

The last part of the Leaning Church has a well-constructed plot structure. The story is engaging and suspenseful, although often predictable. Not in a bad way though. It’s more like watching a good series and correctly guessing what will happen next, with just enough advance notice to keep you entertained. In addition, anyone who has a basic knowledge of the history of the “beautiful 20th century” must have guessed what tragedy will affect the life of the mining family.

At the same time, a certain predictability corresponds to the spirit of the described time. Although the historical events in the background are dramatic, life paths and gender roles are fixed – women give birth to children, men dig coal and talk about politics. The destinies of all generations of protagonists unfold in small variations along the trajectory of birth-shaft-marriage-children-death. Most of the characters cling to this one of life’s few certainties. “A person should live where he was born,” says one of the heroines, Barka, who is looking forward to dying in the bed where she slept next to her husband for 40 years and gave birth to five children in it.

This rigidity serves not only as an image of the time, but also as a mirror of today. A large part of people probably prefers the current multiplicity of choices to the givens of the time, but today academics have also described that their excess can lead to paralysis and feelings of inadequacy, especially among young people. The complexity of today’s world is also psychologically demanding. With Lednická’s novels, one can get a little carried away and dream about a simple life next to a “good man” spent in one bed instead of moving after renting – and also realize that it’s just stupid romanticizing and that one wouldn’t want to put on shoes only one of her characters.

Karin Lednická won the Prize of the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes for the Leaning Church in 2021. She received it for her contribution to the reflection of modern history. | Photo: CTK

One Lednická for the Sudetenland, please

The weakness of Lednická’s narration is a certain clumsiness in the frequent switching between the past and the one being described. The writer several times previews the scene, then returns to the past to explain it, and then returns to the initial image. The awkward donkey bridge finally closes with a twist like “and that’s why he’s sitting here now”. Coordinating so many storylines over 600+ pages is of course no easy feat and is an admirable feat in itself. But when the reader encounters the same principle several times in each chapter, it starts to feel boring. In addition, the author proceeded similarly in the previous two works.

It’s also a shame that the story leaves no room for imagination apart from the two interlude chapters. Everything is said literally, even what one would have guessed on their own. It is not necessary to write literally that little Juliet inherited intelligence from her mother Harvest – it is clear from the story. Lednická tries to explain every movement of the characters and repeats many things from the perspective of several heroes without it serving a special purpose in the story. The book thus swelled by several tens of pages more than was necessary. On the other hand, this straightforwardness makes the trilogy widely accessible and probably thanks to this it has spread to so many readers.

Another reason why the Lednické chronicle has gained so many fans is its great storytelling talent. He is exceptionally able to draw you into the story, and the reader cannot tear himself away from the story of several generations of one family. The characters are faithfully modeled, so you feel as if you know them, and you shudder with horror at what other tragedy will befall the hero.

Depicting how difficult life in the Karvina mining colony could be, however, is not an end in itself with the aim of arousing emotions. It explains why people in Ostrava are still the way they are today – to some they may seem too direct, matter-of-fact or harsh. One would like to say hardening, although many people today will probably admit that it is not the best strategy to cope with life’s difficulties.

But the heroes of the Leaning Church chose her – it was probably the only way to survive. And as we know today, we can also be traumatized by what did not happen directly to us, but to our ancestors. “Of all the options, Mom always chose suffering rather than trying to find another way,” says one of the characters in the final novel. That sentence will resonate with Lec people from Northern Moravia and elsewhere.

But Lednická’s greatest contribution is that it returns history to an uprooted and stigmatized region. Let it be a proof of how the once desolate surroundings of the Church of St. Peter of Alcantara, or Leaning Church, came to life. Today, especially on weekends and holidays, people from the wider area stop there and walk in the places where the city once stood. Gradually, there were also signs showing where the heroes of the novels went and where an important building stood.

At the same time, the author resolutely fights against the stereotypes that are associated with the coal region and which flow not only from the ethos of the former totalitarian construction on coal foundations described in the book, but also from contemporary pragocentrism. Karin Lednická, on the other hand, sensitively describes the Háví craft, which is so closely connected with the region, as hard and dangerous work, but full of honest people with a sense of “partying”. Perhaps northern Bohemia would also need its own Lednická, a region perhaps even more secluded and invisible than the Moravian-Silesian one.

The mining disaster and the painful division: It was impossible to write briefly, says Karin Lednická (February 19, 2021)

Těšín is really a region on the fringes of interest, the happy crasher from the normalization jingle of Televních noviny is only a fraction of reality, the writer thinks. | Video: Martin Veselovsky